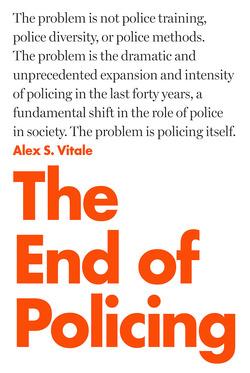

The End of Policing

By Alex S. Vitale

Verso, 226 pages

Harcover: $26.95 (40% off if ordered by Oct. 31, 2017)

October 10, 2017

ISBN: 978 7847 82894

Do we need the police?

Brooklyn College sociologist Alex S. Vitale poses that question vividly in his The End of Policing: Are the police guarantors of social peace or its disruptors? Is the force’s mandate to serve the public equally and fairly, or to act as social-control agents, protecting property and its few owners at the expense of the many?

Vitale traces the origins of the current push for policing as the universal solution for social ills to the 1980s popularization of the conservative nostrum “broken windows policing.” It promoted “zero tolerance” for surface manifestations of disorder no matter how minor, arguing that if that disorder were allowed to exist, it would inevitably metastasize into serious crime.

He argues that policing is the wrong solution for many issues, particularly those where something’s illegality itself — alcohol in the 1920s, gambling and marijuana — is what makes it a problem. Drug addiction, he insists, is not a criminal-justice issue: As with sex work, it is the prohibition that makes it criminal and allows victimization through exploitation. Even gang violence, he claims, is largely a response to police provocations against black and brown youth. Border policing, when not just deadly, is a dead end. It can’t stop the flow of migrants, not when free trade destroyed local economies in Central America while U.S. agribusiness requires a seasonal workforce, but won’t pay living wages to Americans.

Even when police practices are based on good intentions, Vitale argues, cops often work with populations better served by specialists, especially those like drug counselors and youth social workers who have emerged from the communities affected by those problems. The law creates a Catch-22 for social services such as drug treatment: Even where special programs exist for treating and housing addicts, individuals referred by the criminal-justice system get to jump the line and displace those with similar needs who aren’t facing criminal charges. In many cases, people not facing charges aren’t eligible for services.

In the case of the mentally ill, Vitale notes how such seemingly salutary innovations as “crisis response teams, specialized courts and improved training can reduce the impact of the criminal system on the mentally ill and on the criminal-justice system, but these are not replacements for a rational, functioning mental-health system.”

The punitive treatment of sordid-looking and often annoying homeless such as aggressive panhandlers may soothe public sensibilities, but has no impact on the overall homeless situation. Without a housing policy that creates stable, long-term residences, chasing the homeless away and eradicating squatter camps is not just ineffective, but cruel.

In a humane and relatively cooperative society, there would be few areas that require police intervention. Vitale’s point, then, is not to eliminate the police per se, but to collapse the need for police to an irreducible minimum.

In an otherwise comprehensive discussion of political repression, Vitale could have spent more time on police repression of workers’ struggles, which he treats as political repression of the left in just one omnibus chapter. He’s not wrong, but treating these as purely political and not also fundamentally economic attacks slights the broader systemic aspect of police intervention against strikes and job actions. Labor history is replete with those attacks.

He also doesn’t acknowledge the reactionary role played by police unions. In New York, the Patrolmen’s Benevolent Association, along with the detectives’ and sergeants’ unions, do more than defend their members: They actively lobby for retrograde social legislation both in City Hall and in Albany. Opposition, largely from officers of color, does occur, but more often over issues like discrimination within the force than over community concerns.

Vitale presents a dialectic in which police intervention becomes provocation in too many situations, causing oppressed people to fight back sometimes but not often enough in ways that build the community and a movement, which in turn only exacerbates police and state repression. Even where police try a soft approach, as with community policing or the use of non-punitive civil rather than criminal courts, the threat of arrest and criminalizing is omnipresent. For addicts, treatment and housing is never long term. In the absence of such necessary arrangements, it is no wonder that some despairing elements in affected communities ironically demand more police protection even as others fight for better-grounded services.

Any ameliorating influences police could provide would better be served, as Vitale gives examples throughout, in well-funded social programs framed with the advice and consent of local people. Above all, jobs or an adequate income flow would be the death knell of urban and rural poverty, the real cause of crime and delinquency, and Vitale says as much. But that requires radical social change, Vitale’s overall point, though he doesn’t press it home. The book is only implicitly an anti-capitalist critique. To do more would mean writing another book.

Short of the average cop having the wisdom of a Talmudic scholar and the patience of a sacristan, nothing can overcome the objective reality of ineffective training, dangerous situations and an ethos that stresses suppressing criminals over community-building and systemic prevention of crime, and often doesn’t discourage thuggery. The end of policing as we know it can’t come too soon.

Much of Vitale’s empirical evidence parallels that in the excellent Truthout collection Who Do You Serve, Who Do You Protect? and he acknowledges an intellectual debt to Michelle Alexander’s The New Jim Crow. Those are both key works in understanding police and racial repression. But Vitale’s amassing of trenchant facts into an enticing intellectual framework makes The End of Policinga must-read for anyone interesting in waging and winning the fight for economic and social justice.

Author Alex S. Vitale is professor of Sociology and coordinator of the Policing and Social Justice Project at Brooklyn College. His writings about policing have appeared in The New York Times, Daily News, USA Today, The Nation and Vice News. He has served on the staff of the San Francisco Coalition on Homelessness from 1990 to 1993, heading up its work on developing and preserving health care and social services programs, and defending the civil rights of people living on the streets and in shelters. Vitale is also an elected officer in his faculty union, the Professional Staff Congress-CUNY, an affiliate of the American Federation of Teachers.

[Essayist Michael Hirsch is a New York City-based labor and political writer, a member of the editorial boards of New Politics and Democratic Left, and a Portside moderator..]

The Indypendent is a Brooklyn , N.Y.-based progressive monthly, distributed free in New York City and on-line. Information on subscriptions for the print edition or joining its mailing list are available at https://indypendent.org/.

Spread the word