On February 26, 1928, a headline in the New York Times announced, “MARCH OF THE MACHINE MAKES IDLE HANDS,” with the subhead: “Prevalence of Unemployment With Greatly Increased Industrial Output Points to the Influence of Labor-Saving Devices as an Underlying Cause.”

What these alarming words referred to was the abundance of goods being produced in the roaring plants, mills and farm fields of 1920s America. According to a variety of statistics cited and charted by the Times, what Americans could now make was beginning to outstrip what they could consume, to the point of diminishing employment.

“More and more the finger of suspicion points to the machine,” the Times reporter, Evan Clark, claimed. “It begins to look as if machines had come into conflict with men—as if the onward march of machines into every corner of our industrial life had driven men out of the factory and into the ranks of the unemployed.”

Clark’s contention, it turned out, was overstated—unemployment, at the time, remained at only 4.2 percent nationwide. But the fear that “the machines”—automation—might possibly be detrimental to American life was something relatively new, and very real. Since America’s early days, there had been flashes of concern, but nothing like the disruptions caused by new technology that set off full-blown labor wars in England and France during the first convulsions of the Industrial Revolution. For one thing, most people in antebellum America worked for themselves, as farmers or housewives, artisans or professionals. New technology usually meant labor-saving devices, from the mechanical reaper to the dishwashing machine. Fears of white, working-class people centered more on being displaced by immigrants and African Americans, or the country’s rickety financial and banking systems. The imposing new factories that initially sprang up seemed to prove that the machines only made jobs.

By the end of the 1920s, however, that belief had begun to wear thin, and the machine seemed a menace. Today, we tend to think of our trepidation about automation as a relatively recent phenomenon, one that reflects TheMatrix- and Watson on “Jeopardy!”—fears of artificial intelligence overtaking our own. But in fact, we began fearing much more primitive devices decades ago, and that fear reliably resurfaced when our economy faltered. Our present anxiety about robots taking human jobs might well prove to be warranted—but it is not novel.

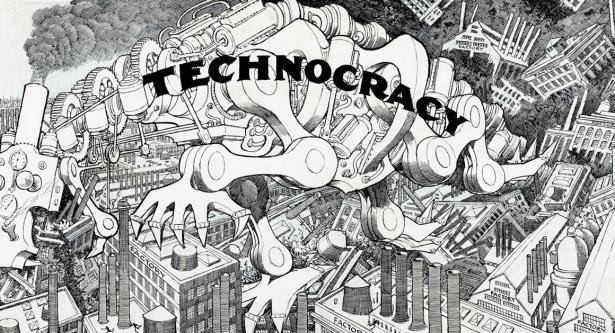

With the onset of the Great Depression, the widespread fear about technology was that it would lead to “overproduction,” which was seen by many at the time as the major cause of our worst economic meltdown. President Herbert Hoover received a hysterical letter from the mayor of Palo Alto—his adopted hometown and later, of course, the hub of Silicon Valley—warning that a “Frankenstein monster” of industrial technology was “devouring our civilization.” In 1932-1933, there was widespread excitement about an eccentric new, socio-political movement advocating the reorganization of society as a “Technocracy.” Technocrats, in the words of historian Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr., believed that “the inexorable increase of productivity, far outstripping opportunities for employment or investment, must mean permanent and growing unemployment, and permanent and growing debt, until capitalism itself collapsed under the double load.” The only solution, said the technocrats, was to drop our outdated and supposedly irrational “pricing system” for goods in favor of a new financial system that would tie everything to the amount of energy needed to produce goods, and redistribute money based on “ergs” and “joules” and other measures of literal power.

Technocracy proved to be a passing fad. But one of its central contentions—that machines made overproduction inevitable—was widely believed to be the underlying cause of the Depression. Even Franklin Roosevelt, during his 1932 presidential campaign, voiced his belief that the overproduction of the machines was driving unemployment, insisting, “Our industrial plant is built; the problem just now is whether under existing conditions it is not overbuilt.”

Once in office, FDR discovered that, in fact, our industrial plant was far from “finished,” and set about providing the infrastructure—and the buying power—to make building many more factories possible. World War II provided an object lesson in just how many workers America’s modern, industrialized economy could absorb. The country’s amazing wartime production—and the even more amazing postwar boom that followed—dimmed economic anxieties, and increased our confidence that we could handle whatever inventions might come. “If men have the talent to invent machines that put men out of work, they have the talent to put those men back to work,” President Kennedy proclaimed in 1962.

Not everyone was so sure. When, the Ford Motor Company moved its engine block production to a largely automated factory in Brook Park, Ohio, in 1949—a plant where automatic machine tools cut manpower by 90 percent—MIT professor Norbert Wiener, the father of cybernetics, warned that, “in the hands of the present industrial set-up, the unemployment produced by such plants can only be disastrous.” Some United Auto Workers activists wanted to respond by demanding a 30-hour week at 40-hour wages. But Walter Reuther, the visionary head of the UAW, remained sanguine, using his union’s power to keep his laid-off men employed elsewhere in the vast Ford empire, and their wage structure intact. “Nothing could be more wicked or foolish,” than to resist the mechanization of the auto line,” Reuther said in the mid-fifties. “You can’t stop technological progress, and it would be silly to try to do it if you could.”

Anxieties revived when a wholly new type of machine, one that didn’t replace just assembly-line brawn but human brains, began to enter the workplace. This was the computer, and while its earliest practical manifestations were a far cry from the incredible entities we work with today, the advent of the “thinking machine” caused an immediate uproar, everywhere it popped up in the workaday world.

In “When the Computer Takes Over the Office,” a 1960 article for the Harvard Business Review, the noted sociologist Ida Russakoff Hoos delineated just what the computer could do to roil the workplace. After a three-year study of 19 firms that adopted electronic data processing, she reported that executives and workers alike were left disoriented (or unemployed), and the new computer jobs created by these new machines were grim: New key-punch operators felt they were “chained to the machine,” in “a dead-end occupation with no promotional opportunities,” Hoos wrote. (Their plight was more widely publicized in the movie Desk Set, the 1957 Katharine Hepburn-Spencer Tracy romantic comedy, in which an enormous “EMERAC” computer is installed in the New York Public Library’s legendary reference library, sowing similar resentments and fears among the librarians.)

Even more disorienting developments were already on their way: the melding of the computer brain with—literally—a mechanical arm. By 1954, George Charles Devol Jr. had invented the “Unimate”—for “Universal Automation”—robot. Little more than a hydraulic arm attached to two boxes, one of which contained its memory, Unimate didn’t much look like what we had come to envision as a robot. But it would change the world. Going on line first in 1961, within eight years Unimate robots were running General Motors’ Lordstown, Ohio, plant, the most automated auto factory in the world, turning out 110 cars an hour. A Unimate model even made an appearance on “The Tonight Show,” where it delighted Johnny Carson by placing a golf ball in a cup, opening and pouring a beer, waving a bandleader’s baton and grabbing and swinging around an accordion.

Those parts of America that worked for a living were less amused. In 1964, a group of futurists, technology scholars, social activists and academics, calling themselves the Ad Hoc Committee on the Triple Revolution, sent an open letter to President Lyndon Johnson, predicting that “the cybernation revolution” would produce fantastic increases in productivity, beyond our ability to possibly consume them, and at the same time leave much of the country unemployed, “a separate nation of the poor, the unskilled, the jobless.”

The committee called for the federal government to meet this threat with massive infrastructure projects, affordable housing, cheap public transportation and electrical power, income redistribution, the unionization of the unemployed—and a universal income. Johnson’s own secretary of labor, W. Willard Wirtz, concurred that the new, thinking machines now had “skills equivalent to a high school diploma,” and that they would soon take over the service industry. Other social scientists, deciding that there would just be no real need to work much, began to worry about the emotional and psychological impact of enforced idleness.

No less than Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., listing the goals of the civil rights movement for 1964, cited “monstrous automation” as one of the leading obstacles to African Americans achieving equal economic opportunity. And he did so with good reason: Under prevailing, “last hired, first fired” traditions in many workplaces, black workers were especially vulnerable to layoffs that might be wrought by the new, computerized machines.

Johnson used these burgeoning concerns to do more or less what he had planned to do anyway: continue in the New Deal tradition of liberal optimism with an enhanced program of education, job training, human rights, more massive infrastructure programs, and provisions for the sick, the elderly and the infirm. This included much of the program advocated by the calamity howlers of the Triple Revolution, but ignored their demand for a guaranteed universal income. No doubt, LBJ understood that any such proposal would have been widely regarded as a call for a massive dole. Instead, the Great Society, he was careful to reassure listeners in the original speech laying out this vision, “is a place where leisure is a welcome chance to build and reflect, not a feared cause of boredom and restlessness. … ost of all, the Great Society is not a safe harbor, a resting place, a final objective, a finished work.”

As general prosperity continued over most of the next 15 years, Kennedy and Johnson—and most of the world’s economists—appeared to have been vindicated. America would always find ways to put people to work, and technology, ultimately, would always create more (and better) jobs than it eliminated.

Or will it?

In the past decade, as our economy collapsed, then languished, and as computers and robots reached whole new levels of ability, fears about just what we will all do in the very near future have returned with a vengeance, producing a flurry of books, articles and speeches.

Futurist Martin Ford argued in his 2015 book, Rise of the Robots, that pretty much everything the Committee on the Triple Revolution argued would happen is in fact coming true, albeit in slow motion. Since the late 1970s, he points out, real wages have stagnated, gaps in both income and opportunity have become chasms, more people are unemployed or out of the workforce altogether, and our society is becoming fatally polarized. In an article in the Economist last year, Michael Morgenstern related the chilling information that computers can now outperform human radiologists—it’s not even close. Driving, in one capacity or another, is now the leading occupation of men in the United States. With the self-driving car—and, more importantly, truck—just around the corner, we’re talking about a massive displacement for a part of the population that already feels itself to be ill-used and overlooked.

Our conflicted feelings persist. Many economic analysts still argue that this wave of technology, like all previous ones, will add many more new jobs, by both creating vocations we can’t yet envision and “reallocating” work within existing professions. The New York Times recently reported on how truck drivers are being trained to guide numerous, long-distance rigs electronically, from inside the safety and comfort of an office, or to take them from the highway to their final destination. Someone is going to need to go get all those self-driving vehicles when they break down, and someone is going to have to rebuild all of our roads so that the next generation of electric cars can recharge themselves as they drive. Or maybe it just won’t be necessary to work as long and hard as we all seem to do today.

Whatever we decide to do, it is next to impossible to imagine government stepping up and responding to economic change with the sorts of massive public works projects, social work programs and education subsidies that marked the New Deal and the Great Society. Neither Donald Trump’s promise to rebuild protectionist trade walls nor the left’s tepid offer of improving education are likely to stop robots from taking human jobs en masse—to say nothing of the lack of political will in Washington generally. In that sense, even while our anxieties about automation might be old-fangled, we may indeed be entering a new frontier.

[Kevin Baker is author, most recently, of America the Ingenious: How a Nation of Dreamers, Immigrants, and Tinkerers Changed the World. Lara Jones contributed research.]

Spread the word