When America Had an Open Prison – the Story of Kenyon Scudder and His 'Prison Without Walls'

In a country with mass incarceration, horrific prison conditions and a penal system suffused with racism, some American prison reform activists wistfully look to Scandinavian institutions as beacons of humane prisons.

Many Scandinavian countries even have open prisons – minimum security institutions that rely less on force and more on trust. Some don’t even have a locked perimeter, and they emphasize rehabilitation and preparation for a return to society.

Back in the U.S., this might seem like an unattainable ideal.

But in California, nearly 80 years ago, there was an open prison.

As part of our work as human rights researchers who specialize in prisons, we were studying the United Nations resolution on open prisons, which was adopted in 1955 in Geneva. In a meeting prior to this resolution, penal experts discussed open prisons in the U.S., with the American delegate calling them “the contribution of this generation” to modern prison management.

Led by a prison reformer named Kenyon Scudder, the California Institution for Men was one of these open prisons. Scudder made the dignified treatment of its prisoners a cornerstone of his approach.

A different kind of prison

Built in 1941 in Chino, California, the California Institution for Men was founded as an experiment in progressive penal reform.

At the time, California’s maximum security institutions in San Quentin and Folsom were, as one newspaper put it, “powder kegs ready to explode.” Violence was rampant, particularly between guards and convicts, and California was considered to have one of the most oppressive penal systems in the nation.

To alleviate the draconian and overcrowded conditions at San Quentin and Folsom, in 1935 the California state legislature decided to build a new prison.

Kenyon J. Scudder, a veteran penologist who had a raft of ideas for how to change a prison system he viewed as archaic and inhumane, was hired to head Chino.

Kenyon Scudder speaks with an inmate working for the California Institution for Men’s farm program. California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation

Scudder accepted his appointment with conditions: He wanted to be granted the power to select and train the staff, and the autonomy to dictate how much freedom the prisoners could have.

The California Institution for Men’s first class included 34 inmates – some who had been previously convicted for violent offenses, along with others who had committed minor offenses.

Those first inmates entered an entirely different kind of prison. The California Institution for Men didn’t use terms like “warden” or “guards.” There was the “superintendent” – Scudder – and his “supervisors,” the vast majority of whom were college educated.

In fact, Scudder intentionally avoided hiring supervisors who had previously worked in prisons: He didn’t want staff members with punitive mindsets. Instead of relying on batons and guns, he trained this new staff in judo for self-defense. Weapons were reserved for absolute emergencies, and Scudder emphasized the development of conflict resolution skills.

Those being held wouldn’t have their identities reduced to a number. They could choose their own clothing and which jobs to do and what to study. Their cells had locks, but accounts indicate they weren’t used. The original plans for the prison called for a 25-foot perimeter wall with eight gun towers. Scudder put a halt to this; instead, he convinced the Board of Prison Directors to erect only a five-strand barbed wire livestock fence.

Scudder encouraged family members to regularly visit, allowed inmates to have picnics on the grounds and even permitted some physical contact.

He also refused to segregate anyone along racial lines, an unusual policy at the time.

‘Prisoners are people’

Informing Scudder’s approach was his deeply held conviction that prisons should treat people with dignity. He believed that doing so would be the best way to encourage inmates, once they gained their freedom, to be productive members of society. And he argued that it would ultimately save the state money by reducing recidivism.

Scudder believed that the worst thing you did shouldn’t define you. He wrote about the hypocrisy of the moral superiority expressed by people outside of prisons; most people who commit crimes, he noted, aren’t caught; it’s “mainly the little fellows.”

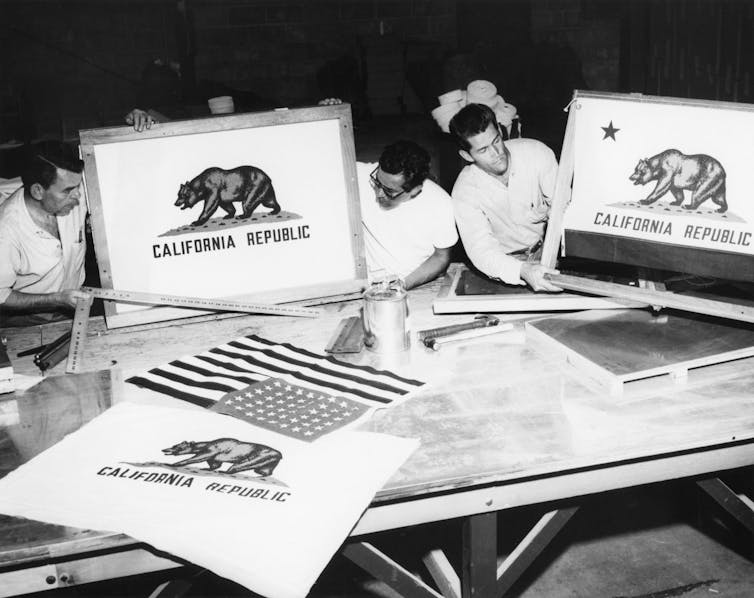

In this 1958 photograph, inmates work on a silk screen project at the California Institution for Men’s clothing factory. California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation

In its early years, the California Institution for Men received positive press. In 1952, Scudder published a memoir, “Prisoners are People,” that told the story of the prison and outlined his prison philosophy. In 1955, the book was adapted into a film titled “Unchained,” which today can be seen only on The Internet Archive. (According to a Harvard University librarian, the DVD is held by only one library in the world.)

The movie, a dramatization of life in the Chino prison, depicts friendships forged across racial lines and built on trust and interdependence. Inmates, well aware of the alternatives, feel a collective sense of responsibility for the prison’s success.

The movie ends with the main character nearly climbing the prison fence to freedom. But the man chooses to stay after his friend confronts him. If he leaves, he realizes he’ll risk the future of this rare prison.

The film is sappy, moralistic and likely hagiographic. But the ideas at its heart reflect Scudder’s ideals.

The dream falls apart

The California Institution for Men still exists today. But its original mission no longer does.

Not everyone was on board with Scudder’s philosophy. The state’s prisons had long been patronage mills and landing spots for political appointees. Scudder put a stop to this custom, which put him under heightened scrutiny and criticism from the state’s politicians.

By the time Scudder died in 1977, the institution had morphed into a larger, more traditional correctional complex with three maximum security facilities. The pressure of overcrowding and rising incarceration rates spurred this transformation. Periodic escapes led to more political pressure to tighten security. Then, in 1983, an escapee named Kevin Cooper was convicted of murdering four people, though his conviction remains controversial and there have been calls to grant him clemency as recently as 2018.

Today, it has 3,766 inmates, which is 25% over capacity.

Yet for a brief period of time, it seemed that other prisons around the world would follow Chino’s lead.

In the early 1950s, prison experts at the International Penal and Penitentiary Congress agreed that open prisons should eventually replace traditional cell-based prisons for nearly all types of inmates. In 1955, a United Nations resolution adopted at the First Congress on the Prevention of Crime and the Treatment of Offenders recommended “the extension of the open system to the largest possible number of prisoners.”

In the U.S., after years of punitive policies and laws, the pendulum is swinging toward compassion. Even under a law-and-order president like Trump, modest reforms have been made. The public’s appetite for the harshest forms of punishment is waning, and criminal justice reform occupies a rare bipartisan policy space. Even arguments for prison abolition are gaining traction, along with a skepticism of piecemeal reforms that may reinforce abusive prison systems. Other high-profile politicians are calling for greater investment in policies that promote racial and socioeconomic equality, rather than relying on policing and prisons to control crime.

Though Scudder’s vision was realized for only a relatively brief window of time, the California Institution for Men is an important reminder that the U.S. practiced in the past what prison reformers admire as humanistic punishment elsewhere.

[ Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter. ]![]()

Emily Nagisa Keehn, Associate Director, Human Rights Program, Harvard Law School, Harvard University and Dana Walters, Program and Communications Coordinator, Human Rights Program at Harvard Law School, Harvard University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Spread the word