There’s a widespread recognition on the US and European left that our democratic institutions are failing. From Bernie Sanders’s campaign for a political revolution against the structures of US oligarchy to Rebecca Long-Bailey’s pitch to abolish the UK House of Lords and deal the British state a “seismic shock,” prominent democratic socialists are well aware that the movement for a more just social order is inextricable from the drive to democratize our political systems.

The problems are familiar: corporate and elite influence over decision-making and legislation, unchecked executive power, distant and unaccountable representatives. Our political systems alienate those subject to its decisions and threaten to stymie any socialist government that comes to power. Less clear, however, is what concrete changes might begin to address these problems.

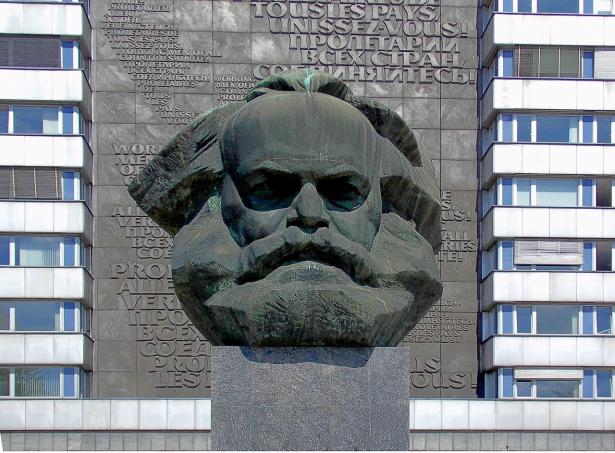

One fruitful source of ideas is the political and constitutional writing of Karl Marx. That might come as a surprise, considering Marx is normally thought of as a purely economic thinker, with little to say about the design of constitutions and political institutions.

And it’s true that Marx never produced a fully fleshed out constitutional theory of his own. But the famed socialist was a committed democrat whose writings contain a nuanced critique of liberal constitutionalism and representative government, as well as a sketch of what popular institutions should replace it.

Many of these ideas — the necessity of holding representatives accountable, the importance of legislative supremacy over the executive, and the need for a broader popular transformation of the state’s organs, especially the civil service — were inspired by Marx’s experience of the Paris Commune, the working-class uprising that briefly controlled the city from March to May 1871. They were also in line with, and partly drawn from, an older radical tradition of political thought that encompassed British Chartists, French democrats, and US Anti-Federalists (a tradition that Karma Nabulsi, Stuart White, and I explore in our forthcoming book, Radical Republicanism).

It would be wrong to treat Marx’s ideas as a blueprint to rigidly follow. His writings do not provide nearly enough detail for that (unsurprising for someone opposed to writing “recipes for the cookshops of the future”), and no thinker should be treated as a fixed repository of truth. But as we think about how to democratize our political institutions, Marx’s writing is an important resource from which to draw.

Crucially, it also provides us an opportunity to remind ourselves of the centrality of democracy to socialism. Not only is democracy an essential precondition for building socialism, our motivation to democratize the political system springs from the same source as our desire to democratize the economy: that people should have control over the structures and forces that shape their lives.

“Universal Suffrage Would Serve the People”

Marx believed that universal suffrage was an essential prerequisite for socialism. At his most optimistic he thought that “ts inevitable result . . . is the political supremacy of the working class.”

But he worried that representative government was undermining the emancipatory potential of the vote, granting elected officials large discretion over how to vote and act in legislative bodies. Regular elections provide voters with important sanctioning power (they can choose to throw the bums out), but representatives are not formally tied to the wishes of the electorate. Marx believed that this created a class of unaccountable officials who were more likely to represent their own elite interests than those of their constituents.

He endorsed several mechanisms to narrow the gap between representatives and the represented — foremost among them, the recall. This would give citizens the power to immediately sanction representatives rather than waiting years for the next election. Marx joked that while employers trusted in their “individual suffrage” to “put the right man in the right place, and, if they for once make a mistake, to redress it promptly,” those same employers were horrified at the idea that universal suffrage might imply a similar power for voters.

Marx also supported “imperative mandates,” where constituents give representatives legally binding instructions — affording citizens direct input into the legislative process and prohibiting elected officials from reneging on campaign promises. Finally, Marx was critical of lengthy parliamentary terms and advocated much more frequent elections. Commenting on the Chartists’ demand for annual elections, Marx noted that it was one of the “conditions without which Universal Suffrage would be illusory for the working class.”

Together, Marx argued, these measures would transform representative government: “nstead of deciding once in three or six years which member of the ruling class was to misrepresent the people in Parliament, universal suffrage . . . serve the people.”

In contemporary politics, the Left has not always been as successful as the Right in galvanizing anger against distant and unaccountable representatives. Boris Johnson and his media cronies effectively channeled Leave voter outrage at the UK parliament’s role in the Brexit negotiations into a “people versus parliament” narrative. In Italy, the right-populist Five Star Movement achieved significant initial success through its attack on corrupt politicians and its promise to implement an imperative mandate between its representatives and members. That has made it easy for liberals to dismiss criticisms of representative government and countermeasures like the imperative mandate as objectionably populist.

But it would be a mistake for the Left to cede this ground to the Right. Marx’s recommendations may not be the exact institutional mix we settle on, but they should form part of our constitutional arsenal when considering how to make representatives accountable and give citizens a real say in their democracy.

A Critic of the Executive

Despite Marx’s misgivings about representative democracy, he viewed the legislature as central to democratic politics. He praised the Paris Commune for assigning ministerial-like posts to members of the commune council itself, rather than creating a president and cabinet separate from the legislature.

For Marx, excessive executive power was even more dangerous than distant representatives. He was especially critical of the 1848 French Constitution (which established the Second French Republic), condemning the document for setting up a directly elected president who had the right to pardon criminals, dismiss local and municipal councils, initiate foreign treaties, and, most damningly, appoint and fire ministers without consulting the National Assembly. Marx insisted that this produced a president with “all the attributes of royal power” and a legislature that “forfeit all real influence” over the state’s operations. The constitution, he charged, had merely replaced the “hereditary monarchy” with an “elective monarchy.”

One reason Marx polemicized against powerful executives was that he was concerned they escaped popular control, oversight, and scrutiny. He was also wary of the personal nature of presidential power, with leaders portraying themselves as the “incarnation . . . of the national spirit,” “possesses a sort of divine right” bestowed on them “by the grace of the people.”

Reading these comments today, it is easy to think of President Donald Trump. And, indeed, there are some intriguing parallels between Trump and Louis Napoleon (the president who eventually overthrew the Second Republic). But the more structural problem is the United States’ imperial presidency, which is untethered from meaningful congressional oversight (and whose creation was actively abetted by the Democratic Party). Similar problems beset the British constitution and were exploited by Tony Blair during the Iraq War and Boris Johnson during the Brexit negotiations. France’s current constitution, adopted in 1958 under Charles de Gaulle, was specifically designed to concentrate power in the hands of the executive (a legacy enthusiastically embraced by President Emmanuel Macron).

Marx’s writings remind us not to confuse the critique of parliamentarianism (the idea that elected officials are the prime actors in reform projects) with a wholesale attack on legislatures. Existing parliaments undoubtedly leave much to be desired, and there are huge and long-standing organizational questions about the relationship between the wider socialist movement and socialist representation in parliament.

But the answer cannot be to rely on the power of the courts to defend and advance progressive goals or to place a socialist at the helm of an all-powerful executive — or, for that matter, to swear off seeking legislative representation entirely. The legislature is the most democratic of the three state branches — the US Federalist founders were keen to limit its powers for a reason — and democratic socialists should defend it from executive and judicial intrusion.

Transforming the Bureaucracy

Marx’s ideas on representation and the legislature would imply serious and far-reaching reforms to most modern representative governments. But it’s his views on bureaucracy that depart most radically from the political systems we are familiar with.

Marx sought a fundamental transformation of the state that would put ordinary workers at the heart of public administration. He proposed opening up the state’s bureaucracy to competitive elections and subjecting it to the same sanctioning power of recall that he advocated for representatives. In Marx’s eyes, this would turn the state from a separate, alien body that ruled over the people into one under its control. It would transform “the haughteous masters of the people into its always removable servants, a mock responsibility by a real responsibility, as they act continuously under public supervision.”

These comments were in line with Marx’s longstanding distrust — even loathing — of bureaucrats (ironic given the standard association of Marx with bureaucratic statism). He denounced them as a “trained caste,” an “army of state parasites,” a class of “richly paid sycophants and sinecurists.” And he maintained that “plain working men” were capable of carrying out the business of government more “modestly, conscientiously, and efficiently” than their supposed “natural superiors.”

Marx’s vision is undoubtedly appealing. Too often, ordinary people are subject to the whims of officious bureaucrats — forced to jump through endless hoops merely to secure the means of their existence. But in a modern, complex society, his vision would confront formidable hurdles, including insufficient technical expertise and corporate capture of inexperienced administrators. At the very least, it is hard to imagine a heavily democratized bureaucracy without an accompanying economic sphere that gave people drastically more time to take part in public administration (and where people wanted to assume such duties).

Marx’s writings don’t offer any real guidance about how his plan to democratize the bureaucracy could work. Insofar as he had a model in mind, it seemed to approximate ancient Athens, where citizens rotated between being ruler and ruled through the use of lotteries that selected administrative positions (a feature of Athenian democracy that was barely understood and largely forgotten when Marx was writing).

Notably, it is this element of ancient democracy that has recently re-emerged in democratic theory and practice as a potential way to address some of representative government’s failings. There is much discussion, for instance, of Citizen Assemblies — randomly selected groups of people that are tasked with deliberating and making recommendations on either specific policies or constitutional reforms. Citizen assemblies have been used to discuss constitutional amendments in Ireland and the design of electoral reform proposals in British Columbia and Ontario, Canada, and an ongoing campaign is pressing to include them in any future UK constitutional convention.

Additionally, US political theorist John McCormick has put forward an intriguing proposal for a modern form of the Roman plebeian tribune. The body would have fifty-one members, drawn by lot from the wider population (save for the wealthiest 10 percent), and could propose legislation, initiate referendums, and impeach public officials.

This kind of sortition might be one way to realize some of Marx’s hopes for a political system where citizens directly carried out government and public administration tasks.

Marx the Democrat

Marx always believed that representative government was an enormous advance over the absolutist regimes it replaced. But he also disputed its equation with “democracy.” He instead argued that the institutional changes outlined above would generate a political system with “really democratic institutions.”

According to Marx, these structures were vital to advancing socialism in the economic sphere — it was a serious error to think that socialists could simply take over existing state institutions and steer the ship toward socialism (an error Marx admitted having sometimes made himself). Socialists, he wrote, “cannot simply lay hold of the ready-made State machinery, and wield it for its own purposes.” If political power was to remain “in the hands of the People itself,” it was imperative for the people to “displac the State machinery, the governmental machinery of the ruling classes by a governmental machinery of their own.”

This remains one of Marx’s most important political and constitutional insights: radical economic transformation must go hand in hand with radical political transformation. Disregarding the latter undermines the former.

At a time when socialism is resurgent but fragile, Marx’s views on popular democracy deserve closer attention. How we choose to realize his insights is up to us.

Bruno Leipold teaches political theory at the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Jacobin is a leading voice of the American left, offering socialist perspectives on politics, economics, and culture. Subscribe.

Spread the word