When she was in third grade, in the mid-’80s, Robin Rue Simmons took the bus to a playdate at the home of a friend she’d never visited before. The trip was a quick one. At eight square miles, Evanston wasn’t tiny, but it was far from sprawling. As she crossed the North Shore Channel and headed up McCormick Boulevard, then west along Central Street, she noticed a change. People on the sidewalks were white, not black. There were shops and grocery stores. As the bus neared her friend’s street, she saw neatly trimmed lawns, with poplars and elms shading wide, clean streets. Unlike in her neighborhood, the 5th Ward, with its aluminum-sided two- and three-flats separated by narrow alleys, the lots here were spacious. The façades were limestone and brick, with bright white trim and Spanish tile roofs. Manicured hedges guarded many of the homes, most of which had their own driveways, some of them laid in elegant herringbone patterns. By the time she’d arrived at her friend’s house, she felt as if she had entered a foreign land.

It’s not that the neighborhood struck her as better than her own, just different. She loved the 5th Ward. It was comfortable, happy, familiar. Rue Simmons was black, her family was black, her schoolmates and teachers were black. After school, she made crafts at a black-run family center. In her neighborhood, as the saying went, you couldn’t sneeze without someone offering a handkerchief. People looked out for each other. Rue Simmons felt safe and cared for in the 5th Ward, and certainly not poor.

And yet, once she’d followed the curved walkway to her friend’s front door, been led inside by a housekeeper, and gazed at the high ceilings and gleaming surfaces, the contrasts were harder to reconcile. In her neighborhood, three generations often shared the same two-flat, children sleeping in bunk beds. At her friend’s home, each kid had a bedroom, and there were still rooms left over for guests. Her friend’s mother served snacks, something Rue Simmons knew a visitor to her own home would likely not be treated to, not out of a lack of hospitality, but because both her parents worked full time.

The day was fun — her friend’s family was gracious and kind — but she went home feeling not jealous, really, but unsettled. Why were all the houses in her neighborhood so small and cramped, and why did only black people live in them? That feeling stuck with her for a long time after that, through high school and college and the early years of her professional life. It gnawed at her. It was still there on the day in 2017 when, at the age of 41, she was sworn in as the alderman of the same ward where she had grown up and was now raising a family of her own, alongside neighbors who were still mostly black.

And the realization dawned: She might be able to do something about that unsettled feeling, tap into it and use it to make something happen. Maybe something big.

Alderman Robin Rue Simmons, pictured on the block she grew up on in Evanston’s 5th Ward, says her own struggles to buy a home there were a big motivation in her push for reparations. PHOTO: JEFF MARINI

In late November of last year, Rue Simmons and her eight fellow aldermen filed into the Evanston City Council chamber and took their seats on the dais that spans the front of the room. On the wall behind them hung the city seal: a lighthouse set against Lake Michigan with the year of Evanston’s incorporation, 1863.

Most council meetings unfold unremarkably, devoted to the minutiae of local governance: committee reports, utility updates, new business, old business. The agenda on this day, however, focused on a single item brought to the table by Rue Simmons after months of negotiation and years of groundwork. The item before the council: 126-R-19, “A Resolution Establishing a City of Evanston Funding Source Devoted to Local Reparations.” Section 2 of the two-page document laid out the measure’s central provision plainly: “The Chief Financial Officer is hereby authorized to divert all adult use cannabis funds received by the Illinois Department of Revenue for sales of adult use cannabis to a separate fund in a City account for local reparations.” The initial investment was set at $10 million, its specific uses left unstated beyond a reference to “housing assistance and relief initiatives for African American residents in Evanston” and “various Economic Development programs and opportunities for African American residents and entrepreneurs in Evanston.” Anyone who wanted to could contribute to the fund.

The measure passed 8 to 1. And with that, this college town of 74,000 became the first municipality in America to commit public dollars — in this case, tax revenue from the soon-to-be-legalized sale of recreational cannabis — to reparations for its black citizens. In doing so, Evanston’s leaders accomplished something that a generation of civil rights activists hadn’t managed to elevate beyond a legislative pipe dream. Consider John Conyers: The U.S. representative from Michigan, who died in October, tried in vain for 30 years to introduce a bill in Congress merely seeking the establishment of a commission to study the issue. Indeed, the very word “reparations” — generally understood to mean compensating black people for the wrongs of slavery and its aftermath — is enough to prompt harsh rebuttals from the political right and misgivings even from some on the left.

In a 2016 interview with the author Ta-Nehisi Coates, whose widely read article “The Case for Reparations” had appeared in the Atlantic two years earlier, no less than Barack Obama said, “It is easy to make that theoretical argument. But as a practical matter, it is hard to think of any society in human history in which a majority population has said that as a consequence of historic wrongs, we are now going to take a big chunk of the nation’s resources over a long period of time to make that right.” A Gallup Poll in 2019 found that 67 percent of Americans opposed the idea (though 73 percent of black Americans were in favor).

Eighteen years ago, another Evanston alderman, Lionel Jean-Baptiste, had gotten as far as introducing a resolution acknowledging the need for reparations, but lacking a funding provision, it wound up being little more than a well-intentioned pronouncement that soon faded from public consciousness. Now, suddenly, Rue Simmons was being contacted by officials and activists from near and far seeking her blueprint: an alderman in Waukegan; a councilman in Akron, Ohio; the president of the National Black Caucus of Local Elected Officials; the director of the Race, Equity, and Leadership initiative at the National League of Cities.

Rue Simmons also received her share of nasty emails after the measure passed (“Blacks need to own up to their own failures,” “No more handouts,” “Ghetto lotto at its finest”). And reader comments published by local news outlets decried a perceived lack of transparency (one called the public vetting process “under the radar,” saying the community meetings held before the vote weren’t adequately publicized) and echoed common reverse-racism arguments against reparations (“Is the City of Evanston really going to use the color of someone’s skin to determine whether they get taxpayer dollars to buy their house?” asked a commenter at the online newspaper Evanston Now).

As for the lone “no” vote among the nine City Council members, three of whom are black, it came from white alderman Thomas Suffredin, who couched his opposition in strictly fiscal terms. “In a town full of financial needs and obligations,” he wrote in a newsletter to the residents of his ward, “I believe it is bad policy to dedicate tax revenue from a particular source, in unknown annual amounts, to a purpose that has yet to be determined.” But the major political backlash and even the lawsuits that Rue Simmons and her colleagues had been bracing for have yet to materialize.

This is not to suggest that the road ahead is free of obstacles — thorny issues about how the funds will be disbursed and to whom remain mostly unaddressed — but those uncertainties have hardly diminished what has been widely considered a monumental achievement. How did Evanston succeed where so many others had failed? Certainly, nimble political maneuvering played a part, but so did a canny effort to get people to rethink what reparations mean. In the eyes of Rue Simmons and her allies, the injustices that Resolution 126-R-19 seeks to address are more than just centuries-old “historical wrongs” described in school textbooks. They are a living legacy of institutional discrimination in Evanston whose repercussions are still being felt.

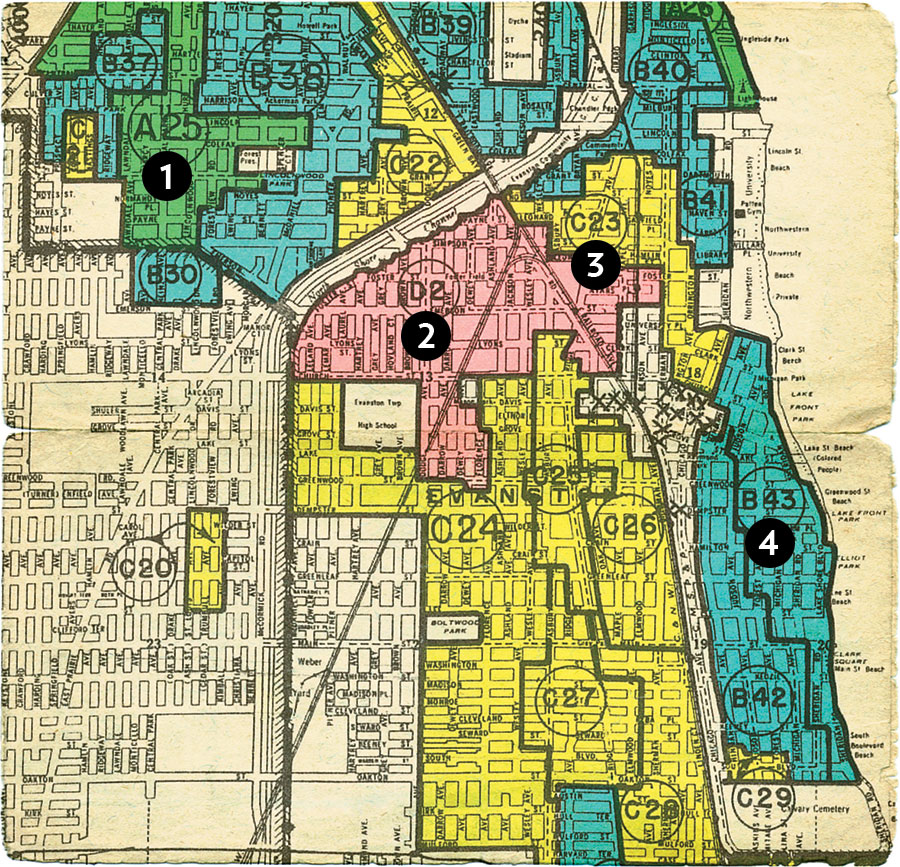

Decades-Old Discrimination, Mapped

This map of Evanston issued by the federal government’s Home Owners’ Loan Corporation in 1940 served as a de facto redlining guide for real estate agents. It divided the city into color-coded zones, each assigned a “security grade” from A to D, and used racist language in describing the neighborhoods. Sector D2 (labeled with a 2) corresponds to the mostly black 5th Ward.

MAP: MAPPING INEQUALITY/ROBERT K. NELSON/UNIVERSITY OF RICHMOND DIGITAL SCHOLARSHIP LAB/NATIONAL ARCHIVES (HOLC)

1. “It has practically all the characteristics of a first class neighborhood and few disadvantages. Its future seems well assured because of its uniformity and class of occupant.”

2. “There is not a vacant house in the territory, and occupancy, moreover, is about 150 percent. … This concentration of negroes in Evanston is quite a serious problem for the town as they seem to be growing steadily and encroaching into adjoining neighborhoods.”

3. “This is a convenient location sandwiched between two desirable areas and a concentration of negroes on the southwest.”

4. “Each year a separate bathing beach is designated for the large colored population living in Evanston, the thought being a constant shifting of this location would minimize the adverse effect of negro bathing facilities.”

The clustering of much of Evanston’s black population into a single small neighborhood hard against the North Shore Channel is no accident. By the end of the 19th century, there were scarcely more than 100 black residents in what was then a town of 20,000 people, says Dino Robinson Jr., founder of the Shorefront Legacy Center, an archive of local black history. In the early 1900s, when the black population topped 1,000, the city’s white real estate brokers funneled any prospective black homebuyers into the area “bounded by Orrington Avenue on the east, Simpson Street on the north, Dodge Avenue on the west and Greenwood on the south,” Robinson writes in his book A Place We Can Call Our Home. An ordinance passed by the City Council in 1919 zoned the blocks surrounding the black enclave — by then a triangle bounded on the west by the North Shore Channel (completed in 1910), on the south by Church Street, and on the east by commuter train tracks, borders that correspond closely to those of the 5th Ward — for commercial use only, effectively creating a ghetto by eliminating the possibility of residential expansion.

From those earliest days, the mere presence of black people in Evanston caused white residents anxiety, which was frequently stoked by the local press. A 1904 article in the Chicago Daily Tribune bore the headline “Influx of Negroes Alarms the Residents of Evanston, Wilmette, Winnetka, and Glencoe.” A year earlier in the same paper, an article titled “A Rope Might Do” called on black residents of Evanston to put a stop to a “colored man” the paper said was frightening women.

By the end of the 1930s, Evanston’s African American population had surpassed 6,000, out of a total of 65,000 residents, and the 5th Ward was 95 percent black. The city was kept strictly segregated by an informal system in which real estate agents refused to sell to blacks outside the 5th Ward and many white homeowners added covenants to their deeds stipulating that the properties not be sold to blacks. Likewise, Robinson says, banks generally would not approve home loans to blacks buying outside the triangle, nor would they loan to the few who wanted to build on lots they’d managed to purchase near the lake years earlier.

Some black buyers bypassed the banks and bought directly from white property owners, who locked them into usurious private contracts, selling $12,000 houses for $22,000, says real estate analyst Mark Alston, whom Rue Simmons tapped for historical context as she built her argument for reparations.

At the outset of World War II, the federal government’s Home Owners’ Loan Corporation issued a map for real estate agents that assigned grades to Evanston’s various neighborhoods: “A” areas contained the “highest class of occupant”; “B” areas were less coveted but “still desirable”; “C” areas were considered vulnerable to “infiltration of a lower grade of population”; and “D” areas were deemed home to an “undesirable population or an infiltration of it.” Deepening divisions further was the government’s practice of redlining, so named for the red lines drawn on maps around areas considered too risky for federal mortgage insurance.

By 1960, Evanston remained highly segregated, scoring 87 out of 100 on a segregation index created by researchers Karl and Alma Taeuber. A number of visits to the suburb by Martin Luther King Jr. in the early 1960s and protests by the black community pushed the City Council to pass an open-housing ordinance in June 1966, but the measure was vetoed by the mayor. It wasn’t until the passage of the federal Fair Housing Act in 1968 that legal discrimination formally ended, though unofficial discrimination persisted. As did segregation. Even today, the census tract encompassing most of the 5th Ward is 54 percent black. The tracts just to its west, north, and east range from 3 to 7 percent black. The tract encompassing the city’s northwest corner is less than 1 percent black.

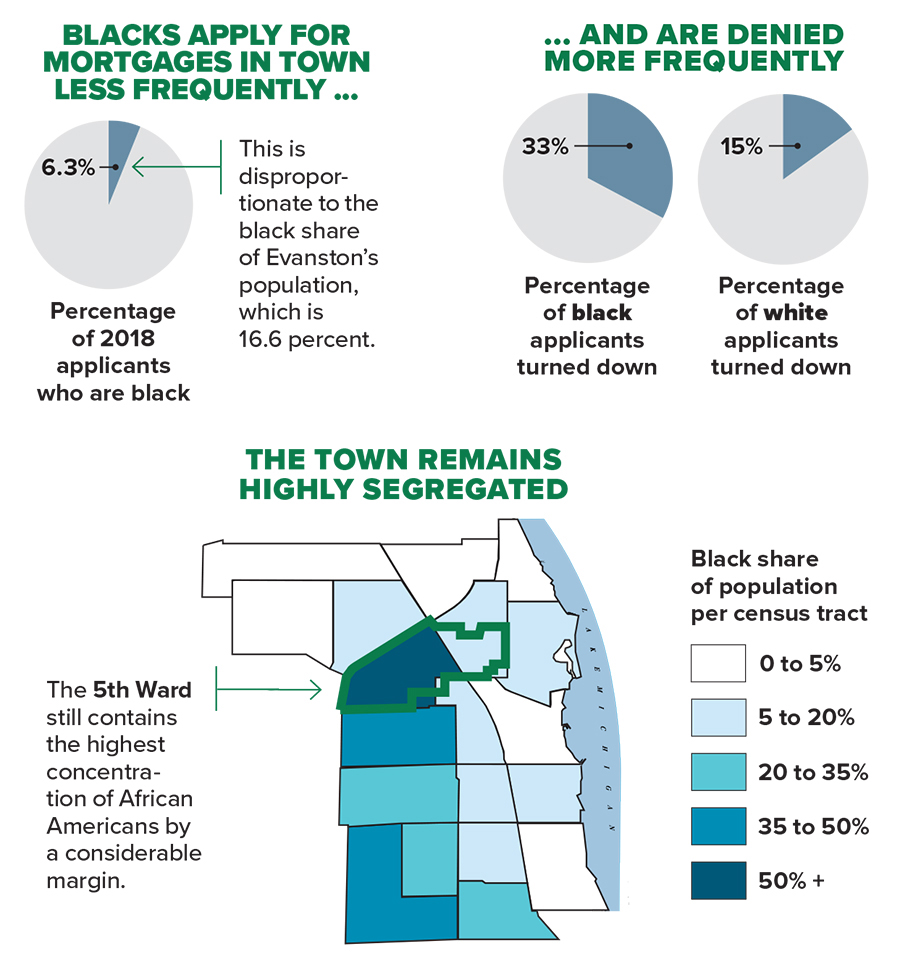

In a presentation to a local chapter of the National Association of Real Estate Brokers ahead of the November reparations vote, Alston noted that across Chicago, the home ownership gap — 39 percent for blacks versus 74 percent for whites — is higher than when the Fair Housing Act was passed. Alston also pointed out that in Evanston specifically, many more whites are approved for mortgages than blacks. Of the 218 mortgages in Evanston issued by JPMorgan Chase in 2018, 150 went to whites and 17 to blacks.

“It isn’t because blacks aren’t trying hard enough or don’t want to own a house,” Alston told the trade association. Rather, blacks — who make, on average, 60 cents for every dollar earned by whites nationwide and were disproportionately affected by predatory lending practices during the Great Recession — have had a much harder time building generational wealth.

Alston argued that reparations funds specifically earmarked to help black people buy and keep their homes would allow them to increase their wealth, which could then be passed down to the next generation, breaking the cycle of disparity. To opponents of reparations who contend that the playing field has leveled, Alston offered an analogy: “If I give you a big enough head start, I can’t catch you.”

SOURCES: Home Mortgage Disclosure Act and U.S. Census Bureau data for 2018

Toward the end of March, I pulled up in front of the tree-shaded split-level where Rue Simmons and her family have lived for the past 10 years. The alderman, who works as a small-business consultant and entrepreneur in addition to her municipal job, had suggested we take a social-distancing-compliant drive around the 5th Ward and nearby neighborhoods. She climbed into her car and, for the next hour or so, led me on a tour while we talked by cellphone.

“When it comes down to someone coming up with an actual plan, it’s like, ‘Oh, slow up a minute. Oh, you want money? My tax money?’ ”

“As you can see, the property standards and density are completely different when you cross over to the east side of the ward,” she said. We’d been driving along Dodge Avenue — blocks of tightly spaced two-flats and small three-bedroom houses with postage-stamp yards — and had turned onto Emerson Street before crossing Sherman Avenue, and now we were seeing generously spaced Victorians and Dutch Colonials spooling by.

Entering downtown Evanston, we passed a Whole Foods, a Cupitol coffee shop, and the Evanston Athletic Club. We continued along more streets lined with boutiques and restaurants, then swung north and west, back into the heart of the 5th Ward. Almost immediately the stores and businesses thinned out, then all but disappeared. Rue Simmons pointed out a convenience store at Emerson Street and Dewey Avenue and said it was the only food shop in the neighborhood. Kids in the ward had to be bused to the nearest schools. A visit to a library or a hospital also required a trip outside the ward. Despite the enduring lack of resources, she said, “there are still many, many black families that have lived here for four generations.”

As we turned onto Wesley Avenue, I noticed handsome newer homes with landscaped yards. “These are nice,” I said offhandedly.

“They are,” Rue Simmons agreed. Then she explained that this stretch of Wesley, on the ward’s eastern border, had attracted developers who quietly bought up houses and either demolished or gut-renovated them. Given that the average income for black families in Evanston is $44,000 — as opposed to $90,000 for whites — most ward residents “wouldn’t even be able to afford the taxes on these properties,” she said. “Don’t get me wrong, community development is welcome here. As you can see, some of the homes in the ward have deteriorated. But we need responsible development that has to include the needs of the community.”

Later, Rue Simmons told me that when she sought to buy her own home in the 5th Ward a decade ago, she “saw all the barriers” to living in Evanston: the difficulty of finding a home that fit both her budget and her family; the taxes on what she describes as overassessed properties, especially in the 5th Ward; the struggle to come up with a down payment. All of those concerns were front of mind when she decided to make a bid for the aldermanic seat being vacated by Delores Holmes in 2017.

Within a year of winning that election, Rue Simmons began to talk in earnest with her colleagues in city government about ways to give material help to Evanston’s black residents. For the most part, she found sympathetic ears. Achieving racial equity had long been a City Council goal — going back to the resolution introduced by Jean-Baptiste 18 years ago — and in 2018 the suburb formed its own Equity and Empowerment Commission, with a stated mission to “identify and eradicate inequities in City services, programs, human resource practices, and decision-making processes.” But real progress had been elusive. “We’re dedicated to diversity,” Rue Simmons says, “but when it comes down to someone coming up with an actual plan, it’s like, ‘Oh, slow up a minute. Oh, you want money? My tax money?’ ”

In the spring of 2019, the alderman sent an email asking the commission to take up the issue of funding reparations. “What we’re doing is not enough,” the message read. “We need to do something radically different.” She described the email as a “discussion starter” but not much more than that. “It was received and acknowledged, but there wasn’t any action.” So Rue Simmons sent more emails and finally succeeded in initiating formal deliberations. In late summer, she filed an official request for the commission to put the idea of money for reparations on the agenda.

As part of her persuasion campaign, she arranged a series of public meetings. Given the divisiveness that the idea of reparations has engendered in national politics, she steeled herself for shouting matches and acrimony. Instead, a diverse group of residents showed up, including some who had lived through the redlining and Jim Crow policies of the postwar years. People shared stories of discrimination and their struggles to get by. Rue Simmons says that not a single attendee voiced opposition to the reparations measure. If a substantial number of Evanstonians were against the idea, none of them turned out in person to protest it.

Still, there was the vexing question of funding the effort. Rue Simmons initially proposed a graduated real estate transfer tax on the sale of properties valued at more than $1 million. She also considered an amusement tax for public events. But new taxes are a political third rail, and the ideas met with skepticism even from allies.

In the end, it wasn’t Rue Simmons who came up with the idea of diverting cannabis revenue. It was Ann Rainey, a white alderman representing the 8th Ward, which extends along Evanston’s southern boundary. At first, Rue Simmons was hesitant, wary of the optics of using proceeds from the sale of a drug that had landed a disproportionate number of black people in jail. “As soon as it was on the table,” she says, “I requested that the staff give me a report on our marijuana arrests.” The numbers were shocking. African Americans, who make up 16 percent of Evanston’s population, accounted for more than 70 percent of arrests.

On the other hand, there was a certain moral logic to redirecting cannabis funds into the very community that had been hit hardest by unequal enforcement and prosecution. What’s more, it would avoid introducing a brand-new tax or hiking existing ones — technically, taxpayers wouldn’t feel it.

A crucial piece of groundwork was laid in June, when the council adopted a resolution affirming the city’s commitment to end structural racism and achieve racial equity. “In order for the City of Evanston to fully embrace the change necessary to move our community forward,” it read in part, “it is necessary to recognize, and acknowledge its own history of discrimination and racial injustice. … The City of Evanston government recognizes that, like most, if not all, communities in the United States, the community and the government allowed and perpetuated racial disparity through the use of many regulatory and policy oriented tools.” With the passage of a resolution establishing the moral and political foundation for reparations, Rue Simmons’s measure passed overwhelmingly five months later.

A December town hall meeting to discuss the new ordinance included testimonials from actor Danny Glover and former alderman Lionel Jean-Baptiste (pictured with wife Lenore), who’d first proposed a reparations resolution 18 years ago. PHOTOS: KEVIN TANAKA/PIONEER PRESS

Less than two weeks after the historic vote, an overflow crowd of 600 people turned out for a town hall meeting at the First Church of God on Simpson Street. The meeting’s purpose was to solicit ideas on how the reparations money should be spent — the resolution was short on details, with specifics to be decided under the guidance of a newly formed subcommittee — but the gathering soon turned festive.

“This is an extraordinary moment for us to celebrate,” actor and activist Danny Glover, the keynote speaker, told the group. Glover, along with Ta-Nehisi Coates and other proponents, had testified before Congress months earlier on the need for reparations; as in years past, little beyond platitudes and promises had come out of those hearings. This day, Glover was exultant, praising Rue Simmons and others “who have stood up and put their foot in the fire.”

Some speakers shared personal experiences, including Lionel Jean-Baptiste, now a Cook County Circuit Court judge. The former alderman wept as he recounted his ancestors’ experience with slavery in Haiti, describing “the rape and dismemberment, the whips and lashes.” Other speakers, moved by his words, leaned in to comfort him. Rue Simmons spoke too, vowing to meet with “stakeholders and community members to weigh in on what we need to do to get this right.”

The fervor has died down, leaving behind the daunting task of implementation. How much revenue will cannabis sales generate? (The town, which under state law can start collecting cannabis taxes on July 1, expected up to $750,00 per year.) How will those funds be distributed? To whom exactly? Starting when? Some have suggested a sort of grant program allowing black residents to apply for housing assistance, or for help starting a business, but nothing definitive has been decided. “Just the notion of it is tough because this is the first municipality that said, ‘OK, let’s do this,’ ” says Rue Simmons. Whatever form the initiative takes, success must be defined by measurable outcomes, she says. “I’m asking for the highest-impact policy. I don’t want to disburse this, and then, two years later, there is no impact. That’s not a success.”

Much of the subcommittee’s work has ground to a halt because of the coronavirus pandemic, but its members had originally been hopeful that the first money could be distributed as early as the beginning of next year. For now, like most of us, Rue Simmons is revising her timeline and expectations in the face of changed circumstances.

She has also, like most of us, been moved to reconnect with old friends. In April, she decided to call the schoolmate whose house she’d first visited in third grade. They’d been in touch sporadically over the years, but Rue Simmons had never told the friend how unsettling that first playdate was for her. “I wanted you to know that I loved your family and it was wonderful,” she told her friend over the phone, “but that it was also difficult.” To Rue Simmons’s surprise, the friend confessed that she’d been uneasy too when she visited her in the 5th Ward.

As they wrapped up the call, the friend congratulated the alderman on her reparations victory.

“We still have a ways to go,” Rue Simmons said.

“I know,” replied the friend. “Let me know how I can help.”

Bryan Smith is an award winning staff feature writer with Chicago magazine and author of The Breakaway: The Inside Story of the Wirtz Family Business and the Chicago Blackhawks. Here you'll find links to my greatest hits and the occasional musing about writing.

This article appears in the June-July 2020 issue of Chicago magazine. Subscribe to Chicago magazine.

Spread the word