As part of a network of Black pastors, the Rev. Floyd James is working with Rush University Medical Center to establish more coronavirus testing on the West Side.

James, the pastor of Greater Rock Missionary Baptist Church in North Lawndale, also has been trying to put doctors in touch with community members to help answer questions about COVID-19, which has spread aggressively in Black communities on the West Side and South Side.

Hospitals like Rush, one of Chicago’s biggest, have been trying desperately to recruit people of color for vaccine research to help ensure the therapies are safe and effective in the most vulnerable populations.

But that’s a tough sell, according to James, who — along with two dozen family members — came down with the virus earlier this year and says it left him feeling “like Mike Tyson’s punching bag.”

He’s uncertain about whether many West Side residents will get a shot once the vaccines are available, let alone take part in the studies making sure they work.

The Rev. Floyd James at Greater Rock Missionary Baptist Church in May holding a touchless thermometer the church has used to check parishioners coming to church. Tyler LaRiviere / Sun-Times

“We’ve been hoodwinked so many times with vaccines,” James says, repeating a sentiment often heard in Black communities. “We’ve been experimented on by the government, by the scientific community and the hospitals.”

There is a deep distrust among many Blacks regarding medical studies. The U.S. government’s Tuskegee syphilis research — which withheld treatment of poor Black men over a 40-year period — often comes up. That wariness has been reflected in low participation by Blacks in medical studies in Chicago and nationally.

“The mistrust built up over years is well-founded,” says Dr. Monica Peek, an associate professor of medicine and health disparities researcher at the University of Chicago. “There have been repeated experiences that degrade the value of black lives — not only in health care.”

“African Americans are disproportionately burdened by this pandemic,” Peek says. “It will be a double tragedy if African Americans refuse to take the vaccine.”

Dr. Monica Peek: “It will be a double tragedy if African Americans refuse to take the vaccine.” University of Chicago

That’s a problem hospitals have to address, Peek says, because Black and Latino Chicagoans are being infected with COVID-19 and dying from the virus disproportionately compared with whites. Blacks account for more than twice the number of coronavirus deaths as whites, and Latinos account for the highest number of cases, more than double that of whites, city data show.

It’s a tough challenge for Chicago’s large academic hospitals, which are still trying to recruit hundreds of volunteers to test the safety and effectiveness of the vaccines but struggling to recruit enough Black and Brown participants. African Americans have been particularly hard to enlist.

When the University of Illinois Hospital at Chicago put out a call for vaccine study volunteers over the summer, it aimed to get at least 1,000 — a majority of them Black and Latino. More than 8,000 people volunteered for the trial of the vaccine made by biotech company Moderna. But most of them were white. UIC and the University of Chicago, its research partner, eventually recruited a majority of minority participants. But the overall number of people in the trial ended up less than 500.

Dr. Richard Novak hopes to get 1,500 volunteers for a new UIC COVID-19 trial, testing Johnson & Johnson’s COVID vaccine. Joshua Clark

Nationally, Moderna asked researchers to go back and recruit more minorities because of low participation. UIC’s early results were submitted to Moderna, which recently announced its vaccine was almost 95% effective.

The Moderna study was one of a number of government-funded trials for which federal health officials said minority participation would be vital, says Dr. Richard Novak, the lead UIC investigator.

Novak has reached out to community groups, pastors and Latin American consulates in his efforts to recruit more minorities for studies. UIC plans to enroll soon in another vaccine trial, this one testing Johnson & Johnson’s COVID vaccine. Initially, researchers hoped to attract 1,500 patients, but Novak says that goal might not be reached. He wants to recruit a large number of Black and Latino volunteers.

The University of Chicago and Northwestern University also plan to conduct studies of the J&J vaccine and say they are working hard to get minority volunteers.

Blacks make up 13% of the U.S. population but account for more than 20% of the deaths from COVID-19 and only 3% of those enrolled in vaccine trials, according to an article in the New England Journal of Medicine last month.

Bonnie Blue, getting blood drawn by nurse Corey Ringhisen, was one of the first to sign up for a COVID-19 vaccine clinical at the University of Illinois at Chicago. She volunteered, despite her family urging her not to, because “this is something that’s bigger than me.” Joshua Clark / University of Illinois at Chicago

Bonnie Blue’s family urged her not to take part in a COVID-19 vaccine study at UIC. It’s too dangerous, she was told, echoing what she’s heard much of her life: Black people have been treated like guinea pigs in medical experimentation.

“There is an issue of trust — a big, very valid issue of distrust,” says Blue, 68, who decided to join the study. “I see why my family was upset. But this is something that’s bigger than me.”

Blue hopes that distrust will fade in time. But she doesn’t blame anyone for their fears.

“I would never shame somebody or push someone to do what I did,” she says. “We do need more people of color and people who are older to take part in these trials. But I also know some family members say, ‘No way — don’t do it.’ ”

Before agreeing to participate, Blue met with Novak and asked him a number of questions, like: Will she know if she gets the vaccine or a placebo? She won’t until more study data are revealed at a later date.

After peppering the doctor with questions, she asked, “If I was your mother sitting here, what questions would you tell her to ask?”

Novak laughed and told her, “I think you pretty much got it all,” Blue says.

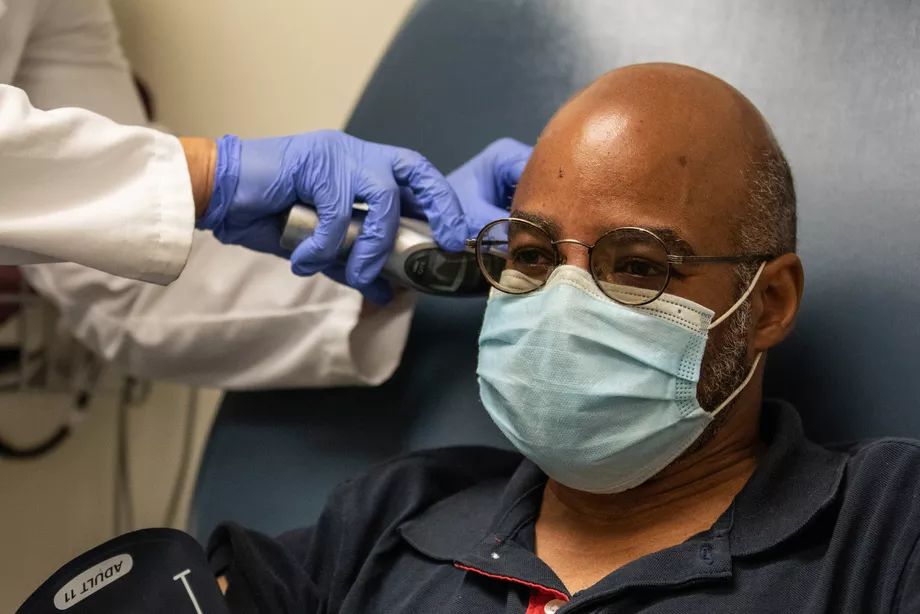

Eduardo Rollox, having his temperature taken, was among the volunteers for in the Moderna coronavirus vaccine trial at the University of Illinois Hospital at Chicago. Joshua Clark / University of Illinois at Chicago

Eduardo Rollox, 55, of Evanston, also had friends and family tell him he was crazy to consider enrolling in a vaccine study. But, after consulting with his doctor, he was one of the first volunteers for the UIC study.

Rollox says he has an underlying health condition that would put his life at risk if he is infected with COVID. Born in Panama, Rollox moved to the United States at 7. He has faith in science but understands the anxieties.

“It’s going to take a long time for the distrust to go away,” Rollox says.

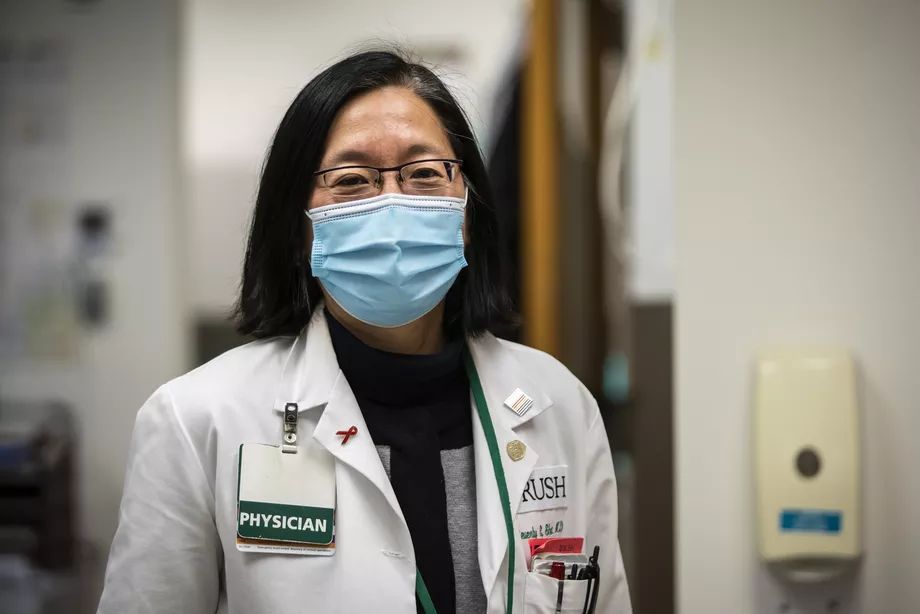

Dr. Beverly Sha, an infectious disease expert at Rush University Medical Center, is conducting a clinical trial for a COVID-19 vaccine developed by AstraZeneca. Ashlee Rezin Garcia / Sun-Times

Like a lot of infectious disease experts, Dr. Beverly Sha spent years studying HIV. Treating people with AIDS gave her the chance to forge relationships — bonds that often helped recruit participants for studies of various medicines. COVID doesn’t afford that opportunity, she says.

“What I’ve come to realize: One huge thing I don’t have is a relationship with the patient,” Sha says.

Emilio Cici, 42, of Burr Ridge, gets a shot Thursday at Rush University Medical Center as part of a clinical trial for a COVID-19 vaccine developed by drugmaker AstraZeneca. Ashlee Rezin Garcia / Sun-Times

This COVID-19 vaccine developed by AstraZeneca is being tested at Rush University Medical Center Ashlee Rezin Garcia / Sun-Times

Without such bonds, hospitals have to cast a wide net to find Black and Latino volunteers, she says. She likens the task to randomly stopping people on the street to recruit them.

“I could stop 100 white people, and maybe 50 say, ‘Tell me more,’ ” Sha says. “But I stop a hundred Black or Latinx, and maybe only 10 show an interest. Not zero. So, in order to recruit enough, we have to extend the net that much wider.”

Rush is one of two sites, along with Cook County Health, recruiting for a study of another vaccine developed by the British drugmaker AstraZeneca. For Rush’s AstraZeneca vaccine trial, Sha hopes to recruit 500 volunteers, at least a quarter of them minorities, with 10% Black participation.

Sha knows how hard that will be. She says a government registry available to researchers showed that, of more than 10,000 people in the Chicago area who signed up to volunteer for COVID-19 studies, only 4% were Black, and 9% were Latino.

Dr. Temitope Oyedele, principal site investigator of the Cook County Health vaccine trial: “We definitely want to recruit people in our health system, people of color.” Cook County Health

Dr. Temitope Oyedele, an infectious disease expert and principal site investigator of the Cook County Health vaccine trial, hopes to sign up at least 250 participants. And he’s confident a large portion will be minority, reflective of the patient population of John H. Stroger Jr. Hospital and the rest of the county health system.

“We’ve built a lot of relationships,” Oyedele says. “We definitely want to recruit people in our health system, people of color.”

Cook County already has tested other COVID therapies, including two experimental antibodies treatments, that attracted high minority participation, Oyedele says.

Dr. Ephriam Grimes, associate medical director of Advocate Trinity Hospital’s emergency department: “I know the distrust and sentiment is still there.” Advocate Trinity Hospital

A major question beyond the studies, is whether Blacks and other minority groups will trust a new vaccine, as one or more are expected to become available over the coming months.

Not right away, says Dr. Ephriam Grimes, associate medical director of Advocate Trinity Hospital’s emergency department.

“For my generation, we all had parents and grandparents very familiar with Tuskegee,” Grimes says. “As for the younger generations, I don’t know if those stories are passed down, but I know the distrust and sentiment is still there.”

Distrust of government, the history of Tuskegee and other experiments and racial disparity in the health system all play a part in the skepticism about the vaccines now being seen, Grimes says.

“Working on those disparities, improving health outcomes for minorities, you might get a little more trust down the road,” he says.

TO ENROLL IN COVID-19 VACCINE TRIALS

These COVID-19 vaccine trials are seeking volunteers or soon will be:

Cook County Health

Call (312) 869-4289 or go online to https://forms.office.com/Pages/ResponsePage.aspx?id=lSKSO4bof0GqqE5MTwadgqrQQI0zsUJNlG7fKZtU1xZUMVA1MkZGVlhKTU5KV0ZWTlBVOVFNV1JJNCQlQCN0PWcu Northwestern

Northwestern University

Go online to https://redcap.nubic.northwestern.edu/redcap/surveys/?s=HEMWD7PE33

Rush University Medical Center

Call (312) 563-1345 or email ID_Research_COVID19Vaccine@Rush.edu.

University of Chicago

Go online https://covidvaccinestudies.uchicago.edu/ or call (773) 834-3313

University of Illinois at Chicago

Call (312) 355-0656 or go online to coronaviruspreventionnetwork.org.

Brett Chase reports on environmental protection, pollution and public health under a grant from The Chicago Community Trust. He is a former investigative reporter for the Better Government Association , and, before that, worked at Bloomberg News, the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel and Crain's Chicago Business. He has a journalism degree from Drake University in Des Moines, Iowa, and has taught journalism at Loyola University in Chicago.

Spread the word