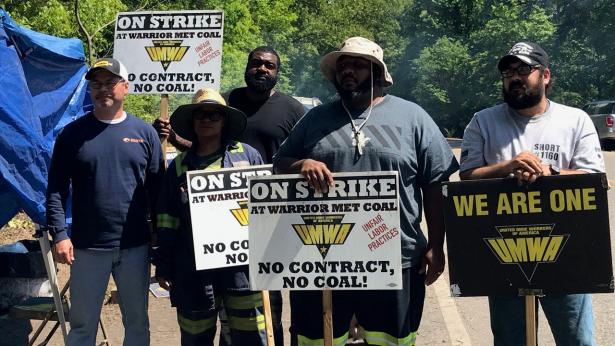

bout 1,100 coalminers in Alabama have entered 2022 still on strike, more than 10 months since they walked out back in April last year, making it the longest strike in the US since the Covid-19 pandemic began and the longest in Alabama’s history.

Workers started the unfair labor practice strike over claims of bad faith bargaining by Warrior Met Coal over a new union contract. In the previous contract settled in 2016, miners accepted several concessions, including a $6-an-hour pay cut and reductions in health insurance and other benefits as the mines switched employers in the wake of a bankruptcy.

The miners on strike have received support from US politicians such as Senators Bernie Sanders, Elizabeth Warren, Tammy Baldwin and Sherrod Brown, and received donations to their strike fund from dozens of labor unions across the US.

Over the past 10 months they have held rallies and extended protests to the Alabama state capitol to criticize the use of public resources for state troopers escorting strikebreaking replacement workers to the mines throughout the strike. Miners have also held rallies in New York City outside the offices of BlackRock Investment Group, the largest shareholder of Warrior Met Coal. As of 2 November, the strike has cost the company $6.9m.

“Most of us are working other jobs and receiving strike pay but some have crossed the line,” said Rily Hughlett, a miner at Warrior Met Coal, who has worked as a roof bolter in the mines for 13 years and believes that workers will win the strike. “We’re not going anywhere. The scabs and the bosses are all humored but he who laughs last laughs loudest.”

Since Warrior Met Coal took over the mines, the company has reported billions of dollars in revenue. A tentative agreement was reached in the first week of the strike, but overwhelmingly rejected by workers, and a new agreement has yet to be reached.

“What they’ve said openly in negotiations is that they’re just going to starve us out. They’ve said … and this on record, that ‘we have the money to pay what you’re asking, we do not have the desire to.’ That’s the kind of company these guys have been working for,” said Haeden Wright, president of the United Mine Workers of America auxiliary for two of the striking locals and the wife of a striking miner. “Through the journey, most of us are still holding out and trying to hold on, but it is hard.”

The unions’ auxiliary has focused on receiving and distributing weekly groceries to miners and their families throughout the strike and assisting families with needs such as bills. It recently organized a Christmas gift drive for miners’ families to ensure their children were taken care of over the holidays.

“For it to last this long and to have state troopers and to watch your tax dollars escort scabs into your job, that’s a hard pill to swallow,” added Wright. “That’s hard to watch and not be able to do anything about.”

Wright says that the strike has been hard but it has forced union members to strengthen their support systems with one another, and they have been able to spend a lot more time with their children and families after working 12-hour days, six or seven days a week in the mines.

Those long and demanding work schedules are one point of contention for workers in a new union contract. Wright’s husband, Braxton, has taken a temporary job during the strike at Amazon in Bessemer, Alabama, where he has become involved in supporting the unionization efforts at the warehouse. A new union election ordered by the National Labor Relations Board is scheduled to begin next month.

Warrior Met Coal has filed several court injunctions throughout the strike to severely limit or prevent striking miners from picketing outside the mines. Several union members and supporters have reported incidents where vehicles have hit or nearly missed individuals on the picket lines. The injunctions have been characterized as a rare move, an attempt by Warrior Met Coal to circumventthe NLRB and instead seek rulings from favorable local courts.

“We’re still negotiating with them. We still have not reached an agreement but we’re hopeful that we can get something pretty soon here,” said Larry Spencer, the District 20 field representative for the UMWA in Alabama.

He said the surge in Omicron cases during the pandemic and the holidays have made it more difficult to schedule negotiations on both sides, and the unions have paused picket lines temporarily to figure out how to comply with the court injunctions while ensuring members are kept safe.

“Workers have fought really hard to try to stay united and keep solidarity out there. We have a rally once a week and we’ve had a good showing of members and their families come out,” added Spencer. “The key is the membership. They are the ones pulling together and really fighting hard to make sure they get what they deserve through this company and get back to work as soon as possible.”

The US Department of Labor did not comment on whether its secretary, Marty Walsh, intended to intervene to assist in negotiations as he did with the 10-month-long nurses strike at St Vincent hospital in Worcester, Massachusetts, which ended with an agreement on 3 January.

A spokesperson for the labor department said: “Workers with unions have the power to advocate collectively for the working conditions they deserve, like fair wages and safety on the job. Workplaces are safer and more productive when workers have a seat at the table. We encourage businesses and unions to come together and work toward solutions in good faith.”

Warrior Met Coal has disputed claims that specific terms of previous contracts would be restored during the 2016 contract negotiations, and have rejected claims from workers and the union throughout the strike, but said it continued to negotiate in pursuit of a resolution.

Spread the word