The mother of four brought her children, ranging in age from grade school to high school, to the doctor’s office last summer for their annual checkup. When their pediatrician, Robert Froehlke, said that it was time for shots and several boosters and then mentioned the Covid vaccine, her reaction stunned him. “I’m not going to kill my children,” Froehlke recalls her saying, as she began to shake and weep. He ushered her out of the examination room, away from her children, and tried to calm her. “We’re just trying to help your kids be healthy,” he told her. But he didn’t press the issue; he sensed that she wasn’t persuadable at that moment. And he didn’t want to drive her away from his practice altogether. “That really shook me up,” he says.

In his 14 years of practicing medicine in Littleton, a Denver suburb, Froehlke had seen parents decline their children’s vaccines for the sake of a more “natural” lifestyle. He had also seen parents, worried about overstressing their children’s bodies, request that vaccinations be given on different schedules. But until the past nine months or so, he had rarely seen parents with already vaccinated children refuse additional vaccines. Some of these parents were even rejecting boosters of the same shots they unquestioningly accepted for their children just a few years earlier.

Froehlke estimates that he has faced around 20 such parents, maybe more: a father who said he had done his own research and sent Froehlke a ream of printouts from right-wing and anti-vaccine websites to prove it; a mother (who is a nurse) who adamantly refused routine boosters for a kindergarten-age daughter — and then later, when the child got sick with Covid-19, asked Froehlke without success to give the deworming drug ivermectin to her. The overall number of these new doubters in his practice hasn’t been large, he says, but considering it was almost zero before the pandemic, the trend is both notable and worrisome.

These parents are not uneducated, Froehlke told me. Some of them are literally rocket scientists at the nearby Lockheed Martin facility. What has happened, he suspects, is that rampant misinformation related to the Covid-19 vaccines, and the fact that pundits like Tucker Carlson on Fox News have devoted a lot of time to bashing them — among other untruths, he has suggested that the vaccines make people more likely to contract Covid-19, not less — has begun to taint some people’s view of long-established vaccines. “I think we’re going to see more of this, more spillover of persons who had previously vaccinated their children and who are now not going to vaccinate,” he says.

Southern California; Savannah, Ga.; rural Alabama; Houston — pediatricians in all these places told me about similar experiences with parents pushing back against routine vaccines. Jason Terk, a pediatrician in Keller, Texas, called the phenomenon “the other contagion” — a new hesitation or refusal by patients to take vaccines they previously accepted. Eric Ball, a pediatrician in Orange County, Calif., said the number of children in his practice who were fully vaccinated had declined by 5 percent, compared with before the pandemic. He has been hearing more questions about established childhood vaccines — How long has it been around? Why give it? — from parents who vaccinated older children without much hesitation but are now confronted with the prospect of vaccinating babies born during the pandemic. Some of these parents end up holding off, he says, telling him they want to do more research. “There’s a lot of misinformation about the Covid vaccines, and it just bleeds into everything,” he says. “These fake stories and bad information get stuck in people’s heads, and they understandably get confused.”

In another part of Orange County, Kate Williamson reports seeing more reluctance in her pediatric practice. Though she notes that vaccine hesitancy is not new — doctors in relatively conservative Orange County, in particular, have weathered earlier anti-vaccine flare-ups — the politicization of the issue seems different this time. “I have this worry in the back of my mind — that we’re up against something that we have never seen before,” she says. “To have something that could be anti-science as part of a political identity and culture is very concerning.”

In Savannah, according to a pediatrician named Ben Spitalnick, many first-time parents have been asking questions about vaccines that he had not heard in the past. Two years of seeing the doubts about Covid vaccines expressed on social media, he thinks, is causing parents to question other science as well. He and his colleagues — like Williamson and Ball — inform parents that they should find other doctors if they choose not to vaccinate their children. And, he told me, a number of patients have indeed left his practice.

If this dynamic continues, it could threaten decades of progress in controlling infectious disease. The C.D.C. has registered a 1 percentage point drop in childhood vaccinations since the pandemic began. Ninety-four percent of American kindergartners were up to date with their vaccines in the 2020-21 school year, compared with 95 percent the previous year, meaning that not only have vaccinations in this age group fallen below the C.D.C.’s 95 percent target, but also some 35,000 fewer children were vaccinated that year. Ball, Williamson and Spitalnick estimate that the volume of skeptical questions has increased by 5 to 10 percent over the past three years. “It doesn’t sound big,” Spitalnick says. “But it’s an awful lot of babies. That could also get you below herd immunity."

While there is a lack of data about how widespread this newfound intransigence toward vaccines is, the possibility that it may be spreading worries nearly every expert I queried. The anti-vaccine movement is “so strong, so well organized, so well funded, I doubt it will stop at Covid-19 vaccines,” says Peter Hotez, the dean of the National School of Tropical Medicine at Baylor College of Medicine. “I think it’s going to extend to childhood vaccinations.”

Political affiliation may be an important factor behind what Froehlke and others are experiencing. Though his practice is in Jefferson County, which leans progressive, he sees many patients from nearby Douglas County, which is more conservative. (It went for Trump by more than 7 points in 2020.) And Froehlke thinks he may be seeing more newly minted naysayers than some of his peers — a couple of other pediatricians I spoke to in Denver had not seen more doubters — simply because more of his patients lean to the right politically.

David Broniatowski, an associate professor at George Washington University who studies online misinformation, says that because Covid vaccines have become so charged politically, one of the largest groups in the country, white conservatives, may have also become the most susceptible to the skulduggery swirling around vaccines. “To my mind, they are a vulnerable audience that is targeted for manipulation by a pretty small number of grifters,” Broniatowski says. “It’s a crazy scenario where a dominant demographic in the country may be the most vulnerable population right now.”

In 2019, even before the pandemic struck, the World Health Organization listed growing vaccine hesitancy as one of its top 10 threats to global health. W.H.O. officials often refer to the contagion of misinformation that foments vaccine hesitancy as an “infodemic”: mountains of incorrect and sometimes flagrantly conspiratorial information about diseases that leads people to avoid lifesaving medical practices, like the vaccines used to fight them. Now the pandemic has given anti-vaccine advocates an opportunity to field-test a variety of messages and find new recruits. And one message in particular seems to be resonating widely: Vaccines and vaccine mandates are an attack on freedom.

Although it is convenient to refer to anti-vaccine efforts as a “movement,” there really is no single movement. Rather, disparate interests are converging on a single issue. Many reject the “anti-vaccine” label altogether, claiming instead to be “pro-vaccine choice,” “pro-safe vaccine” or “vaccine skeptical.” For some, there may be a way to make money by pushing the notion that vaccines are dangerous. For politicians and commentators, the “tyranny” of vaccine mandates can offer a political rallying cry. For states like Russia, which has disseminated both pro- and anti-vaccine messages on social media in other countries, vaccines are another target for informational warfare. For conspiracy-minded private citizens, vaccine misinformation can be a way to make sense of the world, even if the explanations they arrive at are often nightmarish and bizarre.

The process of swaying people with messaging that questions vaccines is how disinformation — deliberately fabricated falsehoods and half-truths — becomes misinformation, or incorrect information passed along unwittingly. Motivated by the best intentions, these people nonetheless end up amplifying the contagion, and the damaging impact, of half-truths and distortions. “This is a deadly movement,” Peter Hotez told me. “With things like terrorism and nuclear proliferation, we have lots of infrastructure. For this, we don’t have anything.”

Photo illustration by Jamie Chung for The New York Times

In 1904, the U.S. Supreme Court heard the case of Henning Jacobson, a Swedish immigrant and minister who refused to comply with a vaccine mandate in Massachusetts. He had been fined $5, equivalent to about $170 today. At issue was how much control states had over residents’ bodies. It was part of a fight that stretches back to the very first vaccine mandates, in the 19th century, and the backlashes they inspired. The arguments against mandatory vaccination then were similar to those we hear now: Vaccines are dangerous; they kill children; they infringe on personal freedom. The remarkable constancy of these claims over time is due, in part, to the fact that vaccines raise legitimately complicated and enduring questions about how much autonomy any individual should surrender for the greater good and how to apportion risk between individuals and society. In Jacobson’s case, the court ultimately ruled that states did have the power to mandate vaccination when public safety was threatened — but not if individuals could show that the vaccine would harm or kill them.

In the early 20th century, as improvements in sanitation blunted the spread of many diseases, public-health authorities moved away from outright mandates to policies of persuasion. Vaccine science accelerated, too. When the polio vaccine became widely available in 1955, it helped children avoid the frightening paralytic conditions caused by the virus, including the loss of the ability to breathe. A decade later, scientists licensed a vaccine for the measles virus, which was still sickening tens of thousands yearly and killing hundreds. In 1980, the World Health Organization declared that the smallpox virus, which kills up to 30 percent of the people it infects, had finally been eradicated through vaccination. Today, childhood infections that were often fatal or disabling as recently as the mid-20th century — diphtheria, rubella, whooping cough, measles, mumps, polio — very rarely cause deaths in the developed world. Such public-health successes are why some scientists regard vaccines as the single greatest medical advance in human history.

But that very triumph has, paradoxically, hindered the effort to counter vaccine skepticism. In the developed world, only a small portion of the population has seen the death and suffering caused by the diseases of eras past; vaccines, in the minds of many, have come to pose a greater threat than the diseases that they have helped nearly vanquish. In a sense, vaccines have become victims of their own success.

The modern iteration of the anti-vaccine movement is often traced to 1998. That February, a group of doctors and scientists held a news conference at the Royal Free Hospital in London. They had potentially incendiary findings to discuss, which were about to appear in The Lancet, a prestigious medical journal. Their paper speculatively proposed a link between the measles, mumps and rubella vaccine, the first dose of which is commonly given to children during their second year of life, and regressive autism, a mysterious condition whose prevalence seemed to be spreading. The single vaccine against the three viruses, the paper’s authors suggested, might cause an inflammatory disease of the gut, and the resulting intestinal dysfunction could affect the brain’s development. “I cannot support the continued use of the three vaccines given together,” Andrew Wakefield, the British gastroenterologist who had led the research, said. “My concerns are that one more case of this is too many.”

His words still reverberate around the world. Other skeptics had objected to vaccines over the course of the 20th century — for example, blaming the whooping-cough vaccine for causing neurological problems in children. But the medical establishment convincingly disproved the idea that the whooping-cough vaccine could lead to lasting neurological damage. By contrast, the doubts Wakefield expressed about a relatively new childhood vaccine — the combined MMR shot had been introduced in Britain only in 1988 — prompted a wave of fear about vaccines that continues to this day.

Measles immunization rates quickly dropped in parts of London, and within years, outbreaks began occurring in Britain and elsewhere in Europe. What seems to have been lost on the general public and the media was just how weak, scientifically speaking, The Lancet paper about the MMR vaccine really was. The study, which involved only 12 subjects, was so small as to render firm conclusions impossible. It had no comparison group of nonautistic children, and the subjects were not chosen randomly, a flaw in the study that could have possibly introduced significant bias into the results. At best, the paper should have been used to spur stronger studies that confirmed or refuted its speculation. Instead, many media outlets, including “60 Minutes,” treated Wakefield as one side in an ongoing scientific debate about MMR vaccine safety, when in reality there wasn’t much debate at all among most scientists.

Wakefield’s position started to unravel in fairly short order. In 2001, after he declined to conduct a larger study to substantiate or refute the contents of The Lancet study, the funding for his work at University College London dried up, according to Mark Pepys, then head of the university’s department of medicine at the Royal Free campus, and Wakefield left his job there. In February 2004, a British investigative journalist named Brian Deer began publishing what would become a series of damning articles in The Sunday Times of London and later The BMJ, formerly The British Medical Journal. His investigations revealed apparent conflicts of interest and included, among other shortcomings, evidence of what he said was scientific fraud: Medical records suggested that some of the children had developmental problems before they received the vaccines. Deer also found that Wakefield’s work had been funded by a lawyer representing parents of autistic children who thought they had been harmed by vaccines; the lawyer needed evidence to support the claim that vaccines had damaged the children he represented and had paid Wakefield to find it. The month after Deer’s first article appeared, 10 of Wakefield’s 12 co-authors from the original 1998 paper issued a “retraction of an interpretation.” “We wish to make it clear that in this paper no causal link was established between MMR vaccine and autism,” they wrote.

In 2010 — the same year that a whooping-cough epidemic in California led to the death of 10 infants, nine of them unvaccinated, and also sent more than 800 people, most of them young children, to the hospital — Britain’s General Medical Council stripped Wakefield of his medical license. He had breached medical ethics by subjecting children to unwarranted and potentially painful procedures, the council charged. Soon after that, The Lancet retracted the 1998 paper, which a British gastroimmunologist described in testimony as “probably the worst paper” ever published in the journal’s history.

In the early 2000s, Wakefield landed in Texas, where he worked for one autism-related charity and co-founded another. He still has an ardent base of supporters and, where he can find a receptive audience, gives talks about the supposed dangers of vaccines. Those appearances have included speaking to the Somali immigrant community in Minneapolis that, some years after his visits in 2010 and 2011, experienced a measles outbreak stemming from a decline in vaccinations; and video Q. and A. sessions for paying members at his film-production website.

Wakefield has also directed films such as “Vaxxed: From Cover-Up to Catastrophe,” a 2016 documentary that, along with other familiar anti-vaccine attacks, charges that the C.D.C. is hiding data showing that vaccines are dangerous. The documentary was scheduled to run in that year’s Tribeca Film Festival, which was co-founded by the actor Robert De Niro, who has an autistic son; De Niro then pulled the film after an uproar. And yet “Vaxxed” was featured on Amazon Prime’s home page for a time. It was finally removed from the streaming service after the California congressman Adam Schiff publicized its presence there in 2019. Even as at least 16 well-designed epidemiological studies by different researchers around the world, using different methods, have failed to find a link between vaccines and autism, Wakefield still contends that vaccines are dangerous and that he’s the victim of a smear campaign. (Wakefield did not respond to requests for comment made through his publisher and his film-production website.)

How did a paper with such a small sample size and an obviously weak design — a paper that was ultimately retracted — have such an outsize influence around the world? “He made news; he gave lots of press conferences,” Dorit Reiss, a professor at the University of California, Hastings College of Law, who studies vaccine policy, told me. “And the media was very supportive.” And research that could persuasively refute his contention was initially lacking, notes Daniel Salmon, the director of the Institute for Vaccine Safety at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. “It took a couple years to do studies showing that it wasn’t true,” Salmon says. “In those couple years, Wakefield traveled the world saying vaccines caused autism.”

Seven years after the notorious Lancet paper, Robert F. Kennedy Jr., son of the assassinated senator, jumped into the vaccine-autism fray. In 2005, Rolling Stone and Salon, an online publication, co-published an article by Kennedy in which he argued that thimerosal, the mercury-laden preservative used in some vaccines, was damaging children’s brains and could be driving what many had come to call the “autism epidemic.” Kennedy has said that his exploration of vaccine science that led to the article was spurred by a conversation with a mother of an autistic boy who, armed with stacks of scientific papers, persuaded him that the onset of her son’s autism coincided with his early-childhood vaccinations. He was already familiar with mercury’s toxicity from his work as an environmental lawyer.

Kennedy’s article, which opens with a description of a secretive government meeting supposedly convened by the C.D.C. where the use of mercury compounds in vaccines was discussed, had all the makings of a thriller about government malfeasance. But soon after it appeared, the article, which had been fact checked by Rolling Stone, required several corrections. Kennedy got numbers wrong. He took quotes out of context, making them seem more sinister than they really were. In 2011, after the journalist Seth Mnookin brought more attention to the article’s flaws in his book “The Panic Virus,” Salon removed the article from its site entirely.

Numerous well-designed studies have failed to support a connection between thimerosal in vaccines and autism. And the supposed link became even harder to argue for when the preservative was removed from childhood vaccines in 2001 — it remains in some versions of the flu vaccine — and the diagnosed cases of autism continued to rise. Kennedy, like Wakefield, nonetheless maintains that vaccines are dangerous. But he seems to have shifted the focus of his blame from mercury. Sometimes he faults the aluminum present in certain vaccine adjuvants, the substances designed to spark an enhanced response from the immune system. (As was the case with thimerosal, properly conducted epidemiological research has failed to support a link between the small quantities of aluminum in vaccines and any disorder.)

But Kennedy’s current position has moved away from scientific claims toward an even more unsettling assertion. Vaccine mandates and government efforts to manage the pandemic, he argues, are a form of totalitarian oppression. “We have witnessed over the past 20 months,” he said in a recent speech, “a coup d’état against democracy and the demolition, the controlled demolition, of the United States Constitution and the Bill of Rights.”

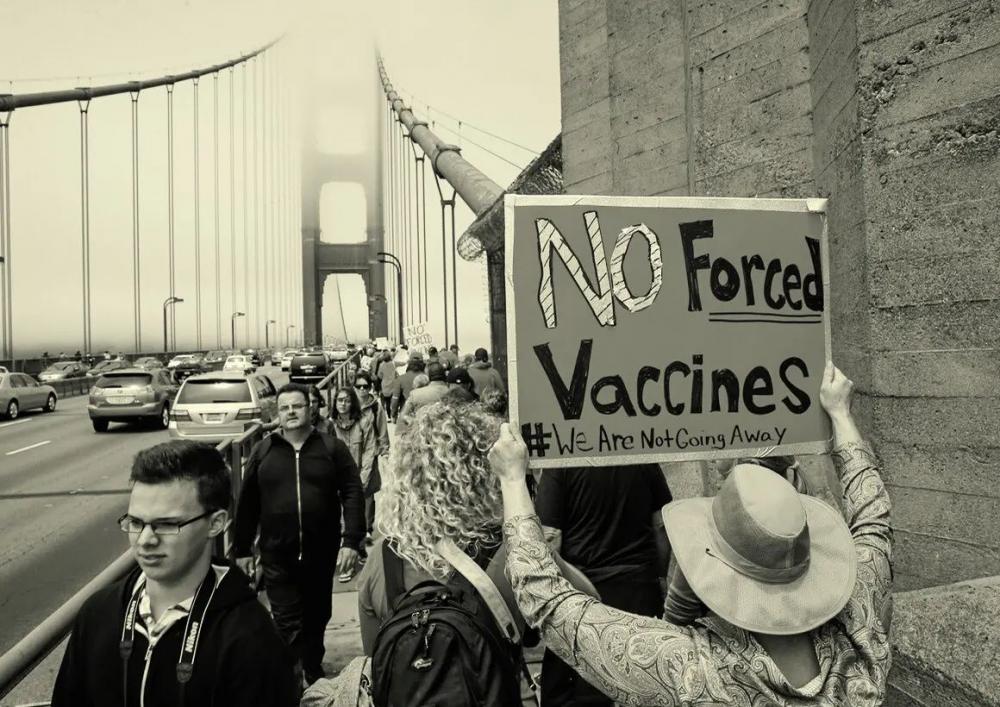

Anti-vaccine protesters in San Francisco in 2015.Credit... Michael Macor/San Francisco Chronicle, via Getty Images

In 2014, someone with measles, one of the most contagious viruses known to humanity, visited Disneyland in Orange County. Like the coronavirus, the measles virus spreads through the air we breathe. One hundred forty-seven people across the United States contracted the virus, some directly from that infected person, others from travelers who brought the disease home with them. (Additional cases linked to the California outbreak occurred in Canada and Mexico.) At least 45 percent were unvaccinated, according to the C.D.C.; another 43 percent had an unknown vaccination status — meaning many of them could have been unvaccinated as well. Although the available data is incomplete, as many as 20 percent of those who caught the measles ended up in the hospital.

Until then, California had allowed medical and “personal belief” exemptions to school vaccine mandates. Most states have some form of exemptions for reasons of personal or religious beliefs, a legacy from the 1960s and ’70s, when, as a way to mollify resistance and get mandates passed, legislators included these loopholes. A parent or pupil could say they didn’t believe in the shot and visit a doctor for counseling, and that was enough to avoid having to get it. For decades these exemptions had not posed much threat to public health: Only about 0.5 percent of Californians asked for one. But since the mid-2000s, the number of people requesting exemptions had been rising, reaching 3 percent by the early 2010s. The advent of social media and its ability to facilitate the flow of bad information may have been one factor behind this trend. Celebrities like the television personality Jenny McCarthy, who claimed that her son developed autism after receiving childhood vaccines, helped popularize the idea that vaccines could injure children. But after what became known as the “Disneyland outbreak,” state legislators tried to address what they deemed was a source of the problem by passing a bill, called SB277, that did away with personal-belief exemptions.

That was when anti-vaccine rhetoric began to shift from the idea that vaccines harmed children toward what David Broniatowski of George Washington University calls the “don’t-tell-me-what-to-do freedom movement.” It represents the moment when what had been a mostly scientific and medical argument became a political one.

Around the same time, Renee DiResta, a researcher at the Stanford Internet Observatory, a cyber-policy center where she studies online anti-vaccine activity, started seeing what she describes as a “weird libertarian crossover”: vaccine opponents networking with Second Amendment and Tea Party activists. One reason for this outreach, DiResta says, is that arguments about the supposed dangers of vaccines had proved ineffective in blocking SB277, because no good evidence supported the claim that vaccines were injurious. To keep their movement alive, anti-vaccine advocates therefore needed a new line of attack. They hoped to recruit a larger army as well.

California-based anti-vaccine groups had long used the hashtag #cdcwhistleblower on Twitter, a reference to the spurious claims of C.D.C. malfeasance that would be central to Wakefield’s conspiratorial documentary “Vaxxed.” But the hashtag only occasionally traveled beyond the confines of the anti-vaccine crowd. So different hashtags with broader appeal — #TCOT (top conservatives on Twitter), #2A (Second Amendment) and even #blm (Black Lives Matter) — were included in tweets. The tactic paid off. According to an analysis by DiResta and Gilad Lotan, a data scientist, there had not been much overlap between what they call “Tea Party conservative” and “antivax” Twitter before 2015. But around this time, a new space emerged between the two realms, a domain they labeled “vaccine choice” Twitter. Its participants were obsessed with the ideas of freedom and government overreach.

These online groups, quite small in number, proved to be very adept at leveraging the viral potential of social media to make themselves seem large. Although surveys have repeatedly indicated that the great majority of parents support vaccination, these activists fostered, DiResta says, “a perception among the public that everyone was opposed to this policy.” To her dismay, some California Republican politicians adopted this new rhetoric of “parental choice,” despite the fact that SB277 had several Republican co-sponsors. They seemed to have sensed a wedge issue, she says, “an opportunity to differentiate themselves from Democrats,” who held a majority in the Legislature. “It was pure cynicism.” Many of their own children were vaccinated, she points out. But the rhetoric galvanized people in a way that previous anti-vaccine messaging hadn’t.

Richard Pan, a pediatrician and California state senator who was one of the two lead authors of SB277, confirms that until 2015, the discourse around vaccines was basically civil. When he sponsored earlier legislation in 2012 that required people who wanted medical exemptions to visit a doctor first, the actor and comedian Rob Schneider testified against the bill, arguing that the effectiveness of vaccines had not been proved and suggesting that they caused autism. (In 2017, Schneider told Larry King that he had become more politically conservative over time and was against “any form of taking away people’s rights.”) That was basically the extent of the high-profile resistance.

But by the time SB277 was being debated in 2015, lawmakers began receiving death threats. Pan’s home address was posted online. Protesters showed up outside legislators’ offices. Some of them were closed when the staffs felt threatened by anti-vaccine protesters. And when Jerry Brown, then governor, signed the bill into law, the actor and comedian Jim Carrey tweeted, “This corporate fascist must be stopped.” (Carrey dated Jenny McCarthy for five years in the late 2000s.) “This is when things start getting less civil,” Pan told me.

In 2019, they got even worse. That year, the country experienced major measles outbreaks in under-vaccinated communities in Washington State, New York, California and elsewhere. The 1,282 documented cases were more than the C.D.C. had registered in a single year since 1992. The outbreaks were nearly enough to make the virus endemic again, meaning that after its eradication from the United States 19 years earlier, measles almost became re-established in the country.

In California, authorities had discovered that certain doctors were, in Pan’s words, “selling” vaccine exemptions — and they were making lots of money doing so. Pan sponsored a bill in response that would establish oversight of doctors who offered exemptions. Now what had been largely a campaign of online harassment started spilling into real life. He began hearing epithets with racial overtones — “Pol Pot,” “Chinese spy,” “Go home” — hurled his way. (Pan, who was born in the United States, is of Taiwanese descent.) Protesters shut down the Capitol building in Sacramento that September by screaming and chanting in the public gallery as the legislators debated the bill. Earlier the same week, while walking down the street, Pan was punched in the back by someone livestreaming the assault on Facebook. The bill was finally signed on Sept. 9, 2019, and a few days later, a woman threw a menstrual cup filled with what appeared to be blood on legislators, yelling “that’s for the dead babies!” According to Pan, in the entire history of the California Legislature — during which many contentious issues have been debated, from slavery to abortion to gun rights — no one had ever thrown anything at legislators. “So far, the only ones to do that are the antivaxers,” he says.

With Donald Trump’s arrival on the national political scene, the politicization of vaccines that was happening in California accelerated in the national arena. Figures like Wakefield and Kennedy reached new levels of visibility: Wakefield attended Trump’s inaugural ball, where he called for a “shake-up” of the C.D.C. — he has refused to divulge who invited him to the event — and Kennedy told The Washington Post that the president was considering appointing him to lead a commission on vaccine safety. Trump himself had already thrown fuel on the anti-vaccine fire. While campaigning for president, he repeated the by-then thoroughly debunked claim that vaccines cause autism. “That took this fringe issue,” David Broniatowski says, “and made it a political issue associated with the parties.”

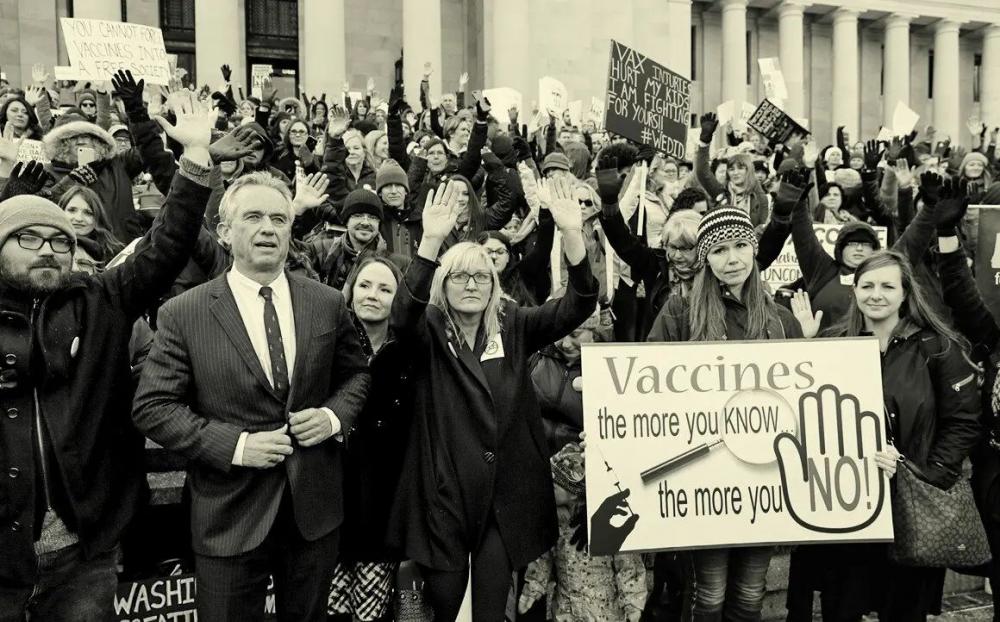

Robert F. Kennedy Jr. with supporters at the State Capitol in Olympia, Wash., where they opposed a bill to tighten measles, mumps and rubella vaccine requirements for school-age children in 2019.Credit...Ted S. Warren/Associated Press

Moises Velasquez-Manoff wrote his first piece for the Sunday Review in 2012. His work has also appeared in The New York Times Magazine, The Atlantic, Mother Jones and Scientific American. He's the author of the book “An Epidemic of Absence: A New Way of Understanding Allergies and Autoimmune Diseases.” He lives in Berkeley, Calif.

Spread the word