In it you’ll find 23 essays and interviews summarizing the experience of labor, minority, and community-based organizations during the 2020 presidential and the 2021 Georgia run-offs elections.

The authors describe the grassroots organizing that drove outreach and produced record turnout in 2020, particularly of low-income and voters of color. This turnout, they argue, must be replicated in future election cycles.

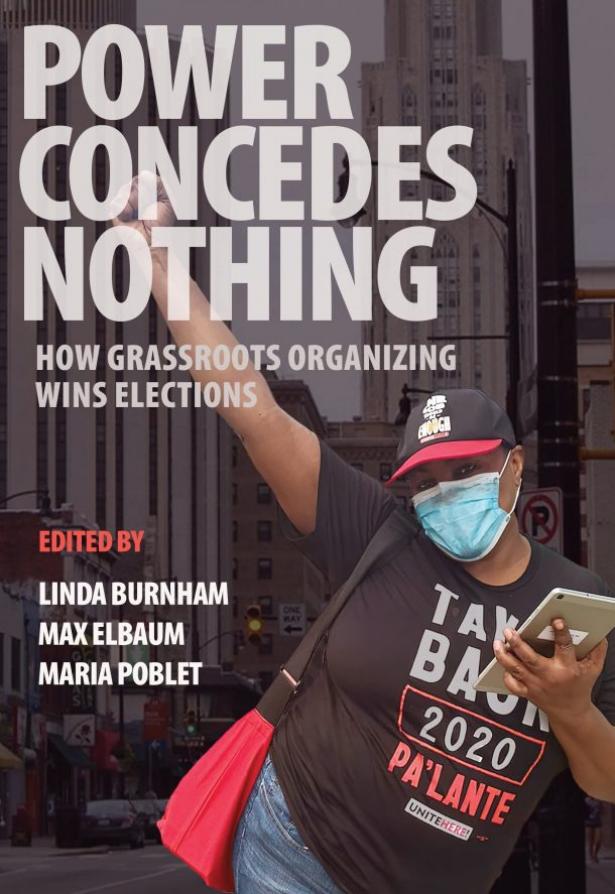

Power Concedes Nothing: How Grassroots Organizing Wins Elections

Edited by Linda Burnham, Max Elbaum And Maria Poblet

OR Books; 420 pages

September 20, 2022

Paperback: $25.00; E-book: $12.00

ISBN 978-1-68219-330-3 -- 978-1-68219-329

Editors Linda Burnham, Max Elbaum, and Maria Poblet, all experienced organizers and strategists, contend, “We are in the early stages of an era in which the left strengthens its capacity for effective intervention from one election to the next, shifting the political alignment in a progressive direction.”

By combining short-term electoral organizing “on the doors, in union halls, places of worship, schools, and community centers” with long-term social justice organizing, base building, and leadership development, the Left can play an essential role in the struggle against oligarchy and white supremacist minority rule while advancing enduring structural change.

The book includes case studies of 2020 electoral organizing in swing states such as Georgia, Nevada, Arizona, Pennsylvania, Florida, Virginia, Michigan, and Texas. Other chapters analyze the nationwide electoral work of organizations such as UNITE HERE, Seed the Vote, People’s Action, the National Domestic Workers Alliance, Democratic Socialists of America, and the Win Justice Coalition. Several chapters consider the work of organizations engaging black, Latinx, Native American, and Asian American/Pacific Islander (AAPI) voters in multiple states.

Each chapter emphasizes that years of grassroots electoral and social justice organizing preceded the 2020-2021 Democratic victories. The lessons for future elections are too numerous to discuss in this essay. However, four takeaways stand out for this reviewer.

First, there is no contradiction between local, state, and federal electoral work and the day-to-day patient work of building a long-term social and economic justice movement. UNITE HERE is a labor organization representing hotel, food service, and gaming workers that hit the doors early in 2020 with 1700 canvassers, adhering to strict COVID protocols in the swing states of Nevada, Arizona, Florida, and then later in Pennsylvania. The union is a powerhouse in Nevada, and many observers credit UNITE HERE with flipping the Silver State from deep red to nearly blue. “LOAs” or leave-of-absence workers are the foundation of the union’s political success. The union negotiates with employers to allow workers to leave the workplace to walk precincts as paid union canvassers. After the elections, LOAs return to the workplace with the same pay, benefits, seniority, and job classification.

LOAs receive extensive on-the-job supervision and training to win the election and develop their leadership skills. The goal is not just to make LOAs better canvassers but for them to become more effective committee members, shop stewards, or staff organizers when they return to work. As UNITE HERE staffer Stephanie Greenlea stated about 2020 LOAs, “Their growth was immense – through the struggle, they completely bloom.”

Second, door knocking is the essential ingredient for winning close elections. All the organizations profiled in the book testify that the face-to-face conversation at the door is the most effective and efficient way to reach out to and turn out voters – particularly low propensity or infrequent voters such as youth, immigrants, and voters of color.

Canvassers must reflect the racial composition of the turf they walk, which often requires multiple house visits and outreach through community and faith networks. Enlarging the electorate by mobilizing these voters – whose politics are to the left of mainstream Democrats – is critical for progressives and the future of the Democratic Party.

In 2020, according to Brookings Institution demographer William Frey, lower propensity voters – along with higher propensity voters in racially diverse suburbs – were the slender margin of difference for the Biden-Harris ticket in six battleground states where Democrats won by less than 3%.

Seed the Vote (STV) is an organization formed in 2019 by organizers affiliated with Bay Rising, an alliance of San Francisco Bay Area organizations. STV partners with organizations such as UNITE HERE, LUCHA (Living United for Change in Arizona), and New Georgia Majority to place in swing states—often on short notice–seasoned California volunteer organizers and STV-trained novice canvassers and phone bankers.

After deploying 1270 volunteers to Georgia, Arizona, and Pennsylvania in 2020-2021 STV leaders concluded that “traveling and taking time off in the pandemic was not easy for anyone, but once people started knocking on doors, they did not want to stop” and that “we must stick to door-to-door and in-person tactics that are at the root of our people power.”

Third, as editor Maria Poblet points out, mobilizing low-propensity voters for a given election cycle is insufficient. Grassroots electoral organizing must move these voters to become high propensity. Electoral organizing must connect these voters to year-round voter education and local campaigns that relate directly to their needs, such as winning voting rights for formerly incarcerated people, raising the minimum wage, union organizing, rent relief, and eviction protection. Lower propensity voters who become active during elections must find an enduring political home with labor and community-based groups organizing for the long haul and building power at the local level.

Finally, a section of the book analyzes the fraught relationship between social justice progressives and the Democratic Party. “Bernie 2020: Not Me, Us” is a roundtable discussion of organizations that supported Sanders. The chapter concludes that the 2016 and 2020 Sanders campaigns “succeeded in surfacing and building a progressive force both inside and outside the Democratic Party, pushing the center of the Party leftward while at the same time helping build forces outside the party willing to work in coalition.” Sanders’s enduring influence is evident in how many of his policy priorities have moved from the margins to the Democratic Party mainstream.

Maurice Mitchell from the Working Families Party (WFP) urges a “dual election strategy” of coalition with the Democrats against the neo-fascist and right-wing authoritarianism of the Republican Party while simultaneously supporting progressive Democrats who challenge the Democratic establishment. He points to the WFP support for progressive Jaamal Bowman, elected to Congress in New York’s 16th Congressional District in 2018, as an example. Mitchell stresses the importance of the WFP efforts to expand the Democratic voter base by reaching infrequent voters, building an independent electoral infrastructure, and supporting down-ballot progressive state and local candidates who run on the WFP’s “People’s Charter” platform – a comprehensive left agenda for structural change.

At the presidential level, WFP supported Bernie Sanders in the primary in 2020 but then pivoted to Joe Biden in the general election. For WFP, the presidential election “was a door and not a destiny.” It was essential to coalesce with Democrats and progressive organizations in a united front against Trumpism. Yet simultaneously, the WFP continued to support progressive Democrats up and down the ballot, such as Jessica Cisneros in the Texas 28th Congressional district, who lost to corporate Democrat Henry Cuellar by less than 300 votes, and Kendra Brooks, the first third-party candidate elected to the Philadelphia City Council in a century.

The WFP believes that its considerable success in electing progressive state and local candidates is a stepping stone to expanding the party’s influence at the federal level.

Georgia represents another model for grassroots electoral politics within and outside the state’s Democratic Party. There, Black Voters Matter, Georgia Latino Alliance for Human Rights, New Georgia Action Fund, and Standing Up for Racial Justice Action aligned with other grassroots organizations to build upon the foundation of Stacey Abrams’s run for Governor in 2018.

Abrams’s New Georgia Project had registered hundreds of thousands of new Black, brown, AAPI, and youth voters in every county in Georgia before that election. The campaign relied upon canvassing and community networks to turn out immigrants and voters of color in record numbers despite intense voter suppression. The New Georgia Project and other grassroots organizations supporting Abrams were independently funded and staffed by experienced organizers, mainly women of color.

During the 2020 general elections and the 2021 Senate run-offs, these organizations went door to door in even larger numbers to turn out their voter base for the Democrats and local progressive candidates.

These organizations had built such a robust electoral infrastructure that they could accommodate thousands of volunteer canvassers who poured into the state. The collaboration among these grassroots organizations pushed the Biden-Harris ticket over the top in November by less than 1% of the vote. It then secured victory for Democratic Senate candidates Rafael Warnock and John Ossoff in the January run-offs. Nsé Ufot of the New Georgia Action Fund noted that “90 percent of the people who showed up to vote in November came back to vote in January.”

DSA’s experience in the 2020 primaries and general election shows the challenges of coalition politics. The organization endorsed Bernie Sanders in early 2019, followed by a “Bernie or Bust” resolution approved at its August convention. There was robust participation in the Sanders campaign by DSA volunteers from nearly half the chapters during the 2020 California, Texas, and Massachusetts primaries. Nonetheless, the Bernie or Bust resolution meant that DSA could not support Biden in the general election nor participate in the anti-Trump united front.

David Duhalde, Vice Chair of the DSA Fund, writes that the resolution “paralyzed the organization around the general election,” eroded the DSA’s credibility with allies, and increased internal strife within DSA. Duhalde suggests that since 2020, through reflection and internal dialogue, DSA has matured. According to Duhalde, most supporters of Bernie or Bust now recognize that error and are prepared to participate in a broad electoral coalition against the Right. Whether DSA will show up for the federal 2022 mid-terms remains an open question.

Progressive organizations should discuss the lessons of 2020 outlined in Power Concedes Nothing. The book is a roadmap for the midterms and beyond.

[Martin J. Bennett is Instructor Emeritus of History at Santa Rosa Junior College and a consultant for UNITE HERE Local 2.]

This is a crosspost with DSA Democratic Left Blog.

Spread the word