Eight Things You Should Know About Roberto Clemente on the 50th Anniversary of His Tragic Death

Roberto Clemente and four others died in a plane crash shortly before midnight on New Year’s Eve 1972 attempting to bring relief supplies to the victims of a massive earthquake in Managua, Nicaragua. He was 38 years old.

Great athletes come and go, and the memories of their feats usually fade with time. In Clemente’s case, his legend has only grown both inside and outside of baseball. The combination of his athletic brilliance, humanitarian ideals and tragic death at a young age made him a national hero in his native Puerto Rico and a Latin American icon. His major league career from 1955-1972 coincided with a period of dramatic social change that he embraced. Here are a few highlights from what made Clemente such a remarkable figure.

1. He came from a humble background and didn’t forget it

Clemente was the youngest of seven children who grew up in Carolina, Puerto Rico. His father, Melchor Clemente, worked on a sugar cane plantation and starting at age eight, Roberto cut cane alongside him during the harvest season. In the final television interview he gave before his death, Clemente recounted taking a job delivering large cans of milk that paid a penny a day and saving the money for three years to buy a second-hand bike. “I like people who are not big shots,” he said. “I like common people. I like workers. I like people who suffer. Because they have a different approach of life than the people who have everything and sometimes get bored.”

2. One helluva ballplayer

During his 18-year career with the Pittsburgh Pirates, Clemente won four National League batting titles and 12 Gold Gloves as the best defensive right fielder in the league. He racked up 3,000 career hits and was the MVP of the 1971 World Series. Clemente sprayed line drives across the field, ran the bases with barely-contained zeal and fielded his position magnificently. According to advanced modern statistics, Clemente’s Wins Above Replacement (WAR) of 94.8 is the 25th best for a position player in baseball history. But more than any statistic, it’s the grainy, half-century old YouTube footage.

3. Latin American trailblazer

Clemente wasn’t the first Latin American to play in the big leagues. But, he was the first to become a star and set a standard; he paved the way for the waves of great Latin American players who would follow him and transform the game.

As a dark-skinned Afro-Latino man, Clemente had to overcome racial and linguistic barriers. Early in his career, Pittsburgh sportswriters would quote his broken English phonetically (“Me heet the ball hard”) to make him sound like a baseball Tarzan. Clemente suffered a serious back injury in a car accident early in his career. He played in pain the rest of his career. When he sat out games, sportswriters implied he was a hypochondriac who didn’t want to play hurt and lacked the toughness and fortitude of his white teammates.

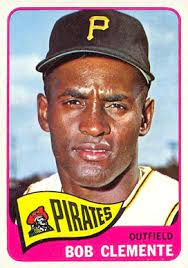

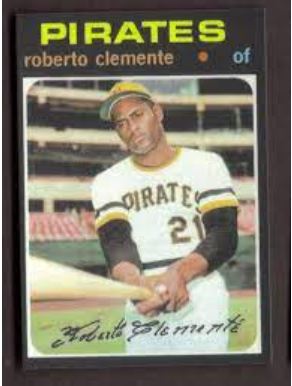

By the time this 1971 baseball card was released, Roberto Clemente had largely prevailed in his struggle to be called by his Spanish name and not “Bob” or “Bobby.”

4. Cultural pride

Clemente played in an era when Black and Latino ballplayers were expected to be quiet and grateful to have a job in the big leagues. Clemente was outspoken and always demanded respect. Sportswriters and broadcasters tried to Anglicize his name by calling him “Bob” or “Bobby” Clemente. He would respond by saying “My name is Roberto Clemente.”

Clemente’s epic performance in the 1971 World Series carried his team to victory. After the Pirates clinched the seventh and final game of the series, he was interviewed on national television. At the moment of his greatest baseball achievement with millions watching, he responded by first speaking in Spanish and thanking his parents back in Puerto Rico. It marked the first time in the United States that Spanish was spoken on national television.

5. In solidarity with the civil rights movement

Clemente was shocked when he first encountered the U.S.’s racial caste system and embraced the Civil Rights Movement. During the Pirates’ 1961 spring training in Florida, Clemente demanded that the team end the practice of making Black and Latino players wait on the team bus after spring training games while their white teammates dined inside segregated whites-only restaurants and brought them their food afterwards. Team officials backed down. They gave Clemente and his teammates of color a station wagon they could use to travel in and go to restaurants that would serve them. Clemente’s flex came about a month after a wave of lunch-counter sit-ins began in Greensboro, North Carolina and swept across the South.

Clemente and Martin Luther King Jr. became personal friends. In February 1962, King visited Clemente at his farm on the island, and the two discussed the shared struggles of Black and Puerto Rican people. When King was murdered in Memphis, Tennessee in April 1968 while aiding striking sanitation workers, Clemente was moved to act. The Pirates’ first game of the season was scheduled to be played in Houston on April 8. King’s funeral was slated for the next day and Clemente, and his Black teammates threatened to not play unless opening day was moved back to April 10 after King was laid to rest. Pirates and Astros team officials agreed to the players’ demands. Major League Baseball then headed off the prospect of more player boycotts by moving opening day back to April 10 for all teams. The players’ actions took place against the backdrop of riots in more than 100 cities and the largest deployment of U.S. troops on U.S. soil since the Civil War.

“He never spoke to me directly as to the stoppage,” his longtime friend Luis Mayoral told The Washington Post. “But we in Puerto Rico knew since it happened what he had accomplished.”

The next time professional athletes refused to play en masse in protest of racial injustice would be 52 years later in August 2020 following the police shooting of Jacob Blake in Kenosha, Wisconsin.

Speaking in his final television interview in October 1972, Clemente described King’s impact. “ put the people, the ghetto people, the people who didn’t have nothing to say in those days, they started saying what they would have liked to say for many years that nobody listened to. Now with this man, these people come down to the place where they were supposed to be but people didn’t want them, and sit down there as if they were white and call attention to the whole world. Now that wasn’t only the black people but the minority people. The people who didn’t have anything, and they had nothing to say in those days because they didn’t have any power, they started saying things and they started picketing, and that’s the reason I say he changed the whole world.”

6. Leader of baseball’s most integrated team

Jackie Robinson of the Brooklyn Dodgers broke the color barrier in 1947. By the late 1960s, the Pittsburgh Pirates were baseball’s most thoroughly-integrated team with Clemente as its leader. On Sept. 1, 1971, the Pirates became the first and only non-Negro League team in major league history to field a starting lineup in which all nine players were of African descent, mostly due to management’s willingness to seek out the best talent regardless of color in order to field the strongest possible team. Clemente played in right field that day as usual.

“The 1971 Pirates showed that you could have stars that are Black and whose clubhouse culture was rooted in accepting everyone on equal footing,” says Adrian Burgos, author of Playing America’s Game: Baseball, Latinos, and the Color Line. “That’s Clemente’s influence.”

7. Humanitarian and internationalist

As his fame grew, Clemente’s personal motto later in his life became “any time you have an opportunity to make a difference in this world and you don’t, then you are wasting your time on Earth.”

Clemente supported the Black Panthers’ free breakfast programs and health clinics. He was a magnet for children. He visited them in hospitals as he traveled from city to city during the baseball season. He put on baseball clinics for kids in the United States and Puerto Rico and dreamt of building a Ciudad Deportiva, “Sports City,” in Puerto Rico that would provide the kinds of sports facilities for the island’s youth that he never had access to growing up. He also played an important role as a mentor to his younger teammates.

“He preached like a Baptist minister,” his Pirate teammate Al Oliver recalled. “He would say, ‘How can the rich have so much (money) and there are people starving?’ This was his mindset… His spirituality.”

Clemente managed the Puerto Rican national team when it played in an international tournament in Nicaragua in November 1972. He made many friends in the country. When Nicaragua’s capital city of Managua was rocked by a massive earthquake on Dec. 23, 1972, he launched the Roberto Clemente Committee for Nicaragua. He went on national television in Puerto Rico and raised $100,000 to purchase food, clothing and medical supplies for Nicaraguan earthquake victims.

8. He was killed by greed

At that time, Nicaragua was ruled by U.S.-backed dictator Anastasio Samoza. When Clemente learned that Samoza’s troops were stealing relief supplies and reselling them on the black market, he vowed to personally deliver his aid. The DC-7 cargo plane he acquired for the mission had mechanical problems and never should have passed FAA inspection. The overloaded plane plunged into the sea off the coast of Puerto Rico shortly after take-off. Clemente’s body was never found.

“It is ironic that the profession in which he achieved ‘legendry’ knew him the least,” read a line from an obituary in The Black Panther newspaper. “Roberto Clemente was simply a man, a man who strove to achieve his dream of peace and justice for oppressed people throughout the world.”

Spread the word