As Henry Kissinger reaches 100 years of age on May 27, Chileans are preparing to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the bloody military coup that the former US national security adviser helped orchestrate in September 1973. Kissinger’s controversial career is littered with scandals and crimes against humanity: support for mass murderers and torturers abroad, domestic wiretapping, clandestine wars in Indochina, and, as Greg Grandin reminds us, secretly sabotaging the quest for peace in Vietnam. But his pivotal role in the covert US efforts to undermine democracy in Chile, aiding and abetting the rise of the infamous dictator Augusto Pinochet, will always be the Achilles’ heel of Kissinger’s much-ballyhooed legacy.

The declassified historical record leaves no doubt that Kissinger was the chief architect of US efforts to destabilize the democratically elected government of Socialist Party leader Salvador Allende. Once Allende was overthrown, Kissinger became the leading enabler of Pinochet’s repressive new regime. “I think we should understand our policy—that however unpleasant they act, this government is better for us than Allende was,” he told his deputies as they reported to him on the human rights atrocities in the weeks following the coup. At a private June 1976 meeting with Pinochet in Santiago, Secretary of State Kissinger offered platitudes rather than pressure: “My evaluation is that you are a victim of all left-wing groups around the world,” he told Pinochet, “and that your greatest sin was that you overthrew a government which was going communist.”

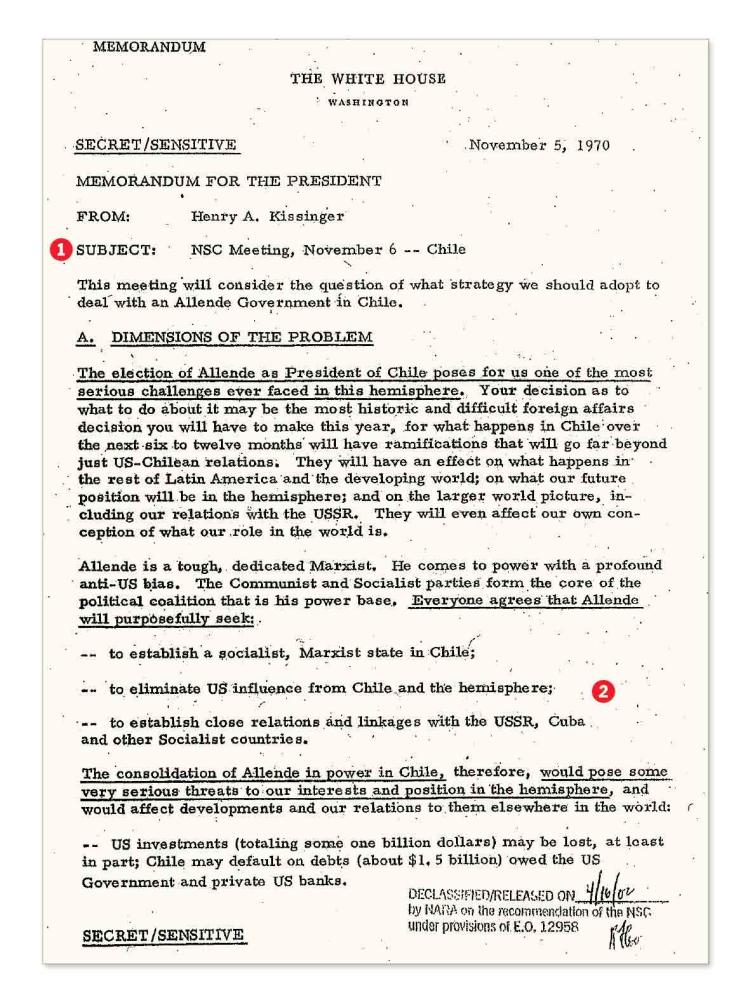

❶ Between Allende’s election on September 4, 1970, and his inauguration two months later, the CIA launched a major covert operation to block his ascendance to the presidency. Ordered by President Nixon and overseen by Kissinger, the operation—code-named FUBELT—led to the assassination of Gen. René Schneider, the pro-constitution commander in chief of the Chilean Army. But the operation failed to foment a military coup.

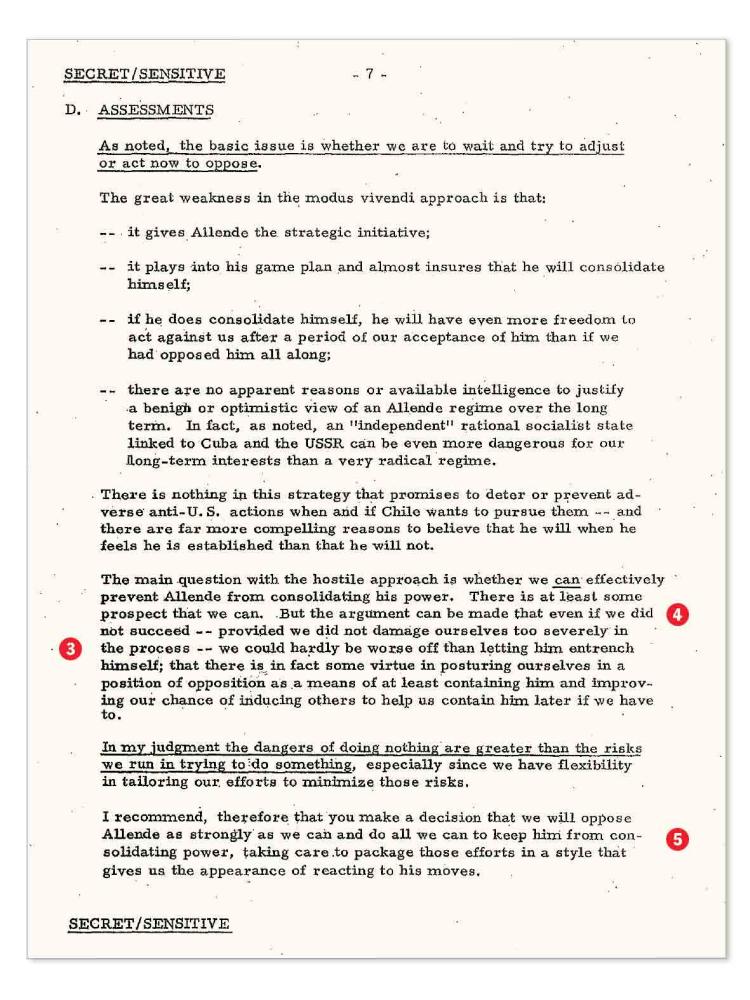

The day after Allende’s inauguration, Nixon scheduled a meeting of his National Security Council on November 5 to establish what US policy toward Chile would be. But Kissinger requested that the meeting be postponed by a day to give him time to personally present this pivotal memorandum to Nixon and persuade him to reject the State Department’s position that Washington could establish a modus vivendi with an Allende government. Kissinger lobbied the president to adopt an aggressive, if covert, effort to “oppose Allende as strongly as we can.”

❷ In his presentation to the president, Kissinger acknowledged that Allende had been legitimately and democratically elected—“the first Marxist government ever to come to power by free elections”—and would adopt a moderate position toward the United States. In Kissingerian logic, that made Allende even more of a threat. Among the rationales Kissinger presented for destabilizing Allende’s new government was one key factor: “The example of a successful elected Marxist government in Chile would surely have an impact on—and even precedent value for—other parts of the world, especially in Italy. The imitative spread of similar phenomena elsewhere would in turn significantly affect the world balance and our own position in it.” As Kissinger advised the president, “its ‘model’ effect can be insidious.”

❸ Kissinger successfully persuaded the president to approve this clandestine destabilization policy. At the NSC meeting the next day, Kissinger reiterated his arguments for intervention. “Developments in Chile are clearly of major historic importance, and they will have ramifications that go far beyond just the question of US-Chilean relations,” his talking points for the NSC meeting dramatically began. “The question therefore,” Kissinger stated after outlining the purported threats to US interests of a successful Allende government, “is whether there are actions we can take ourselves to intensify Allende’s problems so that at a minimum he may fail or be forced to limit his aims, and at a maximum might create conditions in which collapse or overthrow might be feasible.”

At the NSC meeting the next day, according to a secret summary, Nixon backed Kissinger and parroted his position. “Our main concern in Chile is the prospect that he can consolidate himself and the picture presented to the world will be his success,” the president informed his top national security managers.

❺ The objective of Kissinger’s policy of hostile intervention came to fruition on September 11, 1973—Chile’s own 9/11. Kissinger then ushered in a policy of assisting the new military regime, which would become renowned for murder, torture, disappearances, and even international terrorism on the streets of Washington, D.C.

“The Chilean thing is getting consolidated,” Kissinger informed Nixon a few days after the coup, “and of course the newspapers are bleating because a pro-Communist government has been overthrown.” “Isn’t that something,” Nixon mused about what he called “this crap from the Liberals” on the denouement of democracy in Chile. “Isn’t that something.”

Kissinger also lamented the failure of the US press to celebrate their Cold War accomplishment. As he told Nixon, “in the Eisenhower period we would be heroes.”

Copyright c 2023 The Nation. Reprinted with permission. May not be reprinted without permission. Distributed by PARS International Corp.

Peter Kornbluh, a longtime contributor to The Nation on Cuba, is co-author, with William M. LeoGrande, of Back Channel to Cuba: The Hidden History of Negotiations Between Washington and Havana. Kornbluh is also the author of The Pinochet File: A Declassified Dossier on Atrocity and Accountability.

The Nation Founded by abolitionists in 1865, The Nation has chronicled the breadth and depth of political and cultural life, from the debut of the telegraph to the rise of Twitter, serving as a critical, independent, and progressive voice in American journalism.

Please support progressive journalism. Get a digital subscription to The Nation for just $24.95!

Spread the word