Alabama Legislators Buck Supreme Court, Cling to Racially Discriminatory Voting Districts

In the 1950s and 60s, southern officials — desperate to maintain the racial status quo — regularly ignored court orders affirming the rights of Black Americans. In 1954, for example, the Supreme Court ruled in Brown v. Board of Education that racial segregation of public schools was unconstitutional. Mississippi Senator James Eastland (D) immediately declared that “the South will not abide by nor obey this legislative decision by a political body.” Virginia Governor Thomas Bahnson Stanley (D) created the Gray Commission, which was dedicated to defying Brown. Virginia Senator Harry Byrd (D) created a “Southern Manifesto," signed by more than 100 elected officials who pledged to resist implementing the Brown decision. As a result, it took continued litigation, protests, and the National Guard to even begin the integration of public schools.

But defying court orders to maintain racially discriminatory policies is not part of America's past. It is happening in 2023.

Black people account for more than one-quarter of Alabama's population. But, for decades, white Republicans have ensured that only one of Alabama's seven members of Congress is Black. They've accomplished this by gerrymandering the state's Congressional districts to limit Black voting power. The process is called "packing" and "cracking." First, as many Black voters as possible are packed into a single Congressional district. Then the remaining black voters are cracked — split into multiple districts — to limit their voting power.

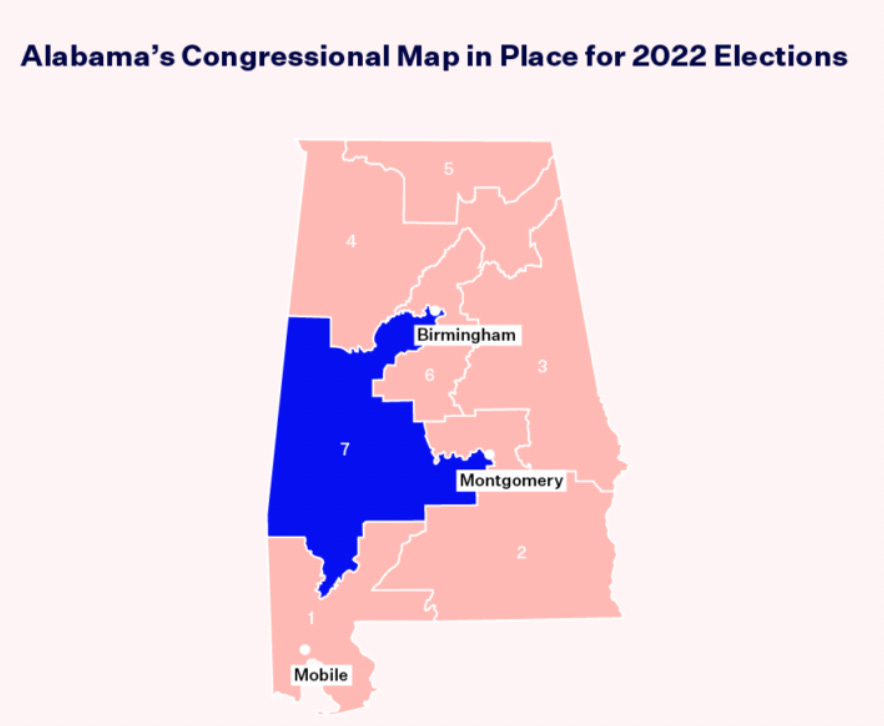

Alabama's map for the 2022 election, which is based on the 2020 Census, looks like this:

Most Black voters are packed into the oddly shaped District 7, shown in blue. Almost all other Black voters are spread out into Districts 1, 2, and 3, where they make up no more than 30% of the vote.

The map was challenged in federal court by multiple Black Alabama voters who claimed the map violated Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act. Section 2 "prohibits voting practices or procedures that discriminate on the basis of race." In making a determination about whether a map violates Section 2, the court considers a variety of factors, including "the history of official voting-related discrimination in the state," "the extent to which voting in the elections of the state or political subdivision is racially polarized," "the use of overt or subtle racial appeals in political campaigns," and "the extent to which members of the minority group have been elected to public office in the jurisdiction."

The plaintiffs won a request to block the maps in federal district court. The court found that "Black Alabamians enjoy virtually zero success in statewide elections," that political campaigns in Alabama are “characterized by overt or subtle racial appeals,” and that “Alabama’s extensive history of repugnant racial and voting-related discrimination is undeniable and well documented.”

Alabama, however, appealed the decision to the Supreme Court, which lifted the injunction and allowed the maps to be used for the 2022 election. The Supreme Court agreed to consider the case on the merits after the 2022 election, but many observers thought they would again side with Alabama officials and gut Section 2's protections against racially discriminatory voting practices.

On June 8, 2023, however, the Supreme Court rejected Alabama's maps, with Justices Roberts and Kavanaugh joining the court's three liberal justices, Kagan, Sotomayor, and Jackson. The majority opinion agreed with the district court's determination that Alabama's maps have a “racially discriminatory motivation” or an “invidious purpose.” The maps, the court found, were put into place "'to minimize or cancel out' minority voters’ 'ability to elect their preferred candidates.'"

The Supreme Court's ruling reinstated the district court's order, which required the Alabama legislature to create new maps. The district court's decision emphasized that, to comply with the law, the new maps "will need to include two districts in which Black voters either comprise a voting-age majority or something quite close to it."

The Alabama legislature has until Friday to comply with the district court's order. But the state's political leaders have chosen to pursue a different path.

Alabama produces new maps with the same problems

Alabama is on a path to approve new maps before Friday's deadline. But the new maps do not comply with the district court order and continue to dilute the Black vote. Specifically, the legislature has failed "to craft a second majority-Black district" or "something quite close to it." Instead, the new map only still includes one district, District 7, which is majority Black. It looks like this:

...

The new map, which has already been approved by committees in the Alabama House and Senate, increases the number of Black voters in District 2 from about 30% to about 38%, according to Republican legislators. The Alabama legislature has created a district that would have comfortably supported Trump over Biden in 2020 and now claims it complies with the court order. "This map and the process that led up to it are as deceitful as they are shameful," the National Redistricting Foundation, an anti-gerrymandering group, said of the new map. "This follows a pattern we have seen throughout history when it comes to redistricting in Alabama, where a predominately white and Republican legislature has never done the right thing on its own, but rather has had to be forced to do so by a court."

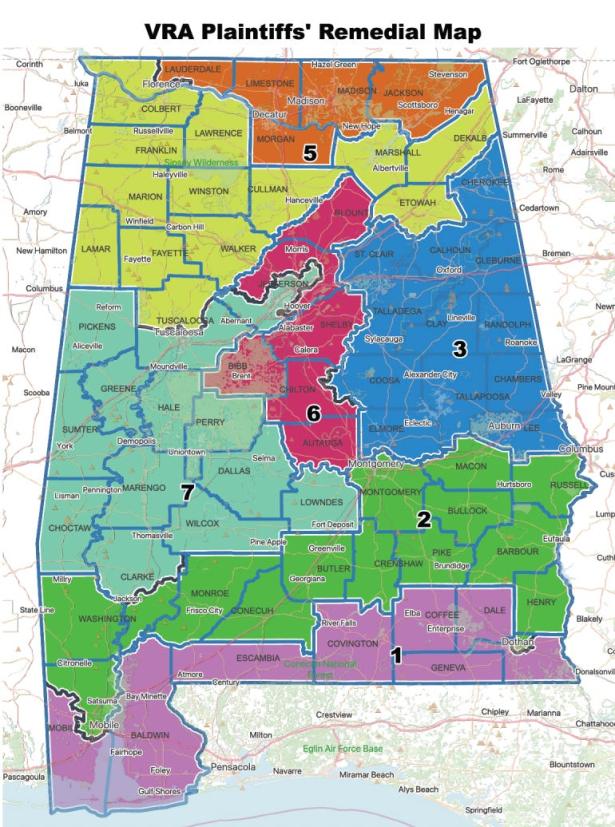

The plaintiffs in the lawsuit sent the legislature a map demonstrating how easy it was to comply with the court order. The plaintiffs' map would have a majority of Black voters in District 2, while maintaining the Black majority in District 7.

The legislature ignored this suggestion.

If the Alabama legislature stays on its current path and approves its map with only one majority Black district, it will surely find itself back in court. Alabama's leaders will have to convince the district court that the new map complies with the district court's order. But the district court just had its initial decision, which called for the creation of a second majority Black district, affirmed by the Supreme Court. So it would not be surprising for the district court to reject the legislature's new map and impose its own map that complies with the law.

[Judd Legum is founder and author of Popular Information, an independent newsletter dedicated to accountability journalism. You can reach him at judd@popular.info.]

Spread the word