Part of why we struggle to understand school shootings is because there isn’t enough data available about these extremely rare events. A recent study published in Nature Human Behavior describes a carefully curated dataset for US school shootings between 1990-2013, created from existing data and original data sources.

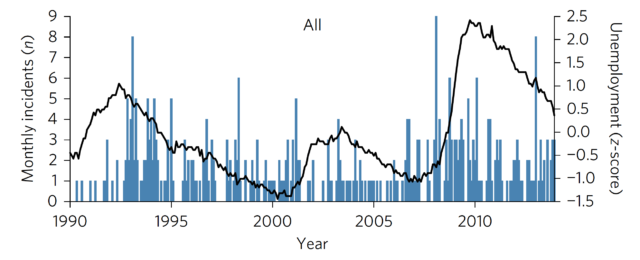

In their analysis, the authors of this paper found that the rate of school shootings increased from 2007-2013. They also found data that suggested increased shooting rates were correlated with increases in unemployment rates. This finding indicates that high levels of economic distress may lead to increases in school-related gun violence.

Previous research on school shootings has resulted in contradictory claims because there hasn’t been a single, coherent dataset. Instead, multiple datasets with different inclusion criteria have made the resulting findings difficult or impossible to compare since they analyze fundamentally different information. To solve this problem, the authors made a new collection of school shooting data, which resulted in the inclusion of almost 400 events. Their criteria for inclusion in this dataset are:

- The shooting event involved a firearm being discharged, even if by accident

- The shooting event occurred on a school campus

- The shooting event involved students or school employees, either as bystanders or victims

This last criterion is in place to exclude related gun violence that just happens to occur on school campuses, such as gang violence on playgrounds during non-school hours. The inclusion criteria do not limit shooting events to mass shootings or to those in which people were hurt or killed; the presence of incidences of attempted violence is another characteristic that makes this dataset unique.

In the first portion of their data analysis, the authors looked just at the rate of shooting events. The data showed distinct periods of time with different rates of shooting events, which suggested that some external factor might be associated with periods of increased shootings.

The authors decided to compare these periods of increased shootings with the unemployment rate because unemployment is an aggregate statistic that summarizes many economic hardships. Unemployment may summarize the hardships faced by students’ families, as well problems that older students face as they make the school-to-work transition. Strong evidence in the literature also suggests that children feel the impact of their parent’s employment status.

The authors suspected that gun violence in schools may be linked to students’ disappointment in previously held beliefs that education can improve economic opportunities. If students begin to feel that education won’t help them find economic security, perhaps this makes them more likely to lash out within the educational institution that is failing them.

In this investigation, the authors found a significant relationship between the number of shooting incidents per month and the unemployment rate. Increasing unemployment was strongly associated with decreasing time between shooting events. The authors also looked at the relationship in reverse and checked to see if times with higher shooting rates also had higher rates of unemployment. They found that months with two or more shooting events had larger mean-normalized unemployment rates.

They also dug into the regional differences in this relationship. In big cities (New York, Chicago, Detroit, Los Angeles, Memphis, and Houston), they saw that months with multiple shootings had higher regional unemployment rates. This suggests that the relationship between unemployment and school shootings may be linked closely to nuances in regional trends in unemployment, rather than an overall national sentiment.

The last 25 years have seen two periods of elevated school-based gun violence. Both of these periods were significantly correlated to increases in economic insecurity. While these findings aren’t exactly causal, the hypothesized causal relationship is a reasonable one: economic insecurity could lead people who are violently predisposed to lash out against an easy-to-access institution that is failing them: schools. With this new supporting data, the connection is worth examining in more detail.

Roheeni Saxena is a Science Correspondent writing for Ars Technica. She holds an MPH from Columbia, where she worked as Associate Director of Educational Programs. She has also worked as a bench researcher for Harvard Medical School and the NIMH. She is currently pursuing a PhD in environmental health and neurotoxicology from Columbia.

Spread the word