There’s a line that’s repeated throughout the 1987 movie Hollywood Shuffle as a sort of inside joke for black viewers who are watching: “There’s always work at the post office!” It’s a wink at a commonly uttered phrase by black people in America. But it’s also a quip with a serious material basis for black workers who have found in the US Postal Service employment stability and upward mobility for generations.

Many prominent black Americans paid the bills by working the mail as they pursued their larger ambitions. Dick Gregory worked as a postal worker in Chicago during the daytime before refining his stand-up routine at night. In between gigs, the jazz great Charles Mingus put on a USPS uniform. As he was building his career as a writer in the late 1920s and early 1930s, Richard Wright worked in the post office, and he referenced this experience in early novels. Even the famous communist Harry Haywood worked for the postal service after fighting in World War I.

For the average black worker, the postal service represents a stable, decent-paying career that is hard to find elsewhere. Today the average salary of a USPS employee is $55,000, and 21 percent of USPS employees are black. The history of black postal workers demonstrates the critical importance of government employment and a robust public sector for the advancement of black people in this country.

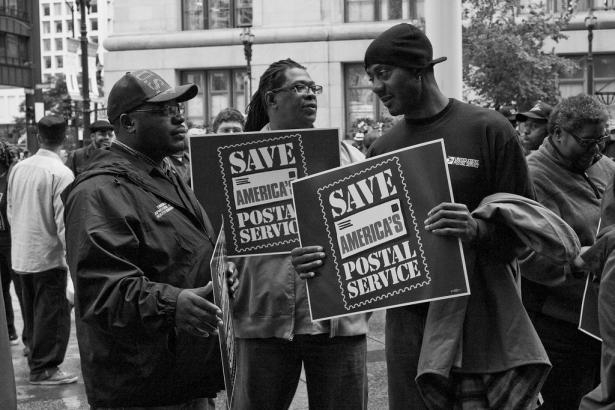

In 2019 the postal service, just like the public sector more generally, is under attack from Republicans and centrist Democrats alike. This attack represents a severe threat to the living standards of a large section of black workers and their families.

Saving and expanding the public sector will be a key fight for racial justice in the 2020 presidential race. Bernie Sanders, with his call for postal banking and robust government programs, is the only candidate offering a real plan to revive the postal service and the futures of black public-sector workers.

Origins

The story of black workers in the post office begins with the legal end of slavery and the soldiers who fought for that freedom. As early as 1861, federal employment was opened up for black workers. In December 1864, Senator Charles Sumner passed a bill banning discrimination in postal employment. Though not always enforced, this protection was critical for enabling black workers to establish a foothold in a relatively stable and secure occupation.

Many black Union Army veterans joined the postal service after the Civil War ended. Take William Harvey Carney. Carney escaped from slavery in the 1850s and eventually volunteered for the 54th Massachusetts Regiment. In 1869 he became a postal worker and served for thirty years, becoming the founding vice president of the National Association of Letter Carriers (NALC) Branch 18. The NALC itself grew out of the Milwaukee local of the Grand Army of the Republic, the national fraternal organization of Union Army veterans. Black postmasters during the Reconstruction era were seen as a threat to white supremacy because of their elevated community status and importance.

Despite the opportunities in the postal service, various forms of discrimination were still present, and blacks were prevented from working as railway mail clerks. This led to the formation of the mostly black National Alliance of Postal Employees (NAPE), which was led by college-educated intellectuals and viewed itself more as a civic organization than a labor union. This perspective led NAPE to closely ally and collaborate with the NAACP in the early twentieth century.

During the 1930s and 1940s, black civil rights activity had a decidedly working-class character and was closely intertwined with the labor movement. Black postal workers and their unions formed a crucial pillar of this black–labor alliance.

Postal workers played an important role in expanding the working-class base of the NAACP in the 1920s and 1930s. By 1940, postal workers led some of the NAACP’s largest branches in New Orleans, Norfolk, and Mobile. Chicago NAPE activist Henry W. McGee’s election in 1946 as local NAACP president represented a victory over the “silk stocking crowd” that looked down on his status as a worker and his strategy of grassroots militancy. This tactic of working-class infiltration of NAACP branches was used by many other unions at the time, like the United Packinghouse Workers of America and the United Auto Workers.

NAPE used this position to push the federal government on antidiscrimination measures for federal employees. With the help of the NAACP, they forced Franklin D. Roosevelt to get rid of the application photo requirement by executive order in November 1940, a requirement often used to screen out black applicants.

Three years later, Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9346 moved the Fair Employment Practices Commission to the Office of Emergency Management and broadened its scope to include government agencies, creating space for more antidiscrimination measures to be pushed through. It became especially important for black workers during the postwar period, as the number of black federal employees shot up to around 150,000.

The shift to unions and working-class activists taking the lead on civil rights issues was a dramatic change to the ideology of what black leadership was supposed to look like. Historian Martha Biondi explains, “In an era when unionized blue and white-collar employment was becoming a stepping stone to a middle-class lifestyle, autoworkers and meatpackers, nurses and postal workers, displaced the ‘talented tenth’ as agents of black community advancement.”

Federal Action

A common theme throughout black history has been the importance of an activist federal government for advancing fundamental interests. Postal workers utilized executive orders in particular to improve their situation in the 1960s. This activism and the resulting legislation created a home for black women workers in the post office as well.

Among the few highlights in John F. Kennedy’s lackluster record on civil rights are his executive orders related to federal employment. Executive Order 10925 was issued in March 1961 and banned discrimination by employers and unions in federal contract work, followed by Executive Order 10988, which provided limited collective bargaining rights for federal employee unions that didn’t practice racial discrimination. These orders came after intense lobbying pressure from NAPE and the Negro American Labor Council.

The Equal Pay Act of 1963 was a key factor in helping black women find work in the post office in large numbers. For many black women, federal employment was a refuge from the highly unfavorable conditions that confronted them in the private sector. A monthly newsletter from the Manhattan-Bronx Postal Union in 1966 described the situation: “It is important to note that most of the women coming into the Post Office are Negroes. Reflecting conditions in the American economy and the unfair treatment that they have received on the outside down through the years, these women come into the Federal government hoping that they will get a fair shake.”

In fact, the post office was one of the only federal civilian agencies that saw an entry of large numbers of blacks and women during the Kennedy administration. Many black postal union activists went on to become active in the campaign to pass the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Special praise was given to Title VII, which made equal employment opportunity the law of the land. Fittingly, Martin Luther King Jr was the featured speaker at NAPE’s 1965 Los Angeles convention. Black postal workers recognized that, as federal employees, it was their job to force the federal government to act in their interests.

USPS Under Siege

As early as 1971, changes were being made to the postal system that disproportionately hurt black workers. After the 1970 Postal Strike, postal facilities were relocated to suburban areas in an effort to diffuse militancy. Black postal workers bore the brunt of this job loss, as NAPE vice president Wesley Young explained at the time. “The postal service has long been a place where Negroes who were denied jobs in the private sector could earn a decent living. But with the loss of this many jobs, you’ll just about break the back of the black middle class.”

Today the threats to the USPS go beyond the movement of jobs to the destruction of the system as we know it. William Burrus, the first black president of the American Postal Workers Union, said that destroying the postal service will “put an end to the relationship between people of color and their opportunity to climb up the ladder of success in our country . . . The post office has permitted millions of African-Americans to better themselves.”

In 2006, Congress passed the Postal Accountability and Enhancement Act. This act manufactured a financial crisis by forcing the Postal Service to pre-fund all retiree health care costs seventy-five years into the future, even for workers not yet born. No other company or government agency has to abide by such a law. This alone has robbed the USPS of an estimated $5.6 billion over a ten-year period. Clearly this is part of a broader plan to privatize the Postal Service and attack the living standards of postal workers. Privatizing will only lead to reduced services and higher prices, as happened in the UK when the country privatized its postal system in 2015.

A Sanders Presidency and the Public Sector

Today, one in five black workers is employed in a government job. The slower recovery for blacks in the labor market is partly due to federal job cuts. For many black workers, public sector employment represents the thin line between a decent living and debilitating poverty. In 2000, the median income of black men who worked full time in the public sector was 15 percent higher than those who worked full time in the public sector. For black women, it was 19 percent higher. Good Postal Service jobs are ones we can’t afford to lose.

What does all this have to do with Bernie Sanders? He is one of the only candidates who puts saving the USPS high on his agenda and champions reforms like postal banking.

As Sanders puts it, “Post offices exist in almost every community in our country. There are more than 31,000 retail post offices in this country. An important way to provide decent banking opportunities for low-income communities is to allow the U.S. Postal Service to engage in basic banking services.” And beyond increasing revenue and employment for the USPS, this measure would eliminate the prevalence of payday loan centers that prey on poor communities of color.

As a senator, Sanders has concrete legislative victories to his name. He fought the recent wave of post-office closures and led the successful effort to pass a Senate resolution restoring service standards. Additionally, he blocked privatizers and payday-lending-industry lobbyists from being on the postal board of governors.

Sanders’s record led the American Postal Workers Union (APWU) to endorse Bernie in 2016. APWU president Mark Dimondstein described Sanders as “a true champion of postal workers and other workers throughout the country. He is a fierce advocate of postal reform to address the cause of the USPS financial crisis, an outspoken opponent of USPS policy that degrades mail service.”

Sanders’s program would materially improve the lives of black Americans and strengthen old policies that already have. His agenda would vastly expand federal employment and create new federal programs that would disproportionately benefit workers of color. A Sanders presidency would also embody the kind of activist government that has instituted far-reaching reforms for black people in the past. He has a clear-eyed sense of the hostile Congress that would await him, and he is more likely to push through radical executive orders to fulfill his agenda.

The history of black workers in the Postal Service shows the kind of program that can transform African Americans’ lives. A Bernie Sanders presidency would strengthen and expand that program, tying a service that all Americans need and use to the improved material conditions in the lives of the black workers who hold these jobs.

Paul Prescod is a middle-school social studies teacher and member of the Philadelphia Federation of Teachers.

Jacobin is a leading voice of the American left, offering socialist perspectives on politics, economics, and culture. The print magazine is released quarterly and reaches 40,000 subscribers, in addition to a web audience of 1,500,000 a month.

Spread the word