Although Democrats rallied in the midterms and off-year elections, winning back the U.S. House and flipping 10 state legislative chambers, a series of voting restrictions enacted by right-wing legislators in key states helped ward off a genuine blue wave, particularly in the gubernatorial elections in two large Southern states.

“Let’s say this loud and clear—without voter suppression, Stacey Abrams would be the governor of Georgia, and Andrew Gillum is the governor of Florida,” U.S. Senator Kamala Harris, a candidate for the Democratic presidential nomination, told an NAACP gathering in Detroit on May 5. Harris’ remarks addressed two 2018 races lost to Republicans by narrow margins; the Georgia race was overseen by Brian Kemp, who was then Georgia’s secretary of state—and Abrams’ opponent in the gubernatorial race.

Voter-suppression measures have been spreading like viruses from state to state throughout the decade since Barack Obama became the first African-American president. The means and methods range from voter ID laws to purges of voter registrations and worse. A recent report from the Brennan Center for Justice found that between 2016 to 2018, 17 million voter registrations had been purged from the rolls. And that’s just one method of voter suppression currently in use. In Tennessee, an African-American voter registration effort was effectively criminalized by legislative action. In Florida, a voter referendum restoring rights for formerly incarcerated citizens was undercut by Republican lawmakers who limited its scope—while also passing a law designed to cut down on student voting. In Texas in 2018, a precinct at Prairie View, a historically black university where students have long struggled to exercise their franchise, had its early-voting hours cut back to fewer than half of others in the area. “Here we go again,” student Jayla Allen later recalled thinking when she heard the news.

The GOP push to restrict the franchise began in earnest after the backlash mid-term elections of 2010, when Tea Party landslides gave the party control of state legislatures across the South and industrial North. While Republicans set to work perfecting the age-old art of gerrymandering, creating artificial advantages in congressional and state legislative elections by rigging districts in their favor for the duration of the decade, they were also busy concocting new barriers to voting for the likeliest Democratic voters: African Americans, Latinos, and young people.

The purpose of these efforts was made clear decades ago, when Paul Weyrich, co-founder of the Heritage Foundation and the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC) addressed a major gathering of religious fundamentalists and said, “I don’t want everybody to vote,” adding, “our leverage in the elections quite candidly goes up as the voting populace goes down.” In 2016, Jim DeMint, then president of Heritage, was just as frank, telling a St. Louis radio host, “in the states where they do law voter ID laws you’ve seen, actually, elections begin to change toward more conservative candidates.”

Republican lawmakers in 19 states have passed new measures to suppress votes since 2017. And with so much at stake in 2020—not just the presidency and control of Congress, but the balance of power in state legislatures that get to draw new district lines for a new decade after the U.S. census—they’re not done yet, especially in the presidential battlegrounds. In 2016, voters in 13 Republican-run states had new rules to navigate when they went to the polls. Several, not surprisingly, were presidential battlegrounds like Wisconsin and Ohio. But most were states like Indiana, Mississippi, or Texas, where Republicans held statewide power, but where urban areas were becoming progressive strongholds with clashing priorities. With so much hinging on the outcome of 2020 elections—not just the presidency and perhaps democracy itself, but control of Congress, state governments, and redistricting for a decade—the pace of the efforts to suppress the vote, and the desperation to defend it, will only accelerate in 2020.

Click here and scroll down for county-by-county detail

NOBODY PAID MUCH ATTENTION last summer when an upstart group called the Tennessee Black Voter Project began dispatching canvassers across Memphis, Nashville, and countless small towns to register voters for the midterm elections. After all, few states are as deep-red as Tennessee, a one-time Democratic bastion in the South where Donald Trump bested Hillary Clinton by a margin of more than 25 percent in 2016. A decade’s worth of voter-suppression tactics, including mass purges of mostly black voters from the rolls and a Voter ID law that made it impossible for many college students to vote, has seemingly convinced many Tennesseans to the left of Trump that voting is no longer worth the bother. The state ranked 50th in turnout in 2016, and a sad 45th in voter registration. A band of millennial African Americans with clipboards and pens would surely be powerless to change that state of affairs.

AP Photo/Jonathan Mattise

But organizers like Tequila Johnson, co-founder of the civil rights group The Equity Alliance and manager of the Black Voter Project, saw “both a need and an opportunity,” she told me. They’d seen what happened when black voters had been fully engaged in Alabama the previous December, boosting Democrat Doug Jones to a shocking win in a U.S. Senate special election, and they knew that Stacey Abrams’s New Georgia Project was registering hundreds of thousands and threatening to upend the politics of one of Tennessee’s near neighbors. They also knew that even though people weren’t voting, they certainly weren’t happy and content; as Republicans accrued near-absolute power over the last decade, they’d moved one of the South’s traditionally moderate states further and further to the right, even gutting the state’s popular and progressive health-care program, TennCare.

“People look at Tennessee and say, ‘It’s red and it’ll never change,’” Johnson says. “The state actually hasn’t been red for all that long, but people increasingly thought, ‘my vote doesn’t matter,’ and our Democratic Party has not done a good job of outreach. But people are suffering from these right-wing policies. And millennials like me, including in rural parts of the state, are more open to change and accepting differences than the generations before us.”

So the Black Voter Project got to work. Canvassers set up shop outside church services, jails, and courthouses; they snagged grocery-shoppers and signed up club-goers; they went to housing projects and “100-percent immigrant communities,” as Johnson says. By October, they’d submitted more than 90,000 registration forms to stunned election officials, mainly in Shelby County (Memphis) and Davidson County (Nashville). The new voters weren’t enough to tilt the balance of power statewide, but black turnout soared—from 31 percent in 2014 to 45 percent in 2018—and helped Democrats recapture a majority on the Shelby County Commission while ousting a Republican county mayor and sheriff. In Nashville, where turnout nearly doubled from four years earlier, new voters helped pass a ballot initiative to create a community oversight board for police.

Johnson knew what to expect next. “We weren’t naive enough to think that our voter-participation numbers had happened by mistake,” she says. Tennessee had recently reduced early-voting periods and required proof of citizenship at the polls. “We knew it was by design. For us to be radical enough to say, ‘We’re gonna register people,’ for us to be bold enough to call ourselves the Tennessee Black Voter Project—we knew there would be a push-back.”

Sure enough, when Republican lawmakers convened in Nashville this winter, they were determined to snuff out this “radical” voter-registration effort in its infancy. Citing inflated figures of erroneous forms submitted, implying that mass voter fraud was underway, and echoing complaints by overwhelmed county election officials, Republican lawmakers like Rep. Mike Carter called the Black Voter Project a “debacle,” claiming that it had somehow prevented “honest voters” from being able to cast their ballots.

In April, Tennessee’s GOP majority passed a sledgehammer of a bill, making it a crime for groups with paid canvassers (as opposed to volunteers) to submit incomplete or inaccurate registration forms: Up to $2,000 in fines will be assessed for each county where an organization submits more than 100 deficient forms, and up to $10,000 if the number exceeds 500. Organizers also face criminal sanctions if they don’t attend training sessions run by local officials, or if they fail to mail in voter-registration forms within 10 days—a short window by most states’ standards. (A lawsuit against the measure, which has kept it from being enforced thus far, continues to move through the courts.)

While other states have imposed regulations on voter-registration drives, there’s never been anything like this law. For Black Voter Project co-founder Charlane Oliver, the upshot was plain to see: “They don’t want black people to vote.”

Cliff Albright, co-founder of Black Voters Matter, which works to engage African Americans in the South and assisted the Tennessee project in its start-up phase, says the Republicans’ aim was to keep voter-registration drives small and localized. “They know it’s very hard to do large-scale voter operations without paying canvassers. You can’t make a dent in a state like Tennessee with some mom-and-pop organization that relies on volunteers. The people who wrote this legislation don’t mind ad-hoc efforts. But they don’t want to see 90,000 people registered in one cycle.” The legislation, he says, will make it harder for groups to sign up paid canvassers going forward. “People will be reluctant to take that chance,” he says. “It’s intimidation, period.”

Voting-rights advocates fear that the Tennessee law will—if it survives court challenges—likely spread to other Republican-controlled states, perhaps in time to put the clamps on voter-registration efforts in presidential battlegrounds heading into the 2020 elections. “Republicans are using the state as a testing ground,” Johnson says. “Let’s test this out in Tennessee, see if it flies—and if it’s found constitutional, watch it spread to 15 or 20 more states.”

IN 2013, THE U.S. SUPREME COURT swung open the voter-suppression floodgates by invalidating a key section of the Voting Rights Act in Shelby County v. Holder. Since 1965, states and municipalities with histories of discriminatory voting laws had been required to run any changes in their elections by the Department of Justice before enacting them; after Shelby, they had free rein. Justice Ruth Bader Ginsberg predicted in a scorching dissent that the ruling would result in a resurgence of Jim Crow-style voter suppression laws, and she’s been proven sadly prophetic. In short order, 25 states turned back the historical clock—after decades in which voting laws had become steadily more liberal—by passing restrictive voter-ID laws, cutting back on early voting (which voters of color tend to use more than whites), and closing polling places in minority neighborhoods.

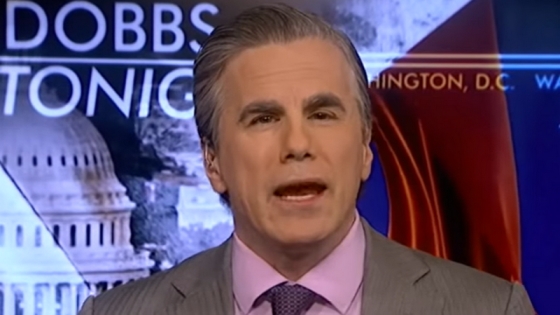

Screenshot: Fox Business Channel

The justification offered was always the same: Right-wing groups claim they simply want to combat widespread “voter fraud” and return “integrity” to American elections. President Trump’s claim of “millions” of illegal voters in the 2016 election—supposedly denying him a popular-vote victory—has been echoed repeatedly by right-wing groups like Judicial Watch. In 2017, the group’s president, Tom Fitton, told a gathering of the anti-immigrant Remembrance Project that “we had about one-and-a-half million illegal votes in the last election,” and that “about 80 percent vote for Democrats,” meaning that “one point one million voted for Hillary Clinton.” In “Rigged,” a documentary about voter suppression, Michael Hyers of the right-wing Voter Integrity Project in North Carolina, which has used a Jim Crow-era law to challenge the eligibility of thousands of voters of color in the state, captured the spirit of the movement all too colorfully: “It’s about time we turn on the lights and start cleaning the cockroaches out of here.”

Voter suppression paid spectacular dividends in 2016. Multiple studies have shown that Donald Trump would not have won the presidency without racially biased election laws that sprang up post-Shelby, particularly in the six big states that went from voting for Obama in 2008 to backing Trump—Florida, Michigan, North Carolina, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin. The tilt was most dramatic in the last of those states: After a strict voter-ID law passed the GOP-controlled Wisconsin legislature, turnout in Milwaukee, where 70 percent of black Wisconsonites live, plummeted from 74 percent in 2012 to 55 percent in 2016, while statewide, Latino and Asian voting went down 6 percent. That was enough to give Trump a nail-biting and decisive victory. Nationwide, only 59 percent of eligible African Americans voted in 2016, after 66 percent had turned out in 2012—a number that couldn’t simply be explained away by problems with Hillary Clinton’s campaign.

Republicans have come to depend on voter suppression to hold back Democrats in both the Rust Belt and the South, where demographic changes are eroding the white GOP’s decades-long dominance. But voting-rights advocates have started to fight back, with measures to expand voting rights in new ways—and counter the right’s continuing push to curtail them.

Last November, even as Trump acolyte Ron DeSantis was edging out Democrat Andrew Gillum in the race for governor of Florida, voters in the ultimate battleground overwhelmingly passed an amendment to the state constitution that looked like a death blow to Trump’s chances of carrying the state a second time. Nearly 65 percent voted for a ballot initiative that would restore voting rights to people convicted of felonies who’d served their time. Florida had become an outlier in recent decades, one of just four remaining states (along with Iowa, Kentucky, and Virginia) that still barred people convicted of felonies from voting, even after they returned to society. The law had been on the books since 1868, when Florida lawmakers—forced by the federal government to allow African Americans to vote—had devised it as a way to prevent them from gaining power, in tandem with post-Civil War laws that made black men easy to incarcerate.

Photo: Rogelio Solis/AP/Shutterstock

Now that this vestige of Jim Crow had been erased by popular demand, the number of newly eligible voters would be staggering: Estimates ranged from 1.4 to 1.6 million, including one-fifth of the state’s voting-age African Americans. When this legion of formerly disenfranchised Floridians began registering to vote in January, the state’s newspapers and newscasts featured heartwarming stories about folks like Delmus Calloway, who’d served six years on drug-possession charges and then, upon his release in 2007, turned his life around, becoming director of public works for the small city of Gretna. “This right here makes me feel like I am part of society,” Calloway told the Tallahassee Democrat. “Today is a great day for me. It’s an honor.”

But the prospect of all these new voters did not warm the hearts of Republican lawmakers. At DeSantis’ urging, they attached strings to the amendment—big, knotty strings. After months of raucous debate, they voted to allow only those who’d paid off all the fees, fines and surcharges attached to their sentences to become eligible to vote. Considering that Florida is a national leader in racking up those financial penalties, this meant that only a fraction of those who had completed their sentences would likely ever be able to exercise their franchise. The state assesses more than 115 different fines against defendants—and unpaid court charges after 90 days are handed over to private debt collectors, who can add a surcharge of up to 40 percent to the fines and fees incurred by the those so convicted.

“What this bill does is reestablish a poll tax,” said Micah Kubic, executive director of the ACLU of Florida. “It is not constitutional, it is not legal, and it is not right to deny people the right to vote because you can’t pay.”

As soon as DeSantis signed the bill on the final Friday in June, two lawsuits were filed to overturn what Gillum called a “nullification” of the vote last November. “We were unambiguous as voters,” he said. “We were going to be a state that didn’t judge people forever for their worst day.”

What the courts decide could well determine who wins Florida in 2020. The state already has a history of intolerably long urban voting lines, purges of eligible voters “accidentally” swept up in the maintenance process, worse-than-useless voting machines, and crackdowns on voter-registration groups. And if Florida’s new poll tax is upheld, it will be mighty tempting for Republican lawmakers in other states to follow suit, stripping voting rights from ex-felons who’ve already regained them.

COMPARED TO THE IMPACT of Florida’s re-disenfranchisement of so many formerly incarcerated people, some of the other voter-suppression measures passed over the last year by swing-state Republicans look like small potatoes. But they could turn out to be decisive. “Elections are increasingly so close,” notes Marcia Johnson-Blanco of the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights. “You don’t have to restrict very many people from voting to change the outcome.”

Ever since students shared some of the blame for electing Barack Obama in 2008, they’ve become particular targets for right-wing suppression efforts—particularly in states that are likely to be 2020 battlegrounds. In North Carolina, a voter-ID referendum passed last November with ambiguous wording; when Republican lawmakers filled in the details this winter, they invalidated the use of most college students’ IDs at the polls. In New Hampshire, as well, most students will also be ineligible to cast ballots; a law passed last year requires drivers who want to vote to get a state driver’s license, and those who own cars that they drive in New Hampshire to get an in-state car registration—yet another new poll tax, according to many an outraged undergraduate (not to mention older Democrats).

Student voting has long been a bone of contention in Florida. Last year, the state was forced by the courts to allow early voting on several college campuses, thwarting the plans of Republican election officials. Nearly 60,000 students took advantage. Heading into 2020, GOP lawmakers were determined not to let that happen again: At the same time they restricted ex-felons’ voting rights, they passed a measure requiring early-voting sites to have “sufficient nonpermitted parking to accommodate the anticipated amount of voters.” Civil-rights groups said this mouthful of legal verbiage was aimed directly at colleges campuses, which typically require parking permits for their limited number of spots.

“This is not about parking,” said state League of Women Voters President Patricia Brigham, whose group has filed suit to overturn the law. Instead, she said, the measure takes aim at less-fortunate kids. “Those students with cars, they can hop in their car and go to a voting site off campus. This is about students living on campus who don’t have a car and want to vote early.”

In the emerging Southwest battleground states of Texas and Arizona, Republicans spent much of this winter and spring trying to slice away potential Democratic votes in different ways. Texas lawmakers outlawed mobile polling places, which some urban (read: Democratic) counties had been using to give voters easier access to polls. Arizona, where Democrats won a U.S. Senate seat and several statewide offices in 2018, has a rich history of voter suppression; because of its history of disenfranchising Native Americans, it was one of nine states required to “preclear” changes to elections prior to the Supreme Court’s Shelby decision. More recently, though, the state has made voting easier by, among other things, allowing voters to cast “emergency votes” on the last weekend before an election, if they found they couldn’t vote on Election Day. And during the state’s generous 26-day early voting period, voters weren’t required to show photo ID. Republicans shot down both of those progressive laws this spring. “This is their strategy,” said Democratic state Rep. Athena Salman. “This year, we’re going to chip away at this part of your right. Next year …”

Republicans still have another year to chip away at voting rights before the presidential election—a fact that gives civil-rights advocates migraines. “I’m just not as creative as the people who are trying to suppress the vote,” Johnson-Blanco says, laughing gamely. “We’re trying to play catch-up all the time.”

The pace is already picking up as November 2020 approaches. In many states, election officials will conduct purges of the voting rolls; the Supreme Court has allowed them to kick off voters who’ve skipped two consecutive federal elections, and most Republican-controlled states make use of them, sometimes failing to provide the notice (and opportunity to re-register) that the law requires.

Photo from Merrill’s Facebook page.

One of the most prolific purgers, Alabama’s Republican Secretary of State John Merrill, is overseeing his own 2020 campaign for U.S. Senate, currently one candidate in a field of Republicans vying for the nomination to run against Democrat Doug Jones. Merrill has made no secret of his desire to create barriers to Alabamians who want to vote: “As long as I’m secretary of state of Alabama, you’re going to have to show some initiative to become a registered voter in this state,” he told documentary filmmaker Brian Jenkins in 2016. Asked why he opposed automatic registration for eligible citizens over 18, Merrill said, “If you’re too sorry or lazy to get up off of your rear and go register to vote, or to register electronically, and then to vote, then you don’t deserve that privilege.”

Post-Shelby, states are free to shorten their early voting periods, and to close down more polling places where Democrats live. New laws, some inspired by the latest methods cooked up in states like Tennessee and Florida, will be passed—and most will land in the courts. With Democrats’ attempts to restore the full powers of the Voting Rights Act stymied by Mitch McConnell and the Republican U.S. Senate majority, it will be another election year marked by chaos and uncertainty for voters and local election officials alike. In some states, as in 2016, voters won’t know what kind of ID is required until a court rules in the fall. Some won’t know that they’ve been purged from the voting rolls until they arrive to vote. Some won’t know where to vote; one recent report found that 1,688 polling places have been closed since 2012. Texas alone had 760. African Americans and Latinos know they will have to wait in longer lines. Others will be reading stories about disputes, in states like Georgia, over whether votes will be counted by machine, or by paper ballots that can be recounted and audited.

This uncertainty creates what Cliff Albright of Black Voters Matter calls a “fog of confusion” around voting—an indirect form of voter suppression that might be more powerful than all the others. “Voter suppression is not just one incident, one policy at a time,” says Renitta Shannon, a Democratic state representative in Georgia. “It’s a collection of actions chipping away at voting rights. If you aren’t directly preventing people from voting, you’re sending a message that it’s going to be a hassle, or that their votes won’t count. Some people are bound to end up saying, OK, why bother?”

But voting-rights advocates, who had no way of preparing for the voting-rights backlash that followed Obama’s first victory, have begun to counter it by working to broaden voting at the same time that they’re fighting off new forms of suppression. Groups like Move Texas helped triple youth turnout in that state in 2018. In Florida, Gillum has founded an ambitious nonprofit aimed at expanding the vote dramatically, while Abrams has expanded her Georgia operation, now called Fair Fight Action, to 20 states for 2020. And though the courts continued to deliver rulings favorable to voter-suppressors—like October’s Rucho vs. Cunningham decision, in which five conservative Supreme Court justices barred federal courts from hearing partisan gerrymandering claims (as opposed to racial gerrymandering lawsuits)—the key cases aren’t all setbacks.

Shortly after that ruling, judges in North Carolina went the opposite way, prohibiting the state from using Republican maps in 2020. Meanwhile, in other states, Democrats and voting-rights groups are suing to restore lost early-voting days, including crucial weekend hours before election days. In Texas, Democrats are contesting a new law that prevents campuses from having early-voting sites. And in Tennessee, while the crackdown on voter registration groups awaits its legal fate, Black Voter Project stalwarts like Tequila Johnson continue their work to counter, if not overcome, the effects of voter suppression.

“I’m going to do it anyway,” she says, despite the potential legal jeopardy. “What would have happened if Dr. King had said, ‘I’m not going to march across that bridge in Selma because there’s a law against it’? I find it almost an obligation to pick up that torch, to push forward, regardless of what the consequences are.”

Johnson keeps 25 registration forms in her car, with a goal of having them all gone by the end of each week. “On Juneteenth, I turned in 165 registration forms that I’d gathered during the month. As I was in the grocery store, gas station, picking my child up from camp, whenever I had a conversation, I’d be like—are you registered to vote?” She laughs, then turns serious and says, “They have created in me a fire they intended to dim.”

[Bob Moser is the author of “Blue Dixie: Awakening the South’s Democratic Majority.” He reports on politics for Rolling Stone, The New Republic, and other magazines.]

Spread the word