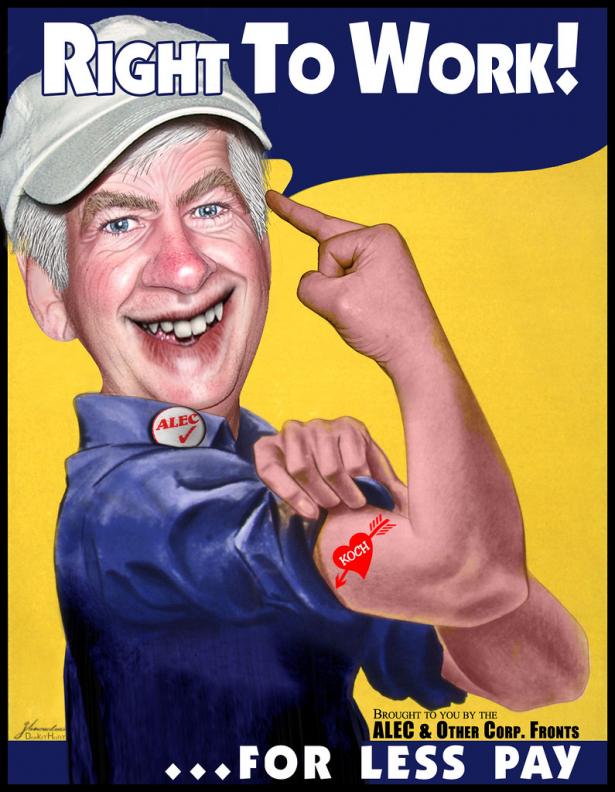

Nearly a decade ago — Dec. 11, 2012, to be exact — then-Gov. Rick Snyder landed a savage right hook to Michigan’s vaunted labor movement when he signed contentious Right to Work legislation.

Hours before Snyder signed bills that outlawed requiring workers to pay union dues as a condition of employment, 12,000 pro-union demonstrators descended on the state capitol in a tense protest that generated national media attention.

It once seemed unthinkable that Michigan, home to a powerful United Auto Workers union that organized automakers through such historic events as the “Battle of the Overpass” at Ford Motor and the Flint Sit-Down Strike at General Motors, would join mostly southern states in trying to crush labor unions.

Snyder, who once quipped that a divisive Right to Work law was “not on my agenda,” said in signing the bills that the legislation was “pro-worker” and would boost Michigan’s economy.

But nearly a decade later, there’s little evidence that Snyder’s punch staggered organized labor or sparked the state’s economy.

And now unions have a heavyweight champion in their corner. President Joe Biden, a strong backer of organized labor, wants to outlaw Right to Work as part of his effort to reinvigorate the labor movement.

University of Michigan labor economist Don Grimes said Michigan, which was once a high-income state, “looks much more like the national average” in terms of job growth, wages and per-capita income since Right to Work became law.

“My guess is that it is hard to separate out the effect of Right to Work from the impact of the downsizing of the domestic auto industry and other changes,” he told me.

Michigan State University economist Charles Ballard said prominent Right to Work supporters he’s spoken to over the years have been unable to identify any companies that have brought jobs to Michigan because of the law.

Of course, it’s not something that employers and economic developers like to brag about.

The Michigan Economic Development Corp., the state’s quasi-public business attraction agency, doesn’t even mention Right to Work (or “freedom to work,” as Republicans call it) as one of Michigan’s business climate attributes.

“My sense is that Right to Work did very little,” Ballard said.

Tim Bartik, senior economist at the Upjohn Institute for Employment Research, said he has not seen any new research contradicting earlier, national studies showing “weak evidence” that Right to Work may have created a small number of manufacturing jobs at reduced wages.

“Not a good tradeoff,” he said.

Nor has Right to Work had a big impact on union membership or weakening the political power of labor unions, which critics say was the main goal of Michigan’s Right to Work law.

The Mackinac Center for Public Policy, a free-market think tank and leading advocate of the policy, recently claimed the Right to Work law led to a “huge drop” in union membership last year.

Citing Bureau of Labor Statistics data, the Mackinac Center said Michigan fell out of the top 10 states for union membership last year “for the first time in perhaps a century or longer.”

Michigan ranked 11th in the percentage of workers belonging to a labor union last year.

Unionization rates, especially for public sector unions, have dropped since the state’s Right to Work law was passed in 2012.

Just 15.2% of Michigan workers belonged to a labor union last year, down from 16.6% in 2012. Public sector union membership fell from 54.3% of all workers in 2012 to 44.2% last year.

Government-worker unions have long been under attack in Michigan. Last year, the state Civil Service Commission ruled that state government workers must annually authorize the deduction of union dues from their paychecks.

But falling union membership is part of a trend that started long before Michigan’s Right to Work law. The annual decline in the number of union members since 1989 actually slowed after the law took effect in 2013.

And despite the Mackinac Center’s claim of a “huge drop” in Michigan union membership last year, membership grew in 2020 to 604,000 from 589,000 in 2019.

That occurred even as total state employment fell from 4.3 million workers in 2019 to 3.9 million last year, largely because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

“Our membership has been steady,” said Ron Bieber, president of the Michigan AFL-CIO, a federation of 59 labor unions representing more than 1 million active members and retirees. “It’s not as bad as [Right to Work advocates] hoped for.”

Bieber and others say Right to Work was mainly about trying to destroy the political power of labor unions to elect mostly Democratic candidates. That hasn’t happened, at least as shown by recent state election results.

In 2018, Democratic candidates took all three statewide offices — governor, attorney general and secretary of state. They picked up two congressional seats that year and kept them in the 2020 election. And they held off Republican challengers for the state’s two U.S. Senate seats in the past two elections.

Republicans control both houses of the state Legislature, but don’t credit Right to Work for that. Republicans have controlled the Senate in a gerrymandered state since 1984. Democrats have controlled the House for only six years since 1995.

Snyder was right about one thing: The state’s Right to Work law is divisive. But not much else.

Spread the word