Born in hope, 2021 expired in discouragement and depression. It looks like 2022 may be worse.

So it's no surprise that when faced by swelling inequalities, increasing racism, and growing violence against nonwhite people, some wonder whether the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s — of which I am so proud to have played a small part — is now shown to be a failure.

I understand their pain and despair, but the "Freedom Movement failed" narrative is wrong. Last week three white men in Southeast Georgia were sentenced to life in prison for the racially-motivated murder of Ahmaud Arbery a Black man. That would not have occurred had it not been for the Civil Rights Movement.

And the "Freedom Movement failed" is not only wrong, it fosters hopelessness and apathy because if all that we and those who came before us did — all the organizing, voter-registration, sit-ins, freedom rides, freedom schools, and co-ops — if all that was for naught; and if all that we and those who came before us endured — jailings, beatings, firings, evictions, bombings, lynchings and assassinations — if all that was for naught, than the lesson for today must be:

"I cannot make a difference"

"Nothing ever changes"

"You can't fight city hall".

Back in our day, we young activists of the '50s & '60s were determined to address the overriding issues we faced at that time: the entrenched, explicit, and legally-enforced racial hierarchy of Jim Crow segregation, voting rights broadly denied to nonwhite people, and the ever-present and unrelenting threat of racially-motivated violence and murder.

Back then, a majority of white Americans assumed without doubt or question that, as Chief Justice Roger Taney had ruled a century earlier, "[Nonwhite people are] regarded as beings of an inferior order, and altogether unfit to associate with the white race, either in social or political relations; and so far inferior, that they have no rights which the white man is bound to respect." In the 1950s and '60s, those core assumptions were still deeply embedded in American law and custom, and fiercely enforced by police, courts, and white-violence. The Civil Rights Movement fundamentally changed those assumption — and with it American culture.

Yes, today a significant number of whites still adhere to white-supremacy. Led by Trump and the Republican Party, they battle to "Make America Great Again." But the changes we wrought to law and custom that they so fiercely resent still remain widely accepted in American culture — to their great frustration.

Yes, covert racial segregation and racial discrimination still remain, but in-your-face, legally-enforced segregation is gone forever; and with it "White-Only" restrictions, racially-defined job listings, back-of-the-bus laws, Jim Crow balconies, and separate but utterly unequal public services. So, yes, we do need to continue struggling for racial justice and equality but that does not mean that the movements of the past were failures.

And yes, today voting rights are again under attack as they have not been for decades, but no longer can today's white-supremacists forthrightly declare their that nonwhites have no legal or moral right to elect a president, or for that matter, to vote at all. Rather than broadly denying the franchise to entire demographic populations, they now aim to whittle-down enough Democratic votes, twist and distort enough election rules and policies, and gerrymander enough districts so that the Republican Party — the party of white grievance and white domination — can maintain its grip on political power despite a majority of the population consistently voting against them.

Though not as widely celebrated as ending segregation and winning voting rights, nothing better illustrates the positive changes won by the Civil Rights Movement than the dramatic decline in lynching. Between the end of Reconstruction and the end of the 1960s, acknowledged lynchings — narrowly-defined and excluding deaths under cover of law by police — averaged one per week in America. Think about that, one Oscar Grant, one Breona Taylor, one George Floyd each week. If the definition of "lynching" were expanded as it should be to include other forms of racially-motivated murder such as assassinations, bombings, and vicious racial-animosity (though still excluding law enforcement), the number would greatly increase.

And secret racial murders were probably even more numerous than those officially acknowledged. How many? No one knows. But we do have a clue. When three civil rights workers were kidnapped, tortured, and killed in the summer of 1964, Mississippi's rivers were searched for their remains. The bodies of eight Black men were pulled from those murky waters. Three of them were identified, the other five remain unknown to this day. None of them were the missing three. Eight dead bodies. In one southern state. In one month. Do the math.

Even the acknowledged lynchings were rarely reported in the national news, though a times they were covered as if they were a sports event by a local paper. Even when the killers were known, even when they boasted of their crimes, they were almost never prosecuted. And of those few who did face a judge and jury, almost all were set free. The brutal reality enforced by socially-sanctioned lynching and other forms of white violence was white-rule by reign of terror. Not just against Black Americans, but also Natives, Latinos, Asians, and on occasion other "undesirable elements" such as union organizers, Jews, and "sexual deviants."

Today, racially-motivated murders — and even threats such as nooses — are widely reported headline news. When identified, killers are usually prosecuted and often convicted and sent to prison as were the killers of Ahmaud Arbery in Southeast Georgia last week. Chalk that change up to the Freedom Movement of the 1960s.

Today, our fight is against racially-motivated killing and abuse by law enforcement. Back in the '50s and '60s, murders and bigotry by cops were almost never reported in the news, never officially acknowledged, never statistically tracked. In our day we did try to raise what we referred to as "police brutality." But we made no progress because without video evidence, the white-owned mass media, the white-dominated judicial system, and white America at large, accepted police lies without qualm, question, or hesitation.

Now that we have smartphone and bodycam videos, the struggle for racial justice in law enforcement has become a matter of fierce political debate and widespread public protest — though even with irrefutable visual evidence, prosecution and conviction of killer cops is still the exception rather than the rule.

When I was young, I saw everything in terms of winning and losing. But the Movement taught me that the struggle for social justice is not a win/lose contest. I now understand that human progress is a long, multi-generation journey with no finish line — only milestones.

Yes, our dream was to end racism and injustice for all time. "Freedom Now!" we chanted and sung. But that goal was so far beyond our grasp that we inevitably failed to achieve it. Yet we did reach and pass significant milestones. We forever changed the culture of America in regards to race. We put an end to mass public-acceptance and legal-enforcement of explicit Jim Crow white-supremacy. We established the principle that nonwhite Americans do have an inherent moral and legal right to vote. And we forced law enforcement and mass media to treat racial violence against nonwhites as major crimes rather than distasteful (but necessary) measures to keep them, "in their place."

This is not the first time since the 1960s that we've had to endure and overcome a period of resurgent racism. In 2000, Bush II mobilized the electoral power of white Christian nationalism. He was able to steal the election from Gore because the Democratic Party chose not to risk upsetting white voters by challenging the systematic disenfranchisement of 50,000 African Americans in Florida by the Republican Party led by Bush-bro Jeb. That ushered in an eight year era of right-wing, Chaney-Rumsfeld-Bush rule, wars of choice, rising racism, and economic disaster for We the People.

Shortly thereafter, historian Howard Zinn was invited to give a commencement address, "Against Discouragement," to the graduates of Spelman College, an institution that four decades earlier had fired him because of his support for the Freedom Movement. In it, he reminded us that:

"The lesson of that history is that you must not despair, that if you are right, and you persist, things will change. The government may try to deceive the people, and the newspapers and television may do the same, but the truth has a way of coming out. The truth has a power greater than a hundred lies. ... I learned something about democracy: that it does not come from the government, from on high, it comes from people getting together and struggling for justice."

So no, while the Civil Rights Movement did have its shortcomings, the movement itself did not fail because we successfully carried the torch a significant distance down Freedom Road. And now, as did those who came before us, we hand off to the next generation, and all the generations of freedom fighters to come.

Copyright © Bruce Hartford

[From 1963-1967, Bruce Hartford was a Civil Rights Worker with CORE in California and then in Alabama and Mississippi on the staff of Dr. King's organization the SCLC. Later he was a student activist at San Francisco State College,then a freelance journalist covering the Vietnam War, and then an ILWU chief shop steward in the 1970s. He was a founding member and long-time officer of the National Writers Union in the '80s and '90s. Today he is webmaster of the Civil Rights Movement Archive (crmvet.org), on the board of the SNCC Legacy Project, and a local leader of an Indivisible chapter. He is author of, "The March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom" (2012), "The Selma Voting Rights Struggle & the March to Montgomery" (2014), "Voting Rights in America -- Two Centuries of Struggle" (2018), and "'Troublemaker' Memories of the Freedom Movement" (2019).]

Thanks to the author for sending this to Portside.

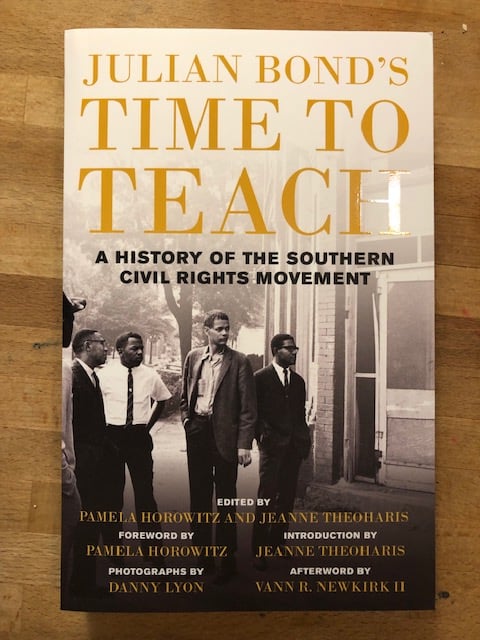

Julian Bond's Time to Teach: A History of the Southern Civil Rights Movement is out in paperback -- and now affordable

A masterclass in the civil rights movement from one of the legendary activists who led it.

Compiled from his original lecture notes, Julian Bond’s Time to Teach brings his invaluable teachings to a new generation of readers and provides a necessary toolkit for today’s activists in the era of Black Lives Matter and #MeToo. Julian Bond sought to dismantle the perception of the civil rights movement as a peaceful and respectable protest that quickly garnered widespread support. Through his lectures, Bond detailed the ground-shaking disruption the movement caused, its immense unpopularity at the time, and the bravery of activists (some very young) who chose to disturb order to pursue justice.

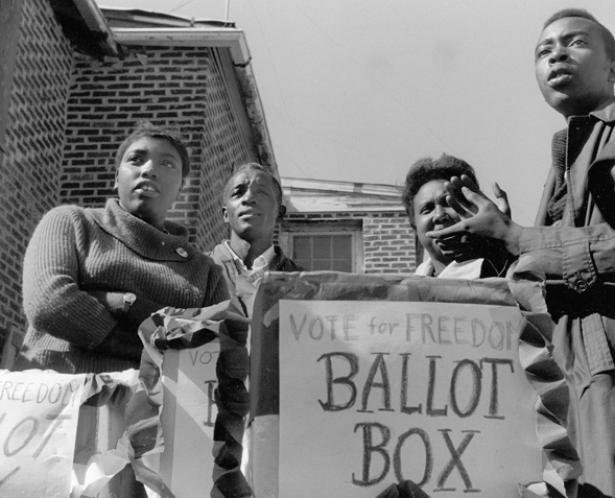

Beginning with the movement’s origins in the early twentieth century, Bond tackles key events such as the Montgomery bus boycott, the Little Rock Nine, Freedom Rides, sit-ins, Mississippi voter registration, the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church Bombing, the March on Washington, the Civil Rights Act, Freedom Summer, and Selma. He explains the youth activism, community ties, and strategizing required to build strenuous and successful movements. With these firsthand accounts of the civil rights movement and original photos from Danny Lyon, Julian Bond’s Time to Teach makes history come alive.

Spread the word