The state was threatening the Roman Catholic Church’s ability to shelter immigrant children when Archbishop Thomas G. Wenski of Miami went for South Florida’s emotional jugular: He compared the unaccompanied children who were crossing the border today to those who fled Communist Cuba six decades ago without their parents.

Offended by the comparison, angry Cuban Americans called Spanish-language radio. They wrote letters to the editor. A discussion at the American Museum of the Cuban Diaspora to denounce the archbishop’s comments turned emotional. Gov. Ron DeSantis, a Republican, who had directed his administration to stop renewing shelter licenses, called the comparison to Cuban exiles who had arrived legally “disgusting.”

Archbishop Wenski and his backers, including a different group of Cuban Americans, pressed on. A news conference to accuse the governor of politicking when children’s lives were at stake. An appearance by an unaccompanied Honduran boy who had been recently reunited with his parents in the United States. And, in the weeks since, an onslaught of radio ads blasting the governor as uncaring.

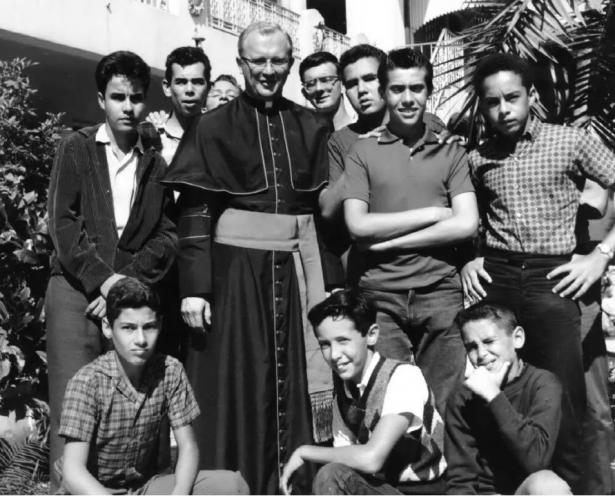

Even in Miami’s knockabout politics, the scrap has been striking, exposing a deep divide among the former children of Operation Pedro Pan, the secret program run by the Catholic Church with help from the State Department that resettled some 14,000 young Cubans after the island’s 1959 revolution. In the past, the program’s beneficiaries, known as Pedro Pans, had largely avoided making internal rifts so public. But for some Pedro Pans today, either Archbishop Wenski’s comparison went too far — or Mr. DeSantis’s policy did.

“We are brothers and sisters, and we don’t fight with each other,” said Carmen Valdivia, who arrived at age 12 in 1962. But, she added, the archbishop and his allies “inserted us” into the debate. “And I resent that.”

Immigration once seemed untouchable as a political issue in Florida, back when Republicans feared that espousing harsh measures would turn away Hispanics, who make up more than a quarter of the state’s population. President Donald J. Trump changed that when he won Florida in 2016 while embracing a hard line on immigration. Mr. DeSantis did much the same two years later.

New state laws followed: In 2019, Mr. DeSantis and the Republican-controlled Legislature banned so-called sanctuary cities and counties, though most analysts agreed that Florida did not have any to begin with. Last year, a federal judge struck down parts of the law, calling it racially motivated. The state has appealed.

Last week, lawmakers sent Mr. DeSantis a bill he has championed that would prohibit state and local agencies from doing business with companies that work as federal contractors transporting immigrants who crossed the border illegally. The state has not identified any such companies, Politico reported.

In this climate, the archbishop’s analogy comparing Cuban children from 60 years ago to mostly Central American children now became especially contentious.

The church’s position is that all children deserve assistance, even if they reached American soil without documents or with the help of paid smugglers. But critics argue that Operation Pedro Pan was different: an organized effort in which children — most of them from upper- and middle-class families — arrived on commercial flights with visa waivers, passports and vaccination records.

Because they were fleeing Communism, Cuban Americans benefited from special immigration policies that allowed them to more easily remain in the United States. They cemented their power by working with both Democrats and Republicans, trying to keep the Cuba issue above the partisan fray. Now, like most everything else, that too has become tainted by polarization.

“The Pedro Pan legacy is so clean — such a good news story — and now it’s stuck in this controversy,” lamented Tomás Regalado, a former Miami mayor and a Pedro Pan.

Lawyers for the office have since told the shelters that they do not need a state license to continue operating. But the state’s proposed new rule requires that a resettlement agreement between the state and federal governments be in place before the shelters can accept additional children.

The governor’s directive prompted Archbishop Wenski — an outspoken figure with a penchant for cigars and motorcycles and a revving engine for a cellphone ringtone — to write an opinion essay in January denouncing the possibility that the church’s Cutler Bay shelter could lose its license. It houses about 50 children now, under Covid-19 protocols, and is one of more than a dozen such shelters in the state, though the only one run by the Catholic Church.

The archbishop, a son of Polish immigrants, is familiar with Miami’s ethnic and racial divisions. For 18 years, he was the parish priest for predominantly Haitian churches, delivering Mass in Creole.

“I was involved with the Haitians when they were showing up by boat at the same time the Cubans were showing up,” he recalled in an interview.

Cubans were considered political refugees, and Haitians economic ones. “But if you interviewed either one, Cuban or Haitian, they would say, ‘I want to work’ or ‘I don’t have a future in my home country,’” he said.

Today’s unaccompanied minors did not get more than a passing mention when Archbishop Wenski and several bishops met with Mr. DeSantis in early February, the archbishop said. The previous evening, Mr. DeSantis, who is Catholic, and his wife, Casey, had attended the archbishop’s Red Mass of the Holy Spirit in Tallahassee.

Archbishop Wenski said he asked the governor at the meeting for a “win-win” that would allow the governor to criticize federal immigration policy — which the archbishop called “chaotic” — while also keeping the shelters open. The governor did not engage, the archbishop said.

Four days later, Mr. DeSantis traveled to the American Museum of the Cuban Diaspora in Miami, where Ms. Valdivia, who is the museum’s executive director, hosted several other Pedro Pans. They shared the governor’s view that comparing them to today’s unaccompanied minors is unfair.

“There’s a lot of bad analogies that get made in modern political discourse, but to equate what’s going on with the southern border with mass trafficking of humans, illegal entry, drugs, all this other stuff — with Operation Pedro Pan — quite frankly is disgusting,” Mr. DeSantis said.

Three days after that, Archbishop Wenski held his news conference with a different group of Pedro Pans, the Honduran family and Mike Fernández, a wealthy health care executive who then financed the radio ads against Mr. DeSantis through a group named American Business Immigration Coalition Action.

“Children are children, and no child should be deemed ‘disgusting,’ especially by a public servant,” Archbishop Wenski said — though the governor had used the word “disgusting” for the comparison with the Pedro Pan program, not the unaccompanied minors themselves.

A spokeswoman for Mr. DeSantis wrote on Twitter that the archbishop “lied.”

Archbishop Wenski acknowledged in the interview that his wording had been “imprecise” but maintained that the only difference between the Pedro Pan children and today’s unaccompanied minors is their countries of origin.

The political right, which likes to defend religious liberty, should allow the church to carry out its mission, he added: “Religious freedom should be freedom to believe and freedom to act on those beliefs.”

Ms. Valdivia said she did not want the shelter to close. But she said she supported Mr. DeSantis’s demand for more information on the migrants.

She said she worried especially about children being abused by smugglers.

Two members of the board of directors for Catholic Charities of the Archdiocese of Miami, which runs the shelter, have departed since the dispute, Ms. Valdivia said. Both were at odds with the archbishop over the issue. The organization’s chief executive declined to comment, calling it an internal matter.

Last year, the archdiocese raised $10,000 for the unaccompanied minors program at a “Havana Nights”-themed fund-raiser of mojitos and dominoes hosted on the Cuban museum’s rooftop.

Ms. Valdivia said Archbishop Wenski was still welcome to hold the event there again this year, as is planned. She has already reserved the date.

Kirsten Noyes contributed research.

[Patricia Mazzei is the Miami bureau chief, covering Florida and Puerto Rico. Before joining The Times, she was the political writer for The Miami Herald. She was born and raised in Venezuela, and is bilingual in Spanish. @PatriciaMazzei • Facebook]

Spread the word