books ‘Ballad of an American’: The Illustrious Life of Paul Robeson, Newly Illustrated

One of my favorite Paul Robeson songs is “Jacob’s Ladder.” It originated as a slave spiritual, based upon the Biblical story of a dream that Jacob, the patriarch and leader of the Israelites, once had. A ladder went from Earth to heaven, with angels traversing up and down it. For enslaved people, it signified the hope that they could climb out of slavery and into freedom. When Robeson sings, the listener can feel this climbing, heading toward freedom, giving the song not just a spiritual meaning but one hoping for the end of all oppression, not least that of the working masses to which Robeson devoted much of his life. The verses and the melody are simple, but their power is undeniable. It is a song of hope, and it encourages, even demands, a dedication to realize that hope.

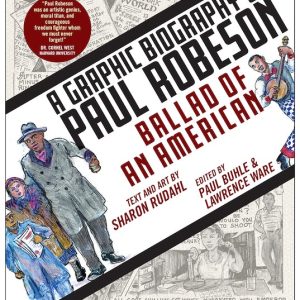

Ballad of an American: A Graphic Biography of Paul Robeson

By (artist) Sharon Rudahl

by Sharon Rudahl

Edited by Paul Buhle and Lawrence Ware

Rutgers University Press; 142 pages

Paperback: $26,96

October 16, 2020

ISBN: 9781978802070

Download/Print Leaflet (from Rutgers University Press)

The book, Ballad of An American, is a beautifully rendered graphic biography that takes readers, especially those not familiar with Robeson, on an exciting journey through his remarkable life. He rose like a shooting star, from humble beginnings to the height of worldwide acclaim—and he fell nearly as rapidly as he shot to stardom, destroyed by the U.S. government and powerful right-wing elements after the Second World War. He was deemed a danger to the white and imperialist ruling class, and with good reason. As we shall see, what Robeson stood for and acted upon threatened to incite an uprising by the working class, especially the Black superexploited part of it.

Robeson was born in 1898, the youngest of five children, in Princeton, New Jersey. His father, William, born enslaved, was a Presbyterian minister, and his mother, Maria, was a schoolteacher. Maria, who was nearly blind, died tragically in a house fire when Robeson was 6 years old. His father lost his job at an all-Black church in Princeton, probably for race-related reasons, forcing the family to move. They took up residence in Somerville, New Jersey, a town much more working-class than Princeton and with a larger Black population. William obtained employment, again as a minister, and this time more secure than in Princeton. Even before he was a teenager, Robeson showed great promise as a student, and his voice drew attention, so much so that he sometimes gave sermons in his father’s church. He excelled in all of his academic subjects.

His elementary school was all Black, but Somerville High was not, and Robeson felt the slings and arrows of racism. Still, his overall excellence in everything could not be ignored, and his music teacher made him soloist of the Glee Club. He starred as Othello in a school play, a role he would famously reprise many times as an adult, in venues around the world. He was also a gifted athlete, lettering in baseball, basketball, track and field, and most notably in football where his size, skill, grace, and power overshadowed that of everyone else.

Despite the high school not informing him of the statewide, two-part (the first taken as a high school junior and the second as a senior) examination that Rutgers University had initiated, with the winner receiving a full scholarship, Robeson took both parts on one day in his senior year. He got the highest score in New Jersey and thus entered the university, with its campus in New Brunswick, in 1915. It was then an all-male, private college with about five hundred students. There he once again excelled in everything he did: in his studies, in acting, in singing, and in sports, where he earned fifteen varsity letters, in track and field, baseball, basketball, and football. Rutgers excelled in football during Robeson’s tenure there, and he was selected an All-American in 1917 and 1918. He was one of four Rutgers students to be inducted into Phi Beta Kappa, and he was valedictorian of his class.

After graduation, Robeson attended and graduated from, with some delays to earn a living, Columbia Law School. He played professional football for three years in the American Professional League, forerunner to the National Football League. He lived in Harlem just as the Harlem Renaissance was beginning. With his athletic fame, his outgoing personality, and his good looks, he was a popular sight on Harlem’s streets and at parties.

He had a passing acquaintance with a young woman from a prominent family, Eslanda Goode, a college graduate with a degree in chemistry. Goode was working as a lab technician when Robeson suffered a football injury and spent a few days in the hospital where she was employed. She spent time with him, making sure he was well taken care of, even making notes for the law school classes he missed. They began to see each other, and a year later, in August 1921, they were married. He was 23 years old, and she was 25. They stayed together, through many ups and downs until Goode’s death in 1965. To say that their relationship was tumultuous might be an understatement.

Goode continued her work as a chemist for several years after her marriage to Robeson, but she was keenly interested in promoting his burgeoning talents, as a singer and then as an actor. She soon began to devote all her time to his career. The book’s illustrations and text show what happened. He took roles in theater productions in New York City and was invited to perform in one of these. Robeson went to London, where he not only acted but also met the singer, pianist, and composer Lawrence Benjamin Brown, who became his accompanist and close friend over the following forty years. Through Brown, Robeson began to sing the spirituals so important to the Black experience in the United States from slavery onward.

After London, Robeson returned to the United States, where Goode had undergone surgery but kept it from him so that he could begin to lay the foundations for his subsequent career, then to the rest of Europe, acting and singing. His politics deepened, and he moved steadily to the left. He took the world by storm, stunning audiences with his fine acting and heart-stopping singing. He became a global force for the liberation of Black people in the United States and workers around the world. He studied African history and languages. He sang in multiple foreign tongues, everywhere captivating those who met him or watched him sing and act. He was, in a word, a phenomenon. He visited the Soviet Union and became a lifelong ally of the world’s first socialist society. He wanted nothing less than the liberation of all those exploited, alienated, and robbed of their humanity by capitalism. To see him among Welsh coal miners, with whom he had a special affinity, is to witness something very special. The white miners, blackened by coal dust, showing deep love and affection for a Black man from the United States, fill us with both wonder and feelings of the solidarity that should be at the foundations of human existence.

As the editors of this book, Paul Buhle and Lawrence Ware, tell us in their afterword, Robeson arose to great prominence during the time of the Popular Front. This was a period stretching roughly from the election of Franklin Delano Roosevelt as U.S. president in 1932 until the candidacy of the progressive politician and former Vice President Henry Wallace in 1948. Many radicals, including those in the Communist Party of the United States, made alliances with liberal Democrats in support of the New Deal, the mass union organization of industrial workers, and a united front against fascism in the Second World War, including support for the Soviet Union after the Nazi invasion of that country in 1941. The proponents of the Front believed that it would greatly increase the popularity of socialism, and its achievements would pave the way toward a radical transformation of society. A person like Robeson, who had great “crossover appeal,” was an icon of the Popular Front, with fans both white and Black and from every corner of the Earth. He was a symbol of multiracial and multiethnic solidarity.

However, under the surface of potential working-class harmony was a darker reality. While it appeared that right-wing and fascist forces had been vanquished by the Popular Front and the victory against fascism in the War, they remained alive and active. Already during the war, the dominant economic and imperial powers, Great Britain and the United States (the latter now headed by the reactionary and racist Harry Truman), were plotting against their ally, the Soviet Union. No sooner had the war ended than a new, Cold War, began. The Soviet Union was now public enemy number one, and the nefarious machinations against it by the dominant capitalist nations hardly need to be recapitulated. The allies, minus the USSR, quelled Communist political advances in France, Greece, and Italy.

The newly formed Central Intelligence Agency began to undermine radical movements all over the world. Domestically, a Republican Congress enacted, in 1947, the antilabor Taft-Hartley amendments to the National Labor Relations Act. This law contained a provision demanding that union officers sign an oath stating that they were not communists. The two dominant labor federations, the American Federation of Labor (AFL) and the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO), capitulated to this statute, and not long after, the CIO expelled ten unions, among which were the most militant, with the best collective bargaining agreements, and with the greatest commitment to racial and gender equality, as well as the most principled opposition to growing U.S. imperialism. The CIO also abandoned its Southern union organizing campaign. Radical labor leaders were also expelled or marginalized in individual unions, including the United Auto Workers. They were also hounded by the FBI and federal and state Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC).

After the Second World War, there were massive strikes in the United States, and a burgeoning civil rights movement was coming to life. Despite the forces of reaction, there were possibilities for a labor-civil rights alliance. Robeson would certainly have been an important catalyst for such an alliance. He had a superlative speaking ability; his knowledge and connections were enormous; and he was still popular. What is more, he was a fervent anticolonialist, right when tens of millions of people living in the colonies of the rich imperial powers were demanding freedom. No doubt, he could have helped galvanize support among U.S. workers and the civil rights movement for the anticolonial movement.

The U.S. government was quick to neutralize Robeson. He met with Truman in July 1946, urging the president to support anti-lynching legislation. The racist bomber of Hiroshima and Nagasaki gave him short shrift. Robeson’s friends in the Communist Party were being prosecuted—persecuted—for their thoughts, as anticommunist hysteria hit full stride. Robeson supported Wallace’s presidential run, and after that politician’s landslide defeat, he and those who supported him were suspect, much like those who fought on the side of the loyalists in Spain a decade before were now declared to be “premature antifascists.” When Robeson spoke and sang at progressive venues in Europe, U.S. newspapers denounced him as anti-American. His friendship with the Soviet Union was now seen as a betrayal of his country. Racist mobs began to harass him, most notably at a concert in Peekskill, New York, where racists and antisemites attacked his followers in August 1949. Even Jackie Robinson, who should have known better, denounced Robeson before HUAC. Theaters refused to book him during a U.S. tour. Then, when he prepared to travel to Europe to perform, he discovered that his passport had been revoked. The U.S. government declared that “Robeson’s travel abroad would be contrary to the interests of the United States.” He was even denied the right to travel to Canada, which did not then require a passport. So, in 1952, he gave the first of his famous open-air concerts in Blaine, Washington, at the Peace Arch on the border between the two countries.

Goode was compelled to testify before HUAC in 1953, soon after becoming ill with breast cancer. She had a mastectomy and recovered rapidly. Robeson also became sick, and for him, this was the beginning of two decades of mental and physical decline. He underwent various treatments, including heavy doses of drugs and multiple electric shocks, as well as psychotherapy (the authors of the book argue that recent studies of the brains of deceased modern football players suggest that Robeson may have suffered from Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy, the result of concussions suffered while playing football). Still, he continued to perform, even using telecommunications to reach audiences abroad. He kept speaking out against injustices, including at a compelled appearance before HUAC. His passport was restored by the Supreme Court in 1958, and he was able to travel overseas. He sang once again in support of the cause of liberation. However, his health was not good. He could not remember the lines of Othello, a part he had acted so many times. At home, his films and recordings disappeared from the marketplace, and though the McCarthy period ended, anticommunism remained in full force. Robeson was further castigated for his friendship with the Soviet Union, for his failure to condemn the persecutions and executions enacted under Joseph Stalin. Ultimately, he faded from public view, and he was even marginalized by the more militant wings of the Black freedom struggle. His film and stage roles were dismissed as stereotypically subservient Black men.

Goode’s cancer returned, and she died in 1965. Robeson was too distraught to attend her funeral. He hung on for ten more years, cared for in Philadelphia by his sister Marian. Already toward the end of his life, he received honors, including in 1967 the opening of the Paul Robeson Cultural Center on the Rutgers campus. After his death, many other honors were bestowed upon him; the U.S. Postal Service even issued a Robeson stamp.

This review began with a Robeson song, so it is fitting to end with one. In 1945, a short film, The House I Live In, was made to counter post-Second World War antisemitism in the United States. Written by Communist Party member Albert Maltz, sent to prison in 1950 as one of the “Hollywood Ten,” persecuted for their refusal to testify before HUAC in 1947, the movie featured Frank Sinatra singing the title song. The song was written by Abe Meeropol, who used the assumed name Lewis Allan. He was the adoptive father of the children of the executed radicals, Ethel and Julius Rosenberg, as well as the writer of “Strange Fruit,” the gut-wrenching song about the lynching of Black people. To people of a certain age, the lyrics of “The House I Live In”—especially when sung by Robeson, the man who made it famous—strike an emotional chord. They reflect more hopeful times: the period of the Popular Front.

The afterword, perhaps unwittingly, gives the impression that, since Robeson was a product of the Front, a modern version of the Popular Front is needed now. Perhaps such a development would provide the political conditions in which Robeson could regain the prominence he once had. Because despite all the accolades he has received, he is not well-known among those who have turned to the left in the past few decades. However, it is unlikely that a new Popular Front will arise. What we need now is an openly radical movement, one aimed at substantive equality in all spheres of life, a planned degrowth in terms of production, a frontal assault on structural racism and patriarchy, and a refusal to participate in any way in the imperial machinations of the United States. Alliances of those dismissed today as on the far left with liberals and social democrats will be of limited values, given that these political entities are the very ones dismissing those of us who have stayed the course and demanded the complete annihilation of capitalism.

Such a radical movement, of the world’s workers and peasants, is what Robeson embraced. It is in such a movement that he will once again stand out as perhaps the greatest radical artist in history. For it is not just his astonishing, multidimensional talent that made him great and worthy of our admiration, but his unyielding commitment to a world in which freedom thrives because necessity has been conquered. If this book helps readers see this, that despite his all-too-human flaws, his life is a light toward which we should all travel, then it will have more than done its job.

Spread the word