On October 7, 2024, Or Gabbay felt miserable thinking of "the catastrophe." The soft-spoken 30-year-old waiting for a train in the central Israeli city of Lod has a shy smile and a chubby baby named Yaeli, just under a year old, with tiny studs in her pierced ears.

Gabbay says he has lost all trust in the state, along with any sense of security. He thinks the Gaza war hasn't gone far enough.

"There's no other choice," he says, ominously. "My views are sort of harsh. I won't say to kill them, but in the U.S., if someone did that, they can take away their citizenship. I think that's completely fine, anyone should agree to that."

It hardly matters that Palestinians under Israeli occupation are not citizens – he was talking generally. Gabbay, a law student, laments that Israel has no strong leader like Russian President Vladimir Putin. When pressed if there is any Israeli leader who represents his views, he answers awkwardly: "If I were to say [National Security Minister Itamar] Ben-Gvir, they still wouldn't give him the means to do it."

Every long-term poll trend from my 25 years of survey research, political analysis and cyclical wars indicated that October 7 would cause Israelis – at least Jews – to flood further to the right.

A whole new right

One year after the Hamas attack, Israel's government seemed to prove the point – careening to the far right. The parties and people currently in power seem to have completed a decades-long transformation into something unrecognizable to earlier generations of the Israeli right.

The old, classic right in Israel fused a commitment to the "rational state" – poli-sci talk for a state based on civic institutions with the citizen at the center – and hawkish national security positions, alongside free market economics, says Yossi Shain in an interview.

Shain is professor emeritus of political science at Georgetown University and Tel Aviv University, and served briefly as a lawmaker for Yisrael Beiteinu, the party of Avigdor Lieberman. As for religion, he refers to Ze'ev Jabotinsky's argument that in a future state, Jewish religion mattered only for collective identity; state institutions must be secular, and halakha (Jewish law) represented something like a "mummified corpse" – Jabotinsky's words.

Likud has long since jettisoned the last generations of the classic Israeli right. No young guard of liberal-oriented politicians is joining Likud today. And even many religious Jews in Israel recall the earlier generations of the National Religious Party with some nostalgia, viewing them as more moderate than the current brand of fundamentalist, messianic populists in its latter-day successors, Religious Zionism and Otzma Yehudit.

The meaning of the "right-wing" ideological label has also shifted to a new set of policies. For a long time, beginning roughly in the early 1990s, the difference between right and left in Israel referred mostly to attitudes toward land concessions for peace, a two-state solution, settlements, West Bank annexation.

But since October 7, right-wing conversations focus on using more force in Gaza; the conquest and resettlement of Gaza; major strikes on Hezbollah or Iran; and, of course, levels of support for the leaders who advocate these things.

Finally, over the past 12 months, the current government translated these ideologies into reality. Seizing on October 7 to rail against the Oslo Accords and the 2005 dismantling of Gaza settlements, the government burned rubber to undo both.

By blocking West Bank workers from coming to Israel, and withholding taxes Israel collects for the Palestinian Authority, Finance Minister Bezalel Smotrich brought it to the brink of budgetary and institutional collapse. The Israeli army launched a major operation in the heart of Palestinian cities and refugee camps in Area A. Each such move is one step closer toward the government's original, stated aim: full West Bank annexation.

Governing coalition figures began to advocate rebuilding Gaza settlements almost immediately after October 7. Lawmakers and ministers from the coalition participated in an ecstatic conference in January calling to resettle Gaza and transfer the Palestinians. A second conference in August by a Gush Katif heritage group was suffused with missionary fervor and well attended by public officials.

Likud, the party that has been the standard-bearer of the Israeli right since its founding, has become ideologically indistinguishable from what Israelis call the hard right for one reason: Benjamin Netanyahu.

Too often, observers excuse his policies by insisting that he's not ideologically far right but trapped by his fundamentalist allies, since his corruption trials make him haram/mukseh for others.

He can't accept a hostage deal and a cease-fire, in this view, because these coalition partners have threatened to collapse the government. But this logic is dubious.

Smotrich and Ben-Gvir's polls aren't good enough to secure their political future if they topple the government. Netanyahu could have called their bluff; Smotrich already changed his mind to support the first (and only) hostage deal in November.

Netanyahu has happily followed their lead on other issues. In January, Smotrich began insisting that the Israel Defense Forces take over distribution of humanitarian aid in Gaza – which he saw as the springboard to a military government (de facto, direct military rule). Recently, Netanyahu has openly embraced the idea – and plans are moving ahead.

On Iran, when Netanyahu stood before the U.S. Congress in 1996, 2011, 2015 and 2024 to excoriate Iran as the greatest threat to the world, he wasn't "just clinging to power." Or perhaps he was – since he has long believed that a shadowy left-wing, deep-state elite seeks to bring him down, and anything goes to save his political position – which means saving the state from existential destruction. Ideology and politics have become inseparable.

Netanyahu swore that there would never be a Palestinian state on his watch in 2015 – a year before his corruption investigations began – and made this policy a reality. He appointed Ayelet Shaked as justice minister that year, when her anti-Supreme Court positions were well-known. His own Likud cosponsored illiberal legislation and attempts to constrain the court even in his comeback term (2009-2013). As Israelis say these days, "You're the leader, you're responsible."

A Likud MK he backed over the years, Yuli Edelstein, spoke at the Gush Katif conference in August; a Likud minister, Shlomo Karhi, attended the one in January. If it sounds insane to imagine Israel conquering southern Lebanon and building settlements there, that's how these things start – with the fringe right becoming ever-more mainstream.

And yet…

October 7 should have handed this unbound, wild-eyed right wing the perfect storm for success: wartime rallying and vengeful fury. But something in the picture is off; the public isn't entirely there.

The parties of the original coalition collapsed in the polls for the first six months of the war. They crept up for the next six months, but haven't been able to get to a majority of Knesset seats since January 2023.

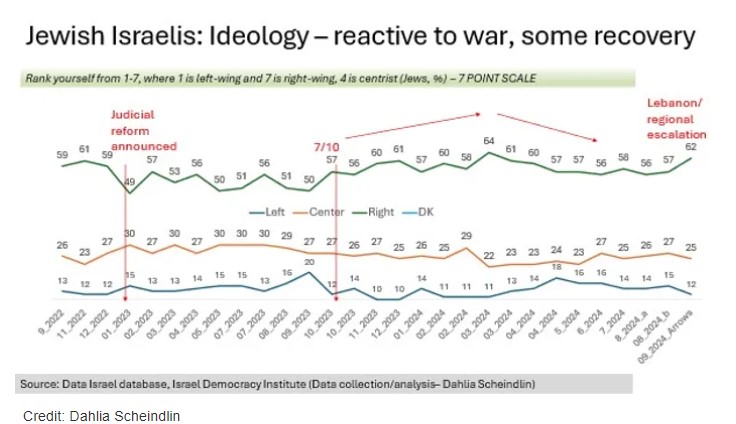

Around the November 2022 elections, polls from the Israel Democracy Institute showed that about 60 percent of Jews self-identified as right wing. Interestingly, that portion had declined steadily in the institute's polls during the democracy protests of 2023, down to 50 percent in September. October 7 and the war prompted a rise again, to 64 percent within a few months. But "right wing" drifted back down to 56-57 percent in recent months.

The portion of Jews who self-defined as left eroded at first, but stabilized at 12 percent – close to the levels before the 2022 elections (during 2023, that number rose). Israel's massive escalation against Hezbollah pushed the right slightly above 60 percent in the institute's September poll, but these trends are clearly not quite fixed.

Behind the numbers, the city of Lod offers what some have called a microcosm of Israel's pressure cooker. It is home to former Soviet immigrants, Mizrahi Jews, Ethiopian Israelis – many of them religious – Palestinian citizens and Garin Torani, a religious-Zionist movement that sets up communities in underdeveloped areas. In May 2021, Arab and Jewish citizens clashed violently there, in the shadow of a 10-day Gaza flare-up.

In 2022, 28.53 percent of Lod's voters chose Likud, and 15.5 percent for the combined slate of the far-right Religious Zionism (Smotrich) and Otzma Yehudit (Ben-Gvir) – in total, 10 points higher than the national average for those two parties.

Orit Ofer, 46, directs the culture department at the Lod municipality. She grew up in the West Bank settlement of Kiryat Arba, in a religious family with eight siblings, and has four of her own children. She's lived in Lod for 16 years. Before that, she was an activist opposing the 2005 evacuation of Gaza settlements and served as secretary of the West Bank outpost of Amona, evacuated in early 2006. She was a parliamentary assistant for a Likud lawmaker, and says she's still a proud member of Likud because she believes in the need for a big right-wing party.

But in an interview at her office in the Lod municipality, she offers veiled frustration with Netanyahu, indicating that Likud clings to its leaders for too long. She herself is no longer religious and has become disenchanted by the inner workings of politics, including within Likud.

Given that her daily job involves very close ongoing relationships with the local Arab community, not least after the urban intercommunal violence of 2021, did the latest war cause a new wave of fear or tension? "The opposite."

She explains that the municipality was unprepared for the 2021 riots and worked hard to build coping skills for the future. When this war broke out, the staff quickly set up "situation rooms," including in the Arab community, and she believes this helped maintain calm. They mourned and even cried together.

How has the state performed during the war? "I'd rather not say. We're lucky that we have local government."

Her views toward Palestinians are hard-line, but distinct: "They have to decide if they want to be part of the state and accept our sovereignty. If they do – they should have equal rights. Including the right to vote. If they want to fight – we'll have to fight."

Ofer says she could never support Ben-Gvir or Smotrich or their parties, which she sees as driven by narrow sectarian interests: "They want to control things always at the expense of others." The war didn't really change her overall views, she says, just made them stronger.

Gabbay, the young father in the Lod train station with his self-defined "harsh" views, also says October 7 didn't truly change his worldview regarding the conflict. "What happened was my nightmare." He could well be among the stable base of support Ben-Gvir retains in surveys.

Two Ethiopian-Israeli women on a bench chatting in Amharic chuckle sadly when asked how they felt on October 7, 2024. They had just been having that same conversation among themselves, they say. All they could relate was how hard this day was, how sad they are – and "how, how could this have happened to us?"

Someone will have to answer for it. Those no longer supporting the government – or the centrist Yair Lapid – are favoring the hawkish secular right, including Lieberman, Benny Gantz and Naftali Bennett. Trying to explain Lieberman's rise, Shain says: "They are looking for a leader who is strong, secular, not clerical, liberal … but very tough on security."

Israel is headed nowhere good. But secular right-wing hawks driven by a modern, pragmatic view of the state might lead the country in the future. If they are truly pragmatic, they'll start thinking now about how to undo everything Netanyahu and the fanatical right wing have done.

[Dr. Dahlia Scheindlin is a leading international public opinion analyst and strategic consultant specializing in progressive causes, political and social campaigns. She is the author of The Crooked Timber of Democracy in Israel: Promise Unfulfilled.]

Spread the word