During an April 16 event at the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, Joe Kefauver—a lobbyist and PR man for the National Restaurant Association and the Convenience Store Association—warned the audience of business leaders about an emerging challenge to their corporate dominance. The threat comes, he said, from groups that “have the ability to leverage infrastructure to bring a multi-pronged attack, and force internal corporate changes they wouldn’t have been able to get through collective bargaining.” Though the organizing efforts the Chamber warns about take many forms, corporate PR lumps them together under the label “worker centers.”

At the same Chamber event, Kefauver gloated about industry’s recent successes in weakening “the union movement,” which, he said, “has hit a lot of roadblocks, in large part due to the good work of a lot of folks in this room.”1 Building on their victories, over unions, corporations are now deploying their firepower against a resurgence in low-wage worker organizing prompted by the worst economic inequality in a century.

The stakes are high. For too many working Americans, chronic debt and economic insecurity have become inescapable facts of life. Institutions that once offered refuge and the hope of escape from poverty have been hollowed out by decades of policies that concentrate wealth in fewer and fewer hands. Labor unions have been decimated by business interests’ relentless anti-unionization campaigns, and by their successful lobbying in Congress and state legislatures for laws and regulations that favor employers.

As workers face intimidation and legal challenges to their right to join unions (including a case that would damage public sector unions, Harris v. Quinn, on which the Supreme Court is about to rule2), the United States has gained a reputation for lousy treatment of workers. In a new report, the International Trade Union Confederation used a five-point scale to rank countries on their commitment to workers’ rights, with five being the worst. The United States received a ranking of four, meaning there are systematic violations.3 Only about 11 percent of U.S. workers are now represented by unions, down from a peak in the private sector of around 35 percent in the 1950s.4 Today, most union members are public-sector employees such as police officers, teachers, and government workers.

Without unions to advocate for workers’ rights at the local level, employers are able to keep wages low and suppress worker self-organization with impunity. Workers’ rights advocates have documented abuses—such as wage theft, intimidation, and sexual harassment—being committed against immigrant and low-wage workers without fear of prosecution. Inequality is at its highest level since 19285, and studies show that 95 percent of the financial gains made during the current recovery have gone to the top one percent of income earners.6

Into this breach has stepped small but vibrant constellation of low-wage and immigrant-worker organizations. This organizing resurgence features a variety of structures and approaches striving to ensure that workers’ voices are heard in public-policy debates on wages and employment practices. According to a recent briefing paper by United Workers Congress, a federation of such groups, “Worker centers [and other low-wage and immigrant worker advocates] have won changes in local policies and practices, built vocal and active membership, and raised public awareness of workers’ issues. These efforts have laid the groundwork for the recent spread of legislative efforts to protect the rights of workers not covered under existing labor law, and to raise the minimum wage for all workers.”7

Such organizing efforts have also drawn the attention of corporate wolves—PR flacks and conservative-leaning think tanks answering to the same business interests that are responsible for the decline of unions and other anti-poverty institutions. While some new worker organizations have endured and even thrived in the face of relentless attacks, their antagonists have generally hailed from the particular industry (restaurant, agribusiness, big box retail, etc.) or social sector (e.g. anti-immigrant movement) that they challenge.

In the court of public opinion, low-wage and immigrant worker organizing campaigns are gaining a reputation for being scrappy underdogs, standing up for the little guys. (More often than not, these “little guys” are actually women; a recent study from the National Women’s Law Center found that women represent almost two-thirds of minimum wage workers.8) But the business lobby is trying to use its megaphone to reverse that momentum. Groups like the U.S. Chamber of Commerce and the National Restaurant Association are taking advantage of low public awareness of new worker organizations to frame these loosely connected groups as part of the union “Goliath”—a familiar frame that allows corporations to repurpose decades of anti-union messages and tactics.9

Although the attacks are well-coordinated, there are opportunities for low-wage and immigrant worker organizing to respond strategically. The business community is trying to hit a field of small, moving targets with independent leadership. The strength of the field lies partly in its diversity—its networked strength rather than its deep pockets. The opposition is trying to homogenize a heterogeneous field of grassroots organizing in order to simplify, vilify, and attack it. The experienced operatives at the U.S. Chamber of Commerce refer to their chosen targets as “worker centers,” using the term to merge all organizing efforts—union and non-union, immigrant rights’ groups, domestic workers, food service and retail workers, day laborers, supply chain workers, and more— together into one single, seemingly formidable enemy.10

Wage Thieves

Attacks on worker organizing are taking place against a backdrop of an economy in crisis. A 2013 New York Times article, quoting a report by the Center for Budget and Policy Priorities, noted that the “median income for working-age households (headed by someone under age 65) slid 12.4 percent from 2000 to 2011, to $55,640. During that time the American economy grew more than 18 percent.”11

As real wages stagnate or fall, consumers have less money to spend. In response, big corporations seek to preserve their profits in ways that further squeeze workers and their disposable income. This squeezing takes many forms: scheduling workers for fewer hours on the shop floor, spreading fear and anti-union propaganda, cutting back on benefits packages, and, perhaps most shockingly, committing outright wage theft.

Imagine being hired as a cashier at a big-box retailer and being told that you’ll make $8.81 per hour, the average wage of a Walmart cashier.12 Imagine getting your meager paycheck and finding that it’s even less than you expected. Now imagine learning that the missing money isn’t being withheld by mistake. It’s being stolen by your employer. Such wage theft is pervasive across all U.S. industries, and the sums involved amount to much more than petty larceny.

“When we measure it,” Gordon Lafer, a political economist at the University of Oregon’s Labor Education & Research Center, recently told Moyers & Company, “the total amount of money stolen out of American workers’ paychecks every year is far bigger than the total amount stolen in all the bank robberies, gas station robberies, and convenience store robberies combined.”13

“It really has become for many industries the way they do business,” said Sally Dworak-Fisher, lead attorney in the Workplace Justice division at the Public Justice Center in Baltimore, Maryland. “By not paying overtime or paying less than the minimum wage, they are eroding the bedrock of labor protections in this country.”14

The phenomenon of wage theft is especially cynical given the amount of money that low-wage employees already produce for their employers: McDonald’s, for instance, makes an average per-employee revenue of $65,000, according to a report from the business blog “24/7 WallStreet,” derisively titled “The Companies with the Least Valuable Employees.”15

In an article for Alternet in 2013, Paul Buchheit wrote that “McDonald’s employs 440,000 workers worldwide, most of them food servers making the median hourly wage of $9.10 an hour or less, for a maximum of about $18,200 per year.”16 That $9.10 per hour McDonald’s employee is being paid less than one-third of what she earns for her employer in a year. Now she is also having those meager wages stolen, as the Labor Department found in at least two recent cases in New York and Pennsylvania.17

Wage theft is just one of a variety of weapons that private-sector businesses have deployed in order to cheat workers and maximize profits. Other tools include public policy instruments like so-called right to work laws that hamper union organizing; threats of deportation to keep unauthorized immigrant workers from asserting their rights; and lobbying to carve out loopholes in new worker-protection laws, among other devices.

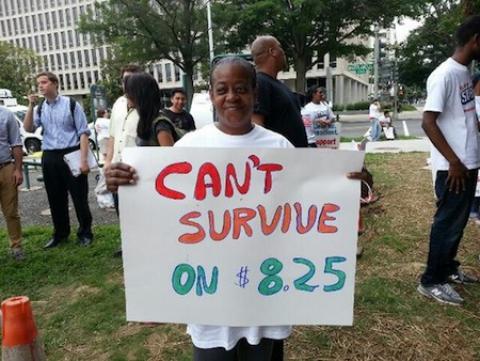

For the past few years, in metro regions and states, workers and their communities have galvanized around the problem of wage theft, standing together to sue and win back money that rightfully belongs to the workers who earned it and the local communities where they spend their paychecks. Additionally, low-wage and immigrant workers are seeking relief from abusive and exploitative working conditions by expanding the laws that defend their interests—raising the minimum wage, creating stiffer penalties for wage theft, and instituting paid sick days and other basic workplace protections. Their grassroots organizing—sometimes, but not always, conducted in partnership with unions—has been effective, and a growing number of cities and states are passing these new laws.

Corporate interests are striking back with bills to pre-empt cities from passing their own minimum wage increases or to mandate paid sick days. These pre-emption bills are produced by right-wing bill mills like the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC) and pushed by state lawmakers who are often groomed for office by corporate lobby groups such as the U.S. Chamber of Commerce.18

The legislative attack is well underway. Eleven states, including Wisconsin, Florida, and Oklahoma have already passed state-level “pre-emption” laws banning cities and counties from mandating employer-provided paid sick days. At least six other states, according to the watchdog group Center for Media and Democracy, are currently considering similar pre-emption bills that would prohibit local governments from raising the minimum wage.19

Chamber of Horrors

When the Los Angeles-based Koreatown Immigrant Workers’ Alliance (KIWA) began urging city voters in 2012 to support a state bill that would allow workers to place a temporary lien on the business owner’s property if the business owner committed wage theft, KIWA’s members were excited. The bill would have allowed workers whose employers had stiffed them to place a lien—that is, a transfer of possession— on the employer’s property until workers received the back pay they were owed. A lien is a red flag for lenders and can become a PR problem for employers. “We see this lien as a tool to bring employers who are committing wage theft to the table,” said Alexandra Suh, KIWA’s executive director. “If there’s a lien on the table, they’re going to pay attention.”20 One state—Maryland—passed a similar lien law that went into effect in October 2013.

Dworak-Fisher of the Public Justice Center said she expects that Maryland’s law will deter employers from committing wage theft. “We’re just getting it up and running,” she said. “We’ll be bringing wage lien claims over the summer and into the fall. The unscrupulous employers will be on notice.”21

As the California campaign gained steam, however, local politicians and business owners—some of whom were involved with KIWA projects in the community—started getting notifications from the California Chamber of Commerce. These Facebook ads, blog posts, and other advertising materials claimed that the anti-wage theft bill posed a danger to homeowners.

In one ad shared with PRA, the California Chamber falsely claimed that if the bill passed, it would mean that a third-party homeowner who had a contractor or cleaning service work in the home could wind up with a lien on the home. “Despite the fact that the third party homeowner had absolutely no control over the employee’s work or the wages he/she was paid,” read the statement from the California Chamber, “that homeowner could have his/her property leveraged for unpaid wages of the company’s employees.”22

In reality, the bill explicitly prevents third-party liens, or liens from one company’s workers on a third party’s, or homeowner’s, property. Yet the Cal Chamber’s lie confused and frightened California homeowners. The anti-wage theft measure died in the state Senate in January 2014. When it was brought up again for a vote in the State Assembly on May 28 of this year, it passed by a vote of 43-27. It now moves back to the California Senate for a potential vote later this year.

The corporate smokescreen also obscures the widespread nature of the problem, which continues to be “very, very serious,” as Suh said.23 Indeed, a 2010 UCLA-sponsored survey showed that the vast majority of workers are experiencing some type of wage-related violation on the job in Los Angeles County. “Low-wage workers in L.A. County frequently are paid below the minimum wage, not paid for overtime, work off the clock without pay, and have their meal breaks denied, interrupted, or shortened,” according to the report. “In fact, 88.5 percent of workers in the L.A. sample had experienced at least one type of pay-related workplace violation in the week of work before the survey.”24

Lies, Smears, and Innuendo

The high-profile battle in California may have helped provoke an aggressive response from the national business lobby: the U.S. Chamber of Commerce. The Chamber’s Workforce Freedom Initiative (WFI) has released three faux-academic reports on low-wage worker organizing since last fall, starting with one in November 2013 that purported to expose a cabal of left-wing, foundation-funded, low-wage worker advocacy groups like KIWA.

The report presents a kind of historical analysis of how low-wage and immigrant worker organizations emerged; labels this highly diverse landscape of organizations “worker centers”; charges that they are “union front groups” (UFOs) that circumvent the many restrictions that tie the hands of unions; and maps foundation funding for the low-wage organizing sector (implying that foundations are as responsible as unions for its existence). The report fingers worker-advocacy groups of varying forms and sizes—from small worker centers such as KIWA to larger national organizing efforts like Restaurant Opportunities Centers United (ROC United) and Organization United for Respect at Walmart (OUR Walmart).25

Each subsequent U.S. Chamber report builds on the insinuations and distortions of the previous ones. Common to all of them is an effort to redeploy the rhetoric and regulatory efforts developed over decades against unions to attack these varied immigrant and low-wage worker projects that, while generally small, have become among the most dynamic sites of the worker-organizing resurgence. The Chamber’s approach requires convincing the public, policy makers, and judges that so-called “worker centers” are more or less all the same—that they are functionally unions, trying to represent workers for the purposes of collective bargaining while evading the regulatory scrutiny and restrictions on their behavior and funding that unions must endure.

In reality, worker organizing groups use a variety of tactics to achieve their strategic goals: a community organization files a lawsuit to stop local police from using traffic stops to hand immigrant workers over to immigration authorities; a worker center holds workshops to train members to prevent wage theft; or a local domestic workers’ organization holds a rally to call for an end to deportations. In none of these cases is a worker organization “seek to negotiate with employers on behalf of employees,” as the WFI report asserts.26

It is unsurprising that the corporate Right should want to fight on familiar ground. The loud “union front” accusation represents a clever bit of bait: an invitation for community groups to deny the charge of being unions (as if that were a bad thing) and thereby enter into a potentially endless cycle of defending themselves from that charge. In fact, the relationships between traditional unions and low-wage/immigrant worker organizing groups vary greatly: some have no working relationships with unions, some work occasionally and amicably with unions, and others engage with unions quite frequently and even openly aspire to become more union-like.

But the broad-brush labeling of “worker centers” could have potential legal and regulatory consequences, too. The U.S. Chamber is using its reports–plus attack ads, articles from right-wing think tanks such as the Manhattan Institute, and op-eds in major newspapers echoing similar refrains—to persuade the public and the government that all low-wage and immigrant worker organizing groups should be subjected to the same financial reporting and internal structuring requirements that unions face. They aim to impose severe restraints on charitable contributions and to limit or ban secondary boycotts (among other activities). If their opponents are successful, the low-wage worker sector—including groups with no active relationships with unions—could be hobbled.

The Chamber is not only recycling anti-union tactics. In one particularly revealing statement in its first report, author Jarol Manheim compares the loose network of worker centers to the anti-poverty network ACORN, which was targeted and ultimately broken apart by right-wing attacks in the mid-2000s. Manheim names a foundation (Needmor) that supports “organizing to achieve social justice, and was once a major contributor to ACORN chapters in several communities. Between 2009 and 2011, its grantees included, among others, the Koreatown Immigrant Workers Association (KIWA).”27

This comparison of worker centers to ACORN may be a dogwhistle to business leaders that low-wage worker groups are vulnerable to the same take-down tactics, including pseudo-journalistic video exposés, congressional hearings, and public defunding. As Lee Fang pointed out in an April article in The Nation, the case of ACORN, which dissolved its national structure in 2010 in response to this onslaught, could be seen as a sort of cautionary tale for immigrant and low-wage worker organizing efforts: to avoid the same fate, they will need to recognize and strategically respond to this national threat.

Spread the word