This Wednesday was the last day of the third fundraising quarter for presidential campaigns, which means we got an inside look at how the candidates are doing—financially speaking.

Not surprisingly, Democratic frontrunner Hillary Clinton came out in front, having raised $28 million in the past three months—that’s more than any non-incumbent candidate ever and puts her on track to raise $100 million by the end of the year, according to a Clinton aide.

A bigger surprise (though maybe not for his avid supporters) was that Bernie Sanders, who has sworn off PAC money, declined to establish a super PAC, and heavily leans on small donations, has raised $26 million in his third-quarter fundraising haul. What’s more, Sanders held just seven fundraisers during that time, compared to Clinton’s 58—meaning that Sanders has had more time to spend face-to-face with voters, not big donors. And unlike Clinton, he hasn’t had to spend an outsized amount of campaign money hosting fancy fundraising dinners.

Sanders’s donors also are better positioned to keep on giving. “Because most of money is coming from small donors, the people giving can keep making $25 or $30 donations, unlike those who write $2,700 checks to Clinton’s campaign and can’t give again,” says Adam Smith, communications director for campaign-finance reform advocacy group Every Voice. “It’s like he’s daring the post-Citizens United regime. And if not for super PACs, he’d be lapping the Republicans.”

As the fund reporting deadline loomed, the Sanders campaign announced that it had surpassed the one-million-online-contribution threshold, which outpaces Barack Obama’s 2008 campaign by a solid four months. Those contributions have come from 650,000 individual donors. Clinton’s campaign has yet to clarify how many individual donors it has, but it claims that 93 percent of its donations were under $100. Still that says nothing of the remaining 7 percent, who are surely much closer to the $2,700 contribution maximum that Clinton heavily relies on.

“This means, first of all, that Sanders has an equivalent amount of campaign funds to wage a campaign and, secondly, has reached out to a much broader base of voters,” says Craig Holman, who advocates for campaign-finance reform for Public Citizen. “Sanders has developed a campaign on broad-based strength, much like what we saw from Obama in 2008.”

Campaign finance reform has become a marquee issue in the Democratic field—Bernie Sanders, Hillary Clinton, and Martin O’Malley have each called for a small-donor-matching public campaign-finance system for federal elections. A couple weeks ago, Clinton unveiled her campaign-finance reform plan, including small-donor matching. Bernie Sanders announced in August that he would introduce legislation that would institute public funding of elections. Both plans are short on details, like what a matching ratio would be, or what constitutes a “small donor.”

A logical starting point would be to look at Representative John Sarbanes’s Government By the People Act, which was endorsed today in Governor Martin O’Malley’s campaign-finance reform plan. The bill would match every donation to congressional candidates of $150 or less to the tune of a 6-to-1 ratio—or 9-to-1 if a candidate agreed to take only small-donor contributions. Public matching systems like this have proven successful at enabling candidates with few big-money supporters to win public office in places like New York City and Los Angeles.

“The purpose of small-donor public funding systems is to encourage small donors to participate,” says Larry Noble, senior counsel at the Campaign Legal Center. “When people give even a small amount, they’re more involved and more likely to vote.”

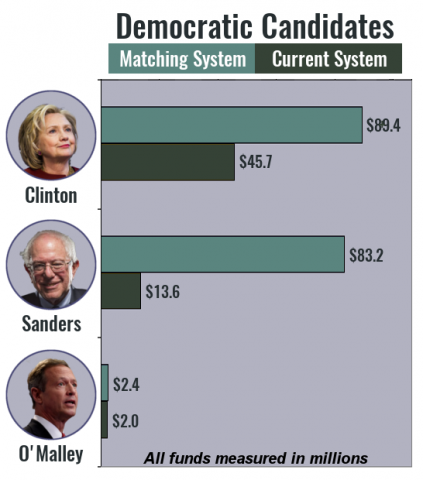

So, hypothetically, how would the fundraising dynamics shift in the Democrats’ presidential race if the candidates were using the campaign-finance system that they themselves call for?

There’s substantial evidence that under such a system, Bernie Sanders would be the fundraising frontrunner.

As a recent U.S. Public Interest Research Group report showed, in the previous fundraising quarter—April through June—77 percent of the contributions to his campaign were under $200, compared to just 18 percent for Clinton, who outraised Sanders three-to-one during that period. The report finds that if a small-donor matching system had been in place, Sanders would have only been 7 percent behind Clinton.

Courtesy of U.S. PIRG

Second quarter fundraising (April-June).

Given the U.S. PIRG analysis of the numbers from the previous quarter, in which Sanders raised far less money than Clinton, it’s safe to say that this go-around he would be ahead of Clinton in fundraising totals.

“If a matching system existed, there’s no question that Bernie would come out on top on the money race,” Every Voice’s Smith says. “But more importantly, it would incentivize candidates to focus their efforts on small-donor cash.”

Comparing Sanders’s surprising surge to that of Obama’s in 2008 makes for a nice political narrative—both took on the same establishment heavyweight; both tapped into unprecedented new small-donor bases; both injected something new and refreshing into the political discourse.

But as Holman notes, there’s one big difference between 2008 and 2016: super PACs. Sanders has pledged to refuse any support from a super PAC. Clinton, however, has a robust network of outside spenders that she can count on to plaster the airwaves with ads. The pro-Clinton super PAC Priorities USA Action has raised $40 million so far—$25 million coming in just the past three months.

“The amount of money that will be spent in the 2016 elections will overwhelm the 2008 figures, and Big Money has never been more important than today,” Holman says. “While Sanders is showing phenomenal strength, he still has a very tough road ahead.”

Justin Miller is a writing fellow for The American Prospect. Follow him on Twitter: @by_jmiller

Spread the word