This column was written by Glenn Greenwald for the Guardian's newspaper edition

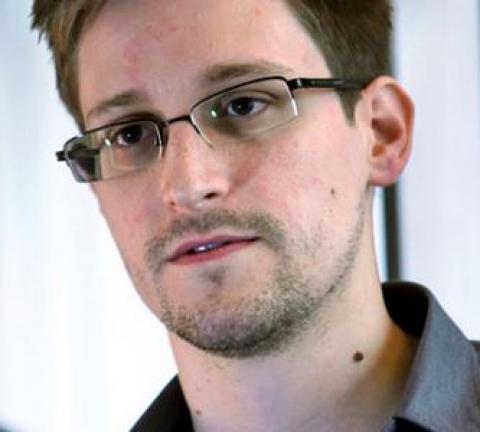

In my first substantive discussion with Edward Snowden, which took place via encrypted online chat, he told me he had only one fear. It was that the disclosures he was making, momentous though they were, would fail to trigger a worldwide debate because the public had already been taught to accept that they have no right to privacy in the digital age.

Snowden, at least in that regard, can rest easy. The fallout from the Guardian's first week of revelations is intense and growing.

If "whistleblowing" is defined as exposing secret government actions so as to inform the public about what they should know, to prompt debate, and to enable reform, then Snowden's actions are the classic case.

US polling data, by itself, demonstrates how powerfully these revelations have resonated. Despite a sustained demonization campaign against him from official Washington, a Time magazine poll found that 54% of Americans believe Snowden did "a good thing", while only 30% disagreed. That approval rating is higher than the one enjoyed by both Congress and President Obama.

While a majority nonetheless still believes he should be prosecuted, a plurality of Americans aged 18 to 34, who Time says are "showing far more support for Snowden's actions", do not. Other polls on Snowden have similar results, including a Reuters finding that more Americans see him as a "patriot" than a "traitor".

On the more important issue – the public's views of the NSA surveillance programs – the findings are even more encouraging from the perspective of reform. A Gallup poll last week found that more Americans disapprove (53%) than approve (37%) of the two NSA spying programs revealed last week by the Guardian.

As always with polling data, the results are far from conclusive or uniform. But they all unmistakably reveal that there is broad public discomfort with excessive government snooping and that the Snowden-enabled revelations were met with anything but the apathy he feared.

But, most importantly of all, the stories thus far published by the Guardian are already leading to concrete improvements in accountability and transparency. The ACLU quickly filed a lawsuit in federal court challenging the legality, including the constitutionality, of the NSA's collection of the phone records of all Americans. The US government must therefore now defend the legality of its previously secret surveillance program in open court.

These revelations have also had serious repercussions in Congress. The NSA and other national security state officials have been forced to appear several times already for harsh and hostile questioning before various committees.

To placate growing anger over having been kept in the dark and misled, the spying agency gave a private briefing to rank-and-file members of Congress about programs of which they had previously been unaware. Afterward, Democratic Rep Loretta Sanchez warned that the NSA programs revealed by the Guardian are just "the tip of the iceberg". She added: "I think it's just broader than most people even realize, and I think that's, in one way, what astounded most of us, too."

It is hardly surprising, then, that at least some lawmakers are appreciative rather than scornful of these disclosures. Democratic Sen Jon Tester was quite dismissive of the fear-mongering from national security state officials, telling MSNBC that "I don't see how [what Snowden did] compromises the security of this country whatsoever". He added that, despite being a member of the Homeland Security Committee, "quite frankly, it helps people like me become aware of a situation that I wasn't aware of before".

These stories have also already led to proposed legislative reforms. A group of bipartisan senators introduced a bill which, in their words, "would put an end to the 'secret law' governing controversial government surveillance programs" and "would require the Attorney General to declassify significant Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court (FISC) opinions, allowing Americans to know how broad of a legal authority the government is claiming to spy on Americans under the Patriot Act and Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act".

The disclosures also portend serious difficulties for the Director of National Intelligence, James Clapper, and NSA chief, Keith Alexander. As the Guardian documented last week, those officials have made claims to Congress – including that they do not collect data on millions of Americans and that they are unable to document the number of Americans who are spied upon – that are flatly contradicted by their own secret documents.

This led to one senator, Ron Wyden, issuing a harshly critical statement explaining that the Senate's oversight function "cannot be done responsibly if senators aren't getting straight answers to direct questions", and calling for "public hearings" to "address the recent disclosures and the American people have the right to expect straight answers from the intelligence leadership to the questions asked by their representatives".

One well-respected-in-Washington national security writer, Slate's centrist Fred Kaplan, has called for Clapper's firing. "It's hard," he wrote, "to have meaningful oversight when an official in charge of the program lies so blatantly in one of the rare open hearings on the subject."

The fallout is not confined to the US. It is global. Reuters this week reported that "German outrage over a US Internet spying program has broken out ahead of a visit by Barack Obama, with ministers demanding the president provide a full explanation when he lands in Berlin next week and one official likening the tactics to those of the East German Stasi."

Indeed, Viviane Reding, the EU's justice commissioner, has, in the words of the New York Times, "demanded in unusually sharp terms that the United States reveal what its intelligence is doing with personal information of Europeans gathered under the Prism surveillance program revealed last week". She is particularly insistent that EU citizens be given some way to find out whether their communications were intercepted by the NSA.

In the wake of the Guardian's articles, I heard from journalists and even government officials from around the world interested in learning the extent of the NSA's secret spying on the communications of their citizens. These stories have resonated globally, and will continue to do so, because the NSA's spying apparatus is designed to target the shared instruments used by human beings around the world to communicate with one another.

The purpose of whistleblowing is to expose secret and wrongful acts by those in power in order to enable reform. A key purpose of journalism is to provide an adversarial check on those who wield the greatest power by shining a light on what they do in the dark, and informing the public about those acts. Both purposes have been significantly advanced by the revelations thus far.

Twitter: @ggreenwald

Spread the word