Media Bits & Bytes - Supersize Learning to Live On-line edition [Glad to be back after 2 weeks!]

- Don't Worry About Getting Hacked. Worry About Getting Socially Engineered - Caitlin Dewey (Washington Post)

- The Laborers Who Keep Dick Pics and Beheadings Out of Your Facebook Feed - Adrian Chen (Wired)

- From Miasma to Ebola: The History of Racist Moral Panic Over Disease - Stassa Edwards (Jezebel)

- The Future Of The Culture Wars Is Here, And It's Gamergate -Kyle Wagner (Deadspin)

- Building Networks and Working Partnerships with Creatives - Tracy Van Slyke (from Spoiler Alert)

- Facebook has Totally Reinvented Human Identity: Why it's Even Worse than You Think - Susan Cox (Salon)

- Wireless Carriers are Rolling Out a Horrible New Way to Track You - Russell Brandom (The Verge)

Don't Worry About Getting Hacked. Worry About Getting Socially Engineered

By Caitlin Dewey

October 15, 2014

Washington Post

In some respects, today's most dangerous online scams are not terribly different from the Nigerian-prince e-mails of old. But modern "social engineering," or "social hacking," as practitioners call it, is far subtler and more sophisticated than Nigerian princes ever were. The definition is considerably broader, too: Social engineering describes any technique that tries to get around a security system - not by breaking or attacking the system itself, but by exploiting vulnerabilities in the people who use it.

Those "vulnerabilities" can range from the obviousness of your passwords to the manipulability of your feelings. That also means scammers aren't just sending e-mails any more. They compile reams of personal data based on information gleaned from public records, social media and Google search. And once they've cracked those, your world is their oyster: On anonymous forums like AnonIB, or in black-backgrounded pages on the Dark Web, social engineers trade everything from nude photos to Social Security numbers and credit card details. Complained one user in Reddit's social engineering thread: "Most `hackers' these days are just glorified social engineers."

The Laborers Who Keep Dick Pics and Beheadings Out of Your Facebook Feed

By Adrian Chen

October 23, 2014

Wired

The campuses of the tech industry are famous for their lavish cafeterias, cushy shuttles, and on-site laundry services. But on a muggy February afternoon, some of these companies' most important work is being done 7,000 miles away, on the second floor of a former elementary school at the end of a row of auto mechanics' stalls in Bacoor, a gritty Filipino town 13 miles southwest of Manila. Past the guard, in a large room packed with workers manning PCs on long tables, I meet Michael Baybayan, an enthusiastic 21-year-old with a jaunty pouf of reddish-brown hair. Baybayan's screen does not resemble typical startup work: It appears to show a super-close-up photo of a two-pronged dildo wedged in a vagina. I say appears because I can barely begin to make sense of the image, a baseball-card-sized abstraction of flesh and translucent pink plastic, before he disappears it with a casual flick of his mouse.

Baybayan is part of a massive labor force that handles "content moderation"-the removal of offensive material-for US social-networking sites. Social media's growth into a multibillion-dollar industry, has depended in large part on companies' ability to police the borders of their user-generated content-to ensure that Grandma never has to see images like the one Baybayan just nuked.

So companies like Facebook and Twitter rely on an army of workers employed to soak up the worst of humanity in order to protect the rest of us. And there are legions of them-a vast, invisible pool of human labor.

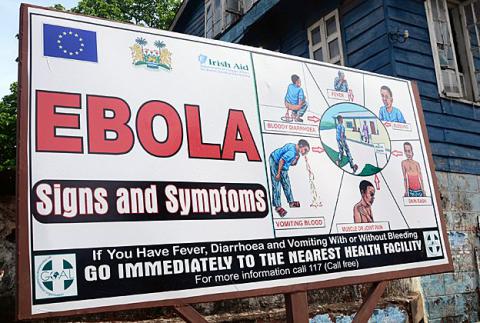

From Miasma to Ebola: The History of Racist Moral Panic Over Disease

By Stassa Edwards

October 14, 2014

Jezebel

On October 1st, the New York Times published a photograph of a four-year-old girl in Sierra Leone. In the photograph, the anonymous little girl lies on a floor covered with urine and vomit, her eyes are glassy, returning the photographer's gaze. The photograph is tightly focused on her figure, but in the background the viewer can make out crude vials to catch bodily fluids and an out-of-focus corpse awaiting disposal.

The photograph, by Samuel Aranda, accompanied a story headlined "A Hospital From Hell, in a City Swamped by Ebola." Aranda's photograph is in stark contrast to the images of white Ebola patients that have emerged from the United States and Spain. In these images the patient, and their doctors, are almost completely hidden; the suffering is invisible, these photographs are meant to reassure Westerners that sanitation will protect us, that contagion is contained.

Pernicious undertones lurk in these parallel representations of Ebola, metaphors that encode histories of nationalism and narratives of disease. African illness is represented as a suffering child, debased in its own disease-ridden waste; like the continent, it is infantile, dirty and primitive. Yet when the same disease is graphed onto the bodies of Americans and Europeans, it morphs into a heroic narrative and the mastery of modern technology over contaminating, foreign disease. These parallel representations work on a series of simple, historic dualisms: black and white, good and evil, clean and unclean.

The Future Of The Culture Wars Is Here, And It's Gamergate

By Kyle Wagner

October 14, 2014

Deadspin

Over the weekend, a game developer in Boston named Brianna Wu fled her home after an online stalker vowed to rape and kill her. She isn't the first woman who's been forced into hiding by aggrieved video game fans associated with Gamergate, the self-styled reform movement that's become difficult to ignore over the past several months and she probably won't be the last.

By design, Gamergate is nearly impossible to define. It refers, variously, to a set of incomprehensible Benghazi-type conspiracy theories about game developers and journalists; to a fairly broad group of gamers concerned with corruption in gaming journalism; to a somewhat narrower group of gamers who believe women should be punished for having sex; and, finally, to a small group of gamers conducting organized campaigns of stalking and harassment against women.

Really, though, Gamergate is exactly what it appears to be: a relatively small and very loud group of video game enthusiasts who claim that their goal is to audit ethics in the gaming-industrial complex and who are instead defined by the campaigns of criminal harassment that some of them have carried out against several women. In many ways, Gamergate is an almost perfect closed-bottle ecosystem of bad internet tics and shoddy debating tactics. It's a fascinating glimpse of the future of grievance politics as they will be carried out by people who grew up online.

Building Networks and Working Partnerships with Creatives

By Tracy Van Slyke

November 2014

Spoiler Alert: How Progressives Will Break Through With Pop Culture

On March 11, 2014, FunnyorDie.com released a new video as part of its hit web series Between Two Ferns. With comedian and Hangover actor Zach Galifianakis as the semi-dumb and cringe-inducing host, these videos were known for their skewering and hilarious Hollywood celebrity interviews.

But this video was different. This video featured a different kind of celebrity: President Barack Obama. While known for his "cool" factor of fist bumps and Jay Z shoulder brushes during the presidential campaign, it was far more normal to see him in a presidential sit-down with 60 Minutes or CNN than a snarky web-based comedy show.

Obama was making a play to reach young people-the target audience of Between Two Ferns-as part of the effort to promote the Affordable Care Act to that demographic. While allowing Galifianakis to get his potshots in, Obama was also able to spread his message about the ACA.

Funny or Die became the number one source of referrals to Healthcare.gov. As of 3:30 p.m. on the day it was posted, the video had accumulated 5.9 million views, and 19,000 viewers had continued to Healthcare.gov. Twenty-four hours after the video was posted, more than 13 million people had viewed it, and 54,000 had gone on to visit Healthcare.gov. In its essence, it was a concrete example that points to how progressives need to build strong relationship networks and working partnerships with creatives.

Facebook has Totally Reinvented Human Identity: Why it's Even Worse than You Think

By Susan Cox

October 26, 2014

Salon

Facebook has redefined the standard of what information should be immediately known about you as a person. Facebook can even reduce your personal journey on this earth to a chronological list of "Life Events." It knows the true measure of what's important in this crazy world and can tell you everything noteworthy that's happened to you in this one helpful list. Facebook has turned our lives inside out to the point where all of this very specific information now seems to be what constitutes a social identity.

What was once nebulous and unknown about a life is now defined and categorized in this culture of hyper-transparency. It is little wonder why the journalistic coverage of Facebook's recent "real name policy" scandal was as uncritical as it was in accepting of Facebook's legitimate right to the verification of users' legal names.

There are great ideological stakes when asking, "What is your real name?" We are essentially asking: "What definitively constitutes a person?" Historically, identification technologies have served to consolidate people as objects of knowledge into discrete political units. Their regulation is then easily rationalized and demonstrably justified. The question of what should be done with you is much easier to answer when we can definitively say what you are.

Wireless Carriers are Rolling Out a Horrible New Way to Track You

By Russell Brandom

October 28, 2014

The Verge

Last week, privacy advocates turned up some unsettling news: for two years, Verizon's Precision Insights division has been seeding web requests with unique identifiers. If you visited a website from a Verizon phone, there's a good chance the carrier injected a special tag into the data sent from you phone, telling the website exactly who you were and where you were coming from, all without alerting customers or informing the public at large. oday, Forbes' Kashmir Hill reports that AT&T is testing a similar program, although it may be possible to opt out. In both cases, the message is clear: there's a lucrative business in tracking users across the web, and carriers want in on it.

Spread the word