When 72-year-old James Gustave Speth was growing up in tiny Orangeburg, South Carolina - population 13,000 - the town was completely segregated. But if you were a white kid and didn't look very closely, Speth writes, in Angels by the River, life seemed idyllic. "There was little crime in my world, little alcohol, no drugs, no social media, and even no TV until about the time of the Army-McCarthy hearings before Congress in 1954. We had plenty of sports, young romance, cars and cruising, movies and drive-ins, Protestant religion, parties, hunting and fishing, and I would say, schooling."

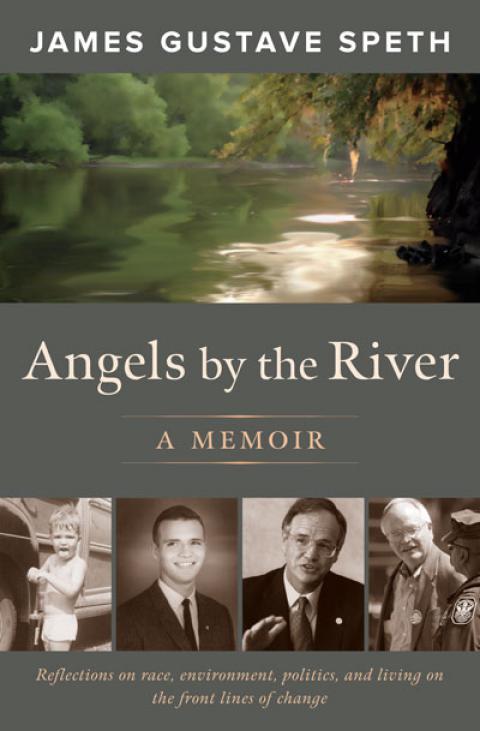

Angels by the River: Reflections on Race, Environment, Politics, and Living on the Frontlines of Change

By James Gustave Speth

Chelsea Green Publishing, 206 pages,

Hardcover: $25

October 21, 2014

ISBN-13: 9781603585859 ISBN-10: 1603585850

As a middle-class white kid, Speth didn't know that his birthplace was actually 60 percent Black and that tenant farming and sharecropping left the majority of his African-American neighbors in abject poverty. This included people Speth cared about deeply, for like many Caucasian southerners, he and his siblings were reared with the help of two devoted Black nannies. Still, he writes that it took him years to realize that they were "spending more time with the Speth children than with their own families." It also took him years to understand that the foul smell he noticed at the lake near his grandparents' North Carolina home was not natural, but was instead caused by a toxic brew of chemicals that were routinely dumped by a local tannery, a rayon plant and a paper mill.

Coming of age meant coming to terms with these realities, but it was slow going, and Speth admits that as a teenager he was more concerned with playing football and getting into a good college than he was with politics. This began to change when he moved north to attend Yale University in 1960.

One incident, when he was a newly-arrived, first-year student, was particularly impactful. Speth writes that he was studying in a seminar room when he was approached by two white upperclassmen. One of them forcibly grabbed him and slammed him against the wall. The assailant then angrily growled: "If you ever say nigger or any other racist shit, we will beat you to a pulp, understand?" Speth writes that the encounter was completely unprovoked. "Somehow they identified me as a southern white boy" who might be a bigot, he recalls.

Needless to say, he was unsettled by the attack, but notes that he did not react defensively. Instead, he reports that because the confrontation occurred just as pro-integration sit-ins were beginning, he felt morally compelled to support the burgeoning civil rights struggle as well as the just-formed Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. What's more, as a political science major, his classes delved into texts about equity, independence and liberty, themes that rattled his ideas about race, class and power.

He ultimately came to understand that he and his friends and family had, wittingly and unwittingly, "accepted and perpetuated a monstrous injustice toward African Americans and that the great bulk of what I had come to believe was nonsense or worse. Yet, when one's worldview and the institutions one believes in collapse, it can be, I found, entirely liberating . . . I was not wise, I had learned, to critically accept the status quo. The unmooring, breaking free of the past, was the first big step along a path that would lead me far away from my conservative southern roots to a place that no longer fits comfortably on the spectrum of mainstream American politics."

Nonetheless, there were many conventional, if high-powered stopovers on the road to this more-radical destination. The founder of the Natural Resources Defense Council and the World Resources Institute, Speth got his start as clerk to Supreme Court Justice Hugo Black. He also served as chair of the US Council on Environmental Quality under President Jimmy Carter; was administrator of the United Nations Development Programme; and served as dean of the Yale School of Forestry and Environmental Studies. His books include Red Sky at Morning: America and the Crisis of the Global Environment; The Bridge at the Edge of the World; Capitalism, the Environment and Crossing from Crisis to Sustainability; and American the Possible: Manifesto for a New Economy.

It's certainly an impressive personal resume, but while Speth's memoir notes his accomplishments, much of Angels by the River is focused on all that remains to be done to win environmental justice. While much of the book can be read as an indictment of racism, he focuses his recommendations and critique on the mainstream environmental movement he helped create. He is especially critical of the many environmental organizations that have grown exponentially since the first Earth Day in 1970, and concedes that they have achieved few of their stated aims. "The prospect of a ruined planet is now very real," he writes. "We have won many victories but we are losing the planet."

The blame, he writes, at least partially rests with overreliance on legislation, the writing of new laws that has drawn environmental groups into the DC Beltway. As a result, Speth believes that work on the state and local levels has been neglected. More damaging, he continues, is the mistaken assumption that "good faith compliance with the law will be the norm and that corporations can be made to behave." Even more dastardly, he adds, is that by succumbing to the temptation to become players in the halls of Congress, many advocates of environmental sanity have allowed themselves to make compromises that are mealy-mouthed if not overtly toothless.

"Today's environmentalism is not focused strongly on political activity or grassroots political movement," he concludes. "Electoral politics and movement building have played second fiddle to lobbying, litigation and working with government agencies and corporations."

Despite the valiant efforts of groups like 350.org, Speth makes clear that today's environmentalists can't stop climate change or pollution without taking on "the creeping plutocracy and corporatocracy we face - the ascendancy of money power and corporate power over people power."

This, of course, is exactly right. At the same time, while Speth's naming of the problem is spot-on, he is weak on solutions. For example, how can we sustain vital local economies and move away from what he calls "the growth fetish" of unbridled capitalism to establish and maintain ecological well-being and democratic governance? How can we convince hard-working Americans that rampant consumerism is absurd and that mindful consumption, "from more to enough," is necessary? How can we shift from a belief system in American exceptionalism, or move from what Speth dubs "hard power to soft, from military prowess to real security?"

They're great questions, and I have no answers. Sadly, Speth, himself, offers few clues, but the conundrums he poses need to be addressed by environmental activists.

That said, by enumerating the enormous challenges we face, Speth has issued a clarion call to those who want the earth to keep spinning. In addition, by weaving his personal story into a political narrative, Angels by the River offers an inspiring glimpse into the power each individual has to craft a meaningful and principled life. And while Speth credits numerous "angels by the river" who pushed, prodded and poked him to dig deeply and imagine a better world, his writing and thinking do the same for his readers. He, in turn, may be the angel of our better natures, reminding us that the stakes of inaction will be monumental.

[Eleanor J. Bader teaches English at Kingsborough Community College in Brooklyn, NY. She is a 2015 winner of a Project Censored award for "outstanding investigative journalism" and a 2006 Independent Press Association award winner. The coauthor of Targets of Hatred: Anti-Abortion Terrorism, she presently contributes to Lilith, RHRealityCheck.org, Theasy.com and other progressive feminist blogs and print publications.]

Thanks to the author for sending her review to Portside.

Spread the word