Background and Early Years

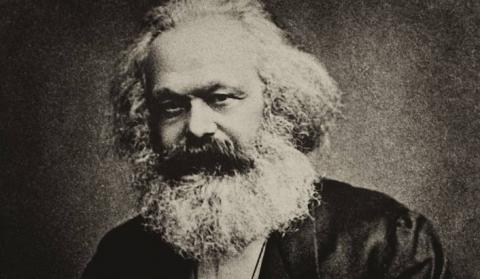

Karl Marx, who developed the philosophy of dialectical and historical materialism, scientific and political economy, the founder of scientific socialism and communism, and teacher and leader of the international working class for whom he created a new, purposeful world outlook, was born at Trier, in the Prussian Rhineland, on May 5, 1818. One must include Frederick Engels (1820-1895), his closest friend and collaborator, born in Germany two years later. It was some 50 years before Germany became a unified state.

Karl Marx’s father was a Jewish lawyer who when the young boy was six years old converted to Protestantism, for pragmatic career reasons given the constraints on those of Judaic belief. Karl Marx came from a learned and cultured background where the quest for knowledge was fostered at an early age. At university he studied law, majoring in history and philosophy.

Of radical humanist disposition, Marx was drawn into the circle of Leftist Hegelians who sought to draw revolutionary atheistic conclusions from their philosophy teacher Georg Hegel’s idealistically based concept of dialectics. To them Hegel contentiously recognised a world in motion but with the spirit or idea rather than matter being seen as primary. The fundamental question of philosophy being what is primary: consciousness or being – mind or matter? It was his attraction to the materialistic anti-theological teachings of another German philosopher, Ludwig Feuerbach, seeing consciousness created and propelled by material forces, leading to Marx’s groundbreaking development of dialectical and historical materialism as his ultimate philosophical foundation. Such synthesis is vitally relevant to understanding any age. South African Marxists among other things, for instance, need to consider how best to counter harmful superstitious beliefs and practices, promoted by those in high office hiding their own backwardness and political machinations by false declarations in defence of their “culture” which as often as not they are deliberately distorting?

Marx was initially interested in pursuing an academic career. However the reactionary measures of the Prussian authorities against open-minded academics caused him to abandon such a vocation and he turned instead to journalistic activity. By 1842 he had joined the staff of the radical democratic Rheinische Zeitung, and soon became its editor which began his run-in with the Prussian censors and political police.

The Age of Revolution 1789-1848

Marx and Engels grew up in tumultuous times which shaped them. Their transition from revolutionary democrats to communism was brought about by the class struggles in Europe where of course capitalism and hence its socialist protagonist consequently first emerged. This by the way is why we should not fall into the trap of regarding Marx as Eurocentric for Marxism spread everywhere and was adapted to suit national conditions by revolutionaries all over the world. Marx’s active participation in the revolutionary struggle first in Germany and then in France where he fled from persistent persecution; his study of political economy, utopian socialism and history; his polemics with anarchists whose numbers rose dramatically as landless peasants entered the ranks of the proletariat; Blanquist plotters believing assassination and the seizure of power by the armed putsch as the sole means of affecting change; and petty bourgeois socialists of all stripes; was instrumental in honing his powers of critical analysis and development. Marx’s experience and application led him to develop his theory of historical materialism, the extension of materialism into social phenomenon embracing the activities of the masses, history being governed by definitive laws, the class struggle as the main spring of events. As declared in theCommunist Manifest: “The history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles.” Engels later corrected this to exempt the “pre-history” primitive communal systems all over the world in which private property was unknown.

The Marxist writer, Eric Hobsbawm’s book of the period, The Age of Revolution 1789-1848 covered the dual revolutions in Europe which changed the world: the French political revolution and the English industrial revolution. These cast the mould of the 19th and 20th century (foundations of the colonial system and rise of imperialism as the highest stage of capitalism as analysed by Lenin) and spanned the 60 years from the great French Bourgeois Revolution of 1789 (which changed the face of feudal Europe) to the outbreak of further revolutionary waves of struggle in France, Belgium, Germany, Austria, Poland, Hungary, Italy, Spain, Portugal, Russia climaxing in the stormy years of 1848-49. The Arab Spring of 2012, military intervention and triumph of counter-revolution particularly in Egypt, has been likened to this period. Could a counter-revolutionary turnaround be the fate of South Africa’s Spring of 1994, and our national democratic revolution as class contestation sharpens over the vital questions of the control and direction of the economy and distribution of wealth? We study the past and its lessons to assist in understanding the general features laid bare by Marx as a guide in our own time and place.

Marx was born a mere 29 years after the onset of the French Revolution, the climax of which was 1792-94, when Jacobin radical forces represented by the likes of Danton and Robespierre were driving the bourgeois revolution forward. The execution of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette, after they sought to join the émigré forces of the counter-revolution deploying outside France’s borders, led to the establishment of the first republic. The Reign of Terror ended with the revolution “devouring its own children”, as Jacobin leaders representing different tendencies followed the monarch to the guillotine. Bourgeois order emerged triumphant on the bayonets of Napoleon Bonaparte’s armies. All this amid the class struggles and national revolts, breathtaking scientific and technological advances, industrial revolution, emergence of the proletariat in the so-called age of “reason and rationality” with a reach as far as the distant slave revolt in French Haiti led by Toussaint Louverture which showed that colonial slaves could be instruments of change and not mere bystanders of Europe’s revolutions. Such developments were not ignored by Marx.

Born Frees

To use South African terminology, Marx and Engels were “born frees” in the era following the French Revolution. In Wordsworth’s poetic phrase: “bliss it was to be alive” at that dawn of human emancipation. And so it was in our 1994 transition to democracy. The inspirational effect of such tumultuous times on youthful, radical minds was immense. It is worthy to note that Marx and Engels did not use their education and opportunities for self advancement and personal prosperity, their own careers sacrosanct, but in a lifetime of sacrifice and service in the proletarian struggle for socialism and the advance of humanity. Theirs was service in the cause whose objective was the fullest realisation of those great slogans of the French Revolution – “Liberty, Equality, Fraternity” – not merely freedom for the ruling propertied classes but economic equality for all and a fraternity which was thoroughly internationalist:

“Workers of the world unite you have nothing to lose but your chains”, which spoke to all nations and people of all pigmentation suffering the multiple oppression of race, class and colonial subjectivity. The issues of race and colonisation, often referred to as the national question, occupied Marx’s attention. He developed his views with his study of capital and its globalisation. This became key to analysis in the 20th century age of imperialism, particularly developed by Lenin, and the anti-colonial liberation struggles of Africa, Asia, Latin America whose movements and communist parties grappled with a theory of the nexus of class and nation (including ‘race’), and the development of strategy and tactics in the national democratic revolutions to come.

That issue of not simply formal political freedom and independence, but with it real equality – and that is economic and class based at root – has swiftly come to the fore in South Africa post the 1994 democratic breakthrough and with it current problems of the national democratic revolution. It all boils down to the question of which class, which social forces, lead the struggle. If the character of the outcome of the national liberation struggle is socialist in orientation rather than bourgeois nationalist then the working class must be in the ascendency. And as Marx showed it is the capitalist mode of production which brings into existence the working class and the socialisation of the means of production. The more developed the economy and industry the more advanced the social class formations of society. Such objective conditions make it more possible for the working class to lead the struggle which was why there were high expectations that a socialist outcome was possible in South Africa.

Marx and Engels sought that age of rationality in which exploitation and classes would cease to exist, along with oppressive social, national, religious and exploitative cleavages along gender, patriarchal, ethnicity and race lines – all such antagonistic divisions resulting from class based society with an extreme form of race domination and exploitation in the colonies. The upsurge of race, gender and identity politics particularly in our universities and taking hold of our youth in general, unemployed, marginalised and betrayed, need to be aligned with the fundamental class issues enunciated by Marx and Engels as their body of theories developed.

Marx and Engels became progressively taken up with questions of nationalism, the nation state and the conditions in the underdeveloped world, under the heel of colonialism, conditioned by the uneven development of capitalism. It is to be noted that while Marx in his earlier years reflected a limited appreciation of developments in India and China, as well as Africa, these did not escape him, as seen for example in the Communist Manifesto and in his support for the Indian revolt of 1857 put down with horrific savagery by English troops. In later years he was correcting his earlier shortcomings:

“The English jackasses need an enormous amount of time to arrive at an even approximate understanding of the real conditions of … conquered groups,” he wrote in 1879. (See Kolja Lindner’s “Marx’s Eurocentraism”, Radical Philosophy, 2010), Marx’s tributes to Native Americans or the people of India testify to the broadness and depth of his affiliation. His work demonstrates his core respect for the humanity and socialist potential within pre-capitalist social relations and can be attested to in his grappling with the national question, both in the legacy of a feudally fragmented Europe and the conditions of the indigenous peoples of the colonised world.

In fact, even closer to home, any shortcomings in his early assessments were there to be corrected. His young daughter Eleanor arguably prompted both Marx and Engels to appreciate the role of the Irish Fenian nationalists in their resort to arms against the English colonisers when they thought this counterproductive believing Irish freedom would come from a socialist England – shades of South Africa’s communists in the early 1920s believing the organised white working class were the leading force for a socialist revolution which would then free the indigenous, largely rural, black people. (“Eleanor Marx”, a biography by Rachel Holmes, chapter 6 “Fenian Sister”). What Marx and Engels were perfectly clear and consistent about from that start was that “a people that oppresses other people cannot itself be free”. The proposition is fundamental to workers and oppressed people of all lands and is an abiding tenet of international solidarity.

Marx’s reworking of his views on Ireland represent an important development in his views of the relationship between oppressor and oppressed nations and a key starting point for the Marxist-Leninist theorisation on the rights of nations to self determination and national liberation struggles. Our country is particularly rich in this theory and practise, pioneered by the communist party, and hotly contested by other trends of socialist though in the polemic around concepts such as “colonialism of a special type”, so-called “two stages of struggle” and the the “national democratic revolution”. (The forthcoming 25 May colloquialism on “The National Question” will focus on these issues which are clearly of key relevance to an understanding of where we are and the way ahead for the South African revolution at this critical juncture). The central question here is the correlation between class and national struggles and whether the outcome in the national democratic revolution will see victory for workers or capitalists.

The point is to change the world

From the outset of adulthood Marx lived by one of his famous dictums: “The philosophers have hitherto sought to interpret the world, the point however is to change it.”

Marx’s life is a model for revolutionaries today. Revolutionary theoretician, activist, journalist, organiser of the Communist League and Workingmen’s Associations, culminating in establishment of the First International (1864-1872), Marx was pursued by the secret police of several countries, deported from Germany, France and Belgium, with the ebb and flow of revolution and counter-revolution. The journals he founded were successively banned and he ended up from 1849 an exile in London for 34 years until the end of his life in 1883. It was there in the comparatively more tolerant bourgeois democracy of Britain, (albeit the ferocious exploitation of labour in that country, vicious colonial oppressor in Ireland, Africa and Asia from where the British Empire extracted its vast wealth and resources – from the time of the slave trade – so integral to the emergence of capitalism and England’s world domination), where Marx commenced his monumental work on political economy and the workings of Capital, toiling away in that prestigious centre of learning, the newly opened Library of the British Museum. He showed how such opportunities provided by bourgeois democracy could be put to good use.

The Communist Manifesto

Marx and Engels’ co-authorship of the Communist Manifesto in 1848 (drawn up at the request of the Communist League and written at speed the previous year) was destined to become the second best-selling book of all time right across the globe. In it they enunciated their concept of dialectical and historical materialism, the theory and tactics of class struggle and the revolutionary role of the proletariat, for which their work and involvement of the preceding half-dozen years had prepared them. This included the necessity of alliances, particularly with the poor peasantry, and the elaboration of methods of struggle, from parliamentary nonviolence in a bourgeois democracy, sustained trade union and working class organisation and education, and depending on appropriate conditions the art of insurrection. This latter topic, and the role of armed struggle generally, came to the fore in southern Africa and elsewhere in the 1960s where repression made change through nonviolent struggle impossible, and favourable conditions materialised for guerrilla movements.

It is astonishing to realise that Marx was not yet 30 and Engels 28 when they wrote the Manifesto! Such was their maturity, discipline, knowledge and commitment that revolutionary thinkers and working class activists years older acknowledged their leadership. Virtually before the ink was dry the revolutions they predicted had spread like wildfire throughout Europe.

This question of age and the ability to lead remains pertinent in struggles to this day. So does another observation we can make and that is that revolutionary intellectuals, capable of combining theory with practice, can play a significant role in working class struggles. This is not to negate the very Marxian recognition that it is the working class that must lead the struggle for the emancipation of labour, and of society, for the socialist and communist future. This has been a big factor in South Africa’s ongoing revolution, the challenges of which are being hotly contested in practice particularly at a stage following the broad church of national liberation in which the class issues are now becoming sharper and more evident as witnessed in the Marikana massacre of striking miners in August 2012. Some have made reference to a “Faustian Pact” of trading political power in 1994 at the expense of economic and property compromises with regard to the dropping of nationalisation of the commanding heights of the economy and land ownership by the ANC (clauses 3 and 4 of the Freedom Charter) which has also fostered the rise of Julius Malema and the Economic Freedom Fighters. (See Sampie Terreblanch’s “Lost in Transformation”, Hein Marais “South Africa Limits to Change” and writings of Patrick Bond among others and my Introduction to the 4th edition of my memoir “Armed & Dangerous”, Jacana Publication 2013).

The commanding role of the working class is the very essence of the Communist Manifesto. From the onset of the bourgeois democratic revolutions of the late 18th to mid 19th Century (1789-1848), the emergent proletariat had played a remarkable role in what were to become the leading capitalist countries of Europe under conditions that suited the ascendant bourgeoisie in the victory over the feudal order in which the labouring masses, urban and rural, were opportunistically used, betrayed, feared, kept in check, driven back and where necessary mercilessly shot down in droves. We have seen this process all too often in post-independence Africa, Asia and Latin America and it has persisted in Europe (for example the Bloody Sunday massacre by British troops in Northern Ireland in 1972).

The Communist Manifesto identified the emergent class of wage labourers, the proletarians who had nothing to sell but their labour power, and nothing to lose but their chains, as the rising class, the “grave diggers of capitalism”, who would be the motive force in the struggle for advancing democracy through the national bourgeois revolution to the creation of a scientific socialist and ultimately communist society. In disclosing the historic role of the proletariat, Marx arrived at the inevitability of the social revolution and the necessity of providing the working class movement with a scientific world outlook. Marx and Engels recognised that the 1848-9 European revolutions were both bourgeois-democratic revolutions and struggles for national liberation or unification – Germany, Italy, Hungary, Poland.

The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte (1852)

Marx kept abreast of revolutionary developments of his time and provided outstanding journalistic accounts, the quality of which derived from his mastery of historical materialism as though he himself was at the very centre of events. Of particular note is his writings on “The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte” (first published in 1852 after Napoleon Bonaparte’s upstart nephew seized power) and “The Paris Commune” (published May 30th, 1871 by the International Workingmen’s Association as The Civil War in France).

Marx’s title for his searing analyses of Louis Bonaparte’s seizure of power in 1851 – following the revolution of February 1848 which had cast out the monarchy re-imposed in 1830 – was a mocking comparison between Louis, a mediocre nephew, and his iconic uncle Napoleon Bonaparte and the class interests they represented. Half a century before Napoleon had swept to power in the coup d’état of the 18th Brumaire, 1799. (The date is from the revolutionary calendar – “Brumaire” being the month of fog). While Napoleon Bonaparte had made bourgeois France into a great civic and military power (marching against the aristocratic regimes of Europe to free the peoples from feudal bondage and national oppression) the nephew was seen as an authoritarian but ineffectual leader who was to bring the country to the brink of ruin through corruption, patronage, military adventurism and where necessary the use of the lumpen proletariat to deal with his opponents.

The disastrous Franco-Prussian War of 1870 led to an inglorious setback and his abject surrender with the Prussian army at the gates of Paris. Marx had mocked Louis Napoleon by saying, “Hegel remarks somewhere that all great world-historical facts and personages appear, so to speak, twice. He forgot to add: the first time as tragedy, the second time as farce.” Marx’s Eighteenth Brumaire study of the bourgeois state in crisis, the stripping of liberal concessions and descent into police spies and military dictatorship, prototype of fascist and military coups of the 20thCentury, a device of last resort when bourgeois rule is threatened, is a masterly depiction of a state’s descent into rottenness.

It has remarkable bearing on South Africa today. Given telltale signs such as the growth of patronage, graft and corruption, misuse of public funds, attempts to undermine the media, public protector and judiciary, contempt for parliamentary opposition, allegations of conspiratorial plots, smearing of opponents, accusations of regime change, political assassinations, secret police surveillance, state violence against striking workers at Marikana and police brutality in response to civil protests etc etc, do we dare ask what circumstances could see the country slide into a regressive police state; martial law; treason trials; suspension of the Constitution and Parliament through a coup of sorts to save a rotten set of rulers who have been fleecing the state of billions? Some say, “Be afraid, be very afraid.” Others say “we are already afraid”. Yet others say: “Defend our democratic gains, expose corruption, mobilise a united front in defence of democracy, under the leadership of organised labour. A luta continua!” It raises the question of Marx’s comparison between Napoleon Bonaparte and his incompetent and corrupt successor: If Mandela is the eagle who then is the turkey?

The Paris Commune (1871)

Louis Napoleon’s rule started with the 18th Brumaire in 1851 and came to an inglorious end with his abject surrender to the Prussians after the short-lived war of 1870. In September 1870, Marx warned the French workers, artisans and small traders, armed and organised in the Parisian National Guard, in defence of their country against an untimely uprising. Paris was in the throes of the Prussian backlash, and faced the counter-attack of victorious Prussian troops camped outside the capital. The cowardly and treacherous French government and generals at the head of their troops had fled to Versailles, former seat of the deposed monarchy. It was from there that they secretly connived with the Prussian Chancellor Bismarck to help them destroy Paris’s armed republican citizenry. Not for the first or last time in history was a bourgeois government prepared to betray its own workers by plotting with the national enemy.

However, despite his reservations, when the uprising took place (March 1871), Marx enthusiastically hailed the revolutionary initiative of the masses, which were “storming heaven...’’ Denouncing such bravery was for him anathema. (Ref: Marx’s letter to Kugelmann). Marx’s nonsectarianism is worthy of note here, for this enthusiastic support was for an insurrection led by Proudhorn anarchists and Blanquists, with artisans, small traders and petty bourgeois radicals outnumbering proletarian fighters. After heroic endeavours they were brutally crushed with 25,000 Communards, women and children among them, mercilessly slaughtered. Double that number were imprisoned or exiled. A great opportunity had been lost when the Communards had allowed the bourgeois generals with their troops to escape to Versailles and prepare the counter-revolution unhindered.

A key lesson Marx drew from the fateful outcome was that, “The working class cannot simply lay hold of the ready-made State machinery, and wield it for its own purpose.” The state needed to be smashed and replaced. For the state is the instrument of the ultimate rule by force of one class over another. Violence by the state is the legalised monopoly of the ruling class. The Marikana miners were to learn this lesson in their 2012 strike and its bloody outcome.

Marx discerned a form of the “dictatorship of the proletariat” in the two months of the Paris Commune, in which sweeping changes in property relations and conditions of work were instituted along with the primary requirement of strengthening and arming the citizens National Guard in defence of the revolution. Among other measures was the payment of no more than a skilled workers’ wage to elected representatives of the National Assembly and public officials, together with the right of their immediate recall, full accountability, internal democracy and transparency to combat the rot of elitism and patronage. From that time onwards workers have constantly argued for such standards. This is proving to be a growing concern in South Africa. The term “Dictatorship of the Proletariat” has been used to convey a crackdown on rights and freedoms. In fact it is clear Marx was seeing a greater degree of democracy and accountability than had ever before existed in class based society, and was addressing the need for such a form of administration at a time of crisis. It is not about martial law or a justification of a one-party rule. A variety of parties were represented in the Commune.

Das Kapital

Marx’s study of political economy culminated in his greatest work, Das Kapital, researched and written over many years in London, which disclosed the laws of the capitalist mode of production, laid bare the hidden nature of surplus value and exploitation of labour power, and posited capitalism’s innate contradictions between the productive forces on the one hand and the fetters of its productive social relations on the other, which required to be “burst asunder” and ultimately replaced, through working class organisation and struggle, by socialism as the new mode of production and the stage towards a classless, communist society – “from each according to his/her ability to each according to their need”.

Without the material and moral support of Engels, who completed from Marx’s notes Volumes II and III of Capital after his death, the exhaustive work, which took its toll on Marx’s health, and the well-being of his family, could never have been written. We must not ignore the devoted support of his wife Jenny and the energy, charisma and labour of his disciple and youngest daughter Eleanor who was an organiser of the British and international working class and leading revolutionary feminist and assisted Engels in preserving Marx’s written legacy, papers and letters. (See Eleanor Marx, a biography by Rachel Holmes, Bloomsbury Publishers, 2014). Undoubtedly if she had been male she would have received far more notice in the revolutionary pantheon. We must never rest until women are fully emancipated, on equal terms with men, for the discrimination they face is of detriment to the working class, the trade unions, the struggle for socialism, and the health of society.

Marx’s accomplishment in Capital cannot be underestimated, especially when his theory of the crisis of over-accumulation – witnessed in the massive glut of over productive capital side by side with idle labour – is so much more compelling than the incompetent arguments of bourgeois economists. The latter believe markets equilibrate, that they move towards stability. It was one of Marx’s greatest contributions to political economy to prove the opposite: that the inherent crisis tendencies in the system lead to periodic ruptures. Class struggle is obviously part of this story, but it is only when class consciousness rises to the point that trade unions’ economist demands – and communities’ narrow material concerns – are augmented by a critique of the capitalist system, that a revolutionary situation can develop. Das Kapital is vital to that consciousness, because it separates the reformers from those who believe the laws of motion underlying the capitalist system “cannot be reformed, and must be overthrown”.

In the footsteps of Marx, his monumental labours and research, it is imperative that we continually analyse capital and wealth in our country; revealing where power really lies. The Gupta family might have an inordinate influence on President Zuma and company, and arrogantly flaunt their connections, but relative to controlling the commanding heights of the economy are miniscule compared to the really giant South African transnational Corporations like Anglo-American, Anglo-Vaal, Gencor, SANLAM, Rembrandt, ABSA. By comparison it is absurd to suggest the Guptas have “captured the state”. Look at those corporations and see who is quietly co-opting members of the emergent black political elite. The workings of modern capitalism are better studied by looking at how we as government allowed the likes of Anglo-America, Billiton, Old Mutual etc to avoid apartheid-era economic restitution, and through the lifting of exchange control were permitted to export huge sums of capital to list on the London Stock Exchange and incidentally beyond the reach of the quotas for Black Economic Empowerment.

Furthermore, as raised at the recent meeting for an alternative, independent trade union federation, “How do we explain that 22 years after the democratic breakthrough, mass unemployment, poverty, de-industrialisation, extreme inequality, racism and rampant corruption are the daily experience of the majority of the working class?” ( April 2016)

And what is happening to our environment and resources which demand vigilance, transparency and exposure by diligent research into the nature and workings of Capital. I posit but one example here of virtually secret and unknown uranium mining in the Karoo – said to be linked to the nuclear deal with Russia – which will dig a 70km trench between Beaufort West and Graff-Reinet to the detriment of farming, the poisoning of water resources and soil, creating uranium dust clouds and polluted water run-off for a century to come as far as coastal cities and towns and the degrading of the Karoo which is uniquely positioned for renewable solar and wind energy which could transform the region. This development has slipped by with scarcely any notice. (Ref: How nuclear power and uranium mining are undermining open government and communities a paper by Stefan Cramer on Face book: Stop Uranium Mining in the Karoo and M&G 15/04/16 article by Sipho Kings.)

Questions relating to the environment, climate, food security and water resources, sustainable development are very much class issues, which cannot be resolved by a nation in isolation, and are left to free market forces at our peril.

Legacy of Marx and Engels

Marx and Engels are universally recognised as the foremost revolutionaries of their and subsequent ages, whose teachings in theory and practise were brilliantly confirmed in their time. This confirmation moves through the 1848 and 1871 revolutions to the 1917 Russian Socialist Revolution, the rise of socialist and communist parties in every continent, the revolutions that followed after two world wars, from Europe to China, Vietnam and Cuba, and the national liberation struggles against colonial rule in Africa, Asia and Latin America.

While the young Marx’s earlier writings in the 1840s may suffer from insufficient awareness of conditions in Africa and Asia he was clearly making up for this in later life. One of the foremost and respected African-American scholars and activists, Dr W Du Bois was particularly impressed by Marx and became an influential Marxist and communist; as did the great African-American singer Paul Robeson and notably to this day Angela Davis.

Outstanding African revolutionaries such as Moses Kotane, JB Marks, Moses Mabhida, Yusuf Dadoo, Ruth First and Joe Slovo in our country became communists; as did the younger generation of Chris Hani and Thabo Mbeki. Leading revolutionaries in Africa such as Amilcar Cabral, Agostinho Neto and Samora Machel were attracted to Marxism. From Asia we simply need to add the names of Ho Chi Minh, General Vo Nguyan Giap, Mao Zedong, and Chou En Lai and from Latin America Fidel Castro and Che Guevara. Such names of great men and women represent hundreds of millions of human beings inspired by Marxism. Such is the testament to Karl Marx’s universal relevance and appeal.

Conclusion

Whatever the setbacks resulting from the counter-revolutions launched by feudal monarchies and bourgeois regimes in the contestations of Europe’s 19th century revolutions in which Marx and Engels participated or in the 20th century’s dramatic conflicts the Marxist legacy lasts to this day – despite repeated attempts to write its obituary and declare the end of history. In fact there is an international upsurge of interest in the writings of Karl Marx.

To those who claim that the demise of large scale industrial production in many developed countries is the obverse of Marx’s expectations we may observe that the relocation of industry to countries where labour is cheap and non-unionised does not negate Marx but in fact proves his salient points about the class struggle and the law of capital seeking the greatest degree of profit and a docile labour force.

However, as the Communist Manifesto pointed out, capital grows the proletariat as it develops the instruments of labour and industrialises. This new work force of proletarians might be relatively passive at first but they will learn to combine in their own interests and become militant as class consciousness is formed. The number of workers might well decrease in some countries but they multiply in others across the globe. Just think China and India, Nigeria and Brazil. The fact that workers of advanced capitalist countries have much more to lose than their chains is owing not to the magnanimity of capitalists but to the class struggle which won for labour the right to form trade unions, the right to strike, the eight hour day, better conditions of work, decent housing and so on. All these advances are today under the threat from the capitalist bosses facing crises and perfectly in keeping with how Marx understood the laws of capital.

Marx died on March 14th, 1883. Marxism, unlike religious belief, is not cast in stone. It needs to be enriched with new propositions and conclusions, keeping pace with changing conditions. This is the challenge every would-be revolutionary movement is faced with.

In a world mired in capitalist crises, in which the ownership of the means of production becomes concentrated into fewer hands (the one percent owning the lion’s share of all wealth), with the gap between rich and poor increasing exponentially and obscenely, with international monopoly capitalism and its free market economics creating wastelands, mass unemployment, starvation amidst the perennial crises of overproduction where goods, land and industry is laid waste, where pursuit of profit devastates the planet, destroys the environment affecting climate change and food security, plunges the world into wars with nuclear arsenals capable of the destruction of all life, humanity has a profound weapon, more powerful than imperialism’s weapons of mass destruction and that is Marxism – a compass for the labouring masses, vital for the strategic and tactical route to socialism, vital for Africa and our country; as relevant and necessary as ever.

What is essential today is an international solidarity movement uniting the broad masses of people of all lands under the leadership of organised labour, of hand and brain, to stop in their tracks the perfidious transnational corporations, their government tools, and capitalism’s imperialist wars – towards a new internationalism of the working class, labour masses, and freedom loving people everywhere.

[Ronnie Kasrils was South Africa's Minister for Intelligence Services from April 2004 to September 2008. He was a member of the National Executive Committee (NEC) of the African National Congress (ANC) from 1987 to 2007 as well as a member of the Central Committee of the South African Communist Party (SACP) from December 1986 to 2007.]

Spread the word