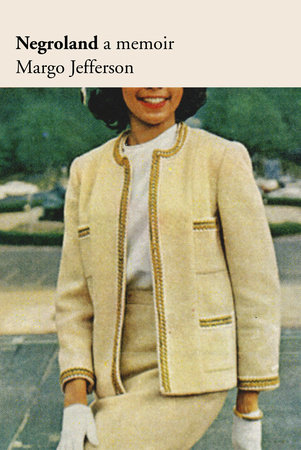

Negroland in its heyday, from the 1940s through the 1960s, was an extraordinary place to live. Its families enjoyed privilege, wealth, and opportunity beyond that experienced in other parts of black America: its citizens were doctors; lawyers; academics; scientists; publishers; a few well-placed clergymen (women were not yet ordained); highly successful artists and entertainers; champion athletes, if they had enough money to make up for a lack of education; and a few moguls and tycoons. Together they enjoyed the fruits of their hard work and good fortune. The national motto: “Achievement. Invulnerability. Comportment.”

It was, like most countries, an abstraction: a locus of shared history, complex loyalties, and distinctive rituals and mores; controlled by ruling hierarchies, it was sometimes roiled by internecine tensions. But it was also a physical, geographical reality: latitude and longitude placed it above the equator, part of the continent of North America, with borders often indicated by the red lines on the real estate maps of major American cities. Travel across borders could be subject to restriction and risk. Throughout the twentieth century, all regions of black America stood in stark contrast to, and deeply justified distrust of, white America. Negroland, though, stood apart from both white America and most of black America. It was an archipelago of the looming, white mainland and dependent upon it for survival.

Margo Jefferson was raised in this environment to be “wholly normal and wholly exceptional.” She belonged to a small subset of midcentury African American children who were raised in a rarified hothouse intended to produce blazingly overachieving men and women—vindicating previous generations of black American suffering, humiliation, pain, and rage.

Jefferson declares herself “a chronicler of Negroland, a participant-observer, an elegist, dissenter and admirer; sometime expatriate, ongoing interlocutor.” She begins her memoir with a brisk flyover of its historic beginnings. She touches on its slave origins and its rich history of personal, communal, and cultural achievement. She moves from a sharp focus on the lives and achievements of specific individuals and families, to the broad vistas of the Civil War and Reconstruction, to the various migrations northward that led to the founding of Negroland. This introductory section is a tour de force of the incisive, eloquent, and elegant writing that shapes this work from its historically informative beginning to its startling conclusion.

Jefferson is a Pulitzer Prize-winning cultural critic and journalist. During her decades at the New York Times, she was celebrated for her heart-of-the-matter assessments of the work of the day’s most original and influential artists, entertainers, and intellectual heavy-hitters. That meant locating herself as an attentive ear and reactive voice to the call-and-response of the American cultural zeitgeist, while offering insights and analyses that would move the conversation forward. But as a black woman writing for the United States’ “newspaper of record,” whose culture was she addressing? Whose zeitgeist? Was it her own, although she seldom saw herself reflected in its manifestations? Or, seeing the denizens of Negro America and of Negroland caricatured and stereotyped—either deliberately or inadvertently— did she ask herself if it was better to be ignored than to be humiliated?

Jefferson, the author of a book called On Michael Jackson (2006), was in her professional life a liminal figure, thoroughly conversant with two worlds often at odds with each other. Her stock in trade was the explication of each, although not necessarily one to the other. She was among those who paved the way for the current moment of expanding opportunity and achievement for black women in national media. But it’s clear that those paving stones could become pretty Sisyphean when the work included an element of assault against the barricades. As, for example, in one of a group of dialogues Jefferson posits on race and gender:

-The women of our generation weren’t well trained in the narratives of the male workplace

-We’re learning. I’ve just been in a pissing contest with an associate.

-Did you win?

-I will. Now I know it doesn’t have to be bigger, it just has to piss farther.

Jefferson’s father was a physician, chair of the department of pediatrics at Provident, the nation’s oldest black hospital. Her mother had studied social work and practiced for a few years, but gave up her career to raise Margo and her older sister, Denise, “to become a full-time wife, mother, and socialite.” The Jeffersons married during World War II and were among the founding families of Chicago’s Negroland, which was both a conglomeration of sometimes shifting neighborhoods and a well-defined social milieu. Those not born to the black elite could marry into Negroland, or vault in over the ramparts by virtue of outstanding achievement, but the distinction between them and hereditary members of this world never disappeared completely.

The Jefferson sisters grew up in a charmed environment with ballet, piano, and violin lessons, private summer camps, family vacation enclaves, a family boat, and a host of organizations that provided a peculiar kind of buffer between their world and the white world beyond. “In Negroland,” Jefferson writes, “we thought of ourselves as the Third Race, poised between the masses of Negroes and all classes of Caucasians.” There were young people’s clubs that offered membership only to children from the right sorts of families. There were the men’s clubs, women’s clubs, fraternities, and sororities that echoed their exclusive and expensive all-white counterparts. For the daughters of Negroland, much depended upon manners, background, poise, and proper speech—things one could either be born into or taught. But much also depended on shades of skin color, hair texture, the size and shape of a nose, the tenor of a voice, and other involuntary grounds for cruel or merely capricious exclusion.

For a sensitive, bookish young girl, such a world was both carapace and chrysalis. While there was certainly no shortage of parental love, devotion, care, and sacrifice, the children of Negroland were explicitly handed the burden of being generational point persons for assaults on the institutions of the dominant culture. First the schools, then the professions; they were expected to become pioneers, groundbreakers, ceiling smashers. But at what psychological cost? Once launched into the worlds of higher education and work, there was always the ambush of repeated outrages, great and small. The stories traded back and forth of being taken for an underling—for the waiter at an exclusive dinner, the secretary at the law firm, the orderly at the hospital, never mind the stethoscope around your neck. And these were followed by the delicate exercise of explaining oneself without demeaning the people who held those service jobs—all the while contending with ominous exhortations from a few rungs down the social ladder not to “forget where you came from.” As if.

School was an additional crucible, to which Jefferson gives sharp and probing attention. The one Jefferson and her sister attended (and all right, all right, I, too, for a while, before my family moved East—as if you didn’t suspect as much) was called a Laboratory. Not that it was designed for us—but for high achieving or aspiring black families of that era and in that city, the University of Chicago Laboratory Schools, nursery through high school, where at least half of the students were the children of university faculty or staff, were the prized enrollment for their children. Founded in the nineteenth century by John Dewey, the schools did not admit their first black students until the 1940s; those of my generation were their newest guinea pigs. And as I read, it was startling and bittersweet to come upon the names of childhood friends, some deceased, some long since out of touch, some few still, or again, in my life. For Jefferson, the Lab Schools were the sites of most of her academic, social, and wider white-world education beyond Negroland. Her path home from school was across the Midway, the huge, blocks-long grassy expanse originally constructed as part of the 1893 Columbian Exposition, an extension of the White City at its heart. “So we, Lab’s Negroes, would leave the White City of Lab, cross the Midway, and take one or, usually, two buses” to homes in the better Negro neighborhoods, writes Jefferson.

Negroland is a book of raw elements with no chapter headings. It includes segments of various lengths, cinematic narrative jump cuts, dispassionate third-person observation, and urgent first-person testimony—the latter never more so than in the breathtaking section that begins “In Negroland boys learned early how to die.” It was one thing to strive to be a “Good Negro Girl,” following your marching orders of duty, obligation, and discipline. If you found yourself, years later, out in a world with too few external points of reference or aspiration beyond an unwelcoming white society, there were the options of the therapist’s office and the psychopharmacologist’s potions. But what of the sons? Turning away from the approving mirror of family and social circle, they walked into the institutions of a larger society that did not wish them well. And yet, it was the one in which they were conditioned, indeed condemned and trained, to compete—to both emulate and best the enemy. So many young men coming of age in Negroland in those days had to cobble together inner resources of the spirit. After all, hadn’t their fathers done it? But this was not the world of their fathers, and many died trying.

Humor is one among the necessary things that carries us through. All of us, of whatever origin. Margo Jefferson is candid, wry—mocking and self-mocking. Hers is wit that sees both the absurdity and the pathos in a line that she ruefully quotes a few times, from a letter her mother wrote to her father, when they were separated during the war: “Sometimes I almost forget I’m a Negro.”

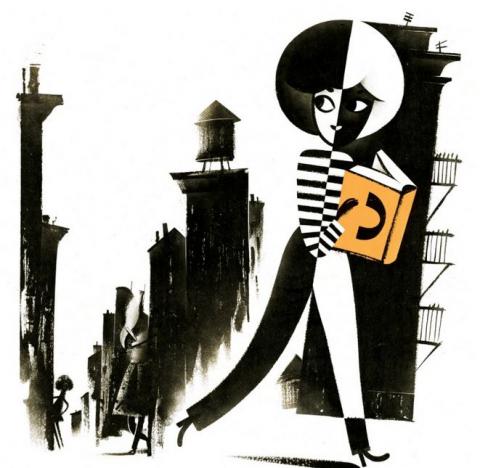

Blackness is not an issue for Christine Clark, a.k.a., Oreo. It is just part of who she is. As is her Jewishness, although less obviously so. Both Jefferson and the fictitious Oreo honor the ancestors, though. Each would recognize the other’s central question “Who are your people?” For Oreo, the answers begin in black Philadelphia, lead her to New York City, and conclude in Theseus’s Minoan labyrinth. Author Fran Ross starts out with a disclaimer as part of Oreo’s epigraph—“Oreo, ce n’est pas moi”—attributed to “FDR.” Fran Deloris Ross, that is. So never mind that the brilliant, hilarious, multilingual, brash, tender, bawdy, and unsentimental voice of Ross’s heroine equals the rare and outrageous voice of Ross herself, a woman hired, after all, to write for Richard Pryor. When his show was canceled, Ross went from Los Angeles back to New York, where she continued to work as a writer and editor. This book is the result. It did not fly off the bookstore shelves when it first came out in 1974. Fortunately, it’s back, for the reading pleasure of those who revel in laugh-out-loud-in-public books with kick-ass heroines and brilliant, abundant plot lines. Sadly, it is unique. Ross died in 1985. But what a legacy! Oreo is a Joycean hero’s journey. A black girl’s manifesto. A family saga that searches down the generations all the way back to Greek myths. Ross is a writing whirlwind. This, from a reverie on a woman determined to become a football player (!): “Imagine what astrodomes of nature and nurture she had to friedan in order to test that artificial turf.” Or this, at the conclusion of a conversation with a man determined to pave over Central Park: “‘Remember, he said as she was leaving, ‘look out for rock outcroppings. Manhattan is full of schist.’”

“And so are you, thought Oreo, misunderstanding him.”

Oreo is raised from a young age by her grandmother Louise, a formidable woman with “a love-tap on her that could paralyze yeast for three days.” Louise speaks in the worst kind of down-home dialect: Christine was actually nicknamed for a bird that had appeared to Louise in a dream—an oriole—although there was some confusion about it between Louise and the neighbors, who heard the name differently. Louise is a remarkable cook. Here’s a selection from the menu for the homecoming dinner she makes for Helen, Oreo’s mother, who is a traveling musician and mathematician:

La Carte du Dîner D’Héléne

halibut imojo

CHEESE AND CRACKERS

Leberknödel

dim sum

pâté maison

funghi marinati

PICKLED HERRING

sashimi

empanadas

vatrushki

Zubrowka

Aquavit

Pepsi…

Etcetera.

Music compels Helen’s son as well, Oreo’s brother Moishe. Called Jimmie C, he speaks and sings in a language of his own invention that sounds very much like bebop scat singing. In fact, Oreo is the first (only?) American klezmer novel, a fine literary mashup of raucous jazz and equally raucous Eastern European Jewish celebratory music. Neither tradition is a stranger to songs in a minor key.

Oreo, in preparation for her journey to follow the clues and solve the riddles that will enable her to discover her origins, adopts the ancient motto, “Nemo me impune lacessit”—“No one attacks me with impunity.” She explains, “Ain’t no nigger gon tell me what to do. I’ll give him such a klop in the kishkas.” (This is a book written before the word “nigger” was sanitized into “the n-word.”) She also develops a system of martial arts, the Way of the Interstitial Thrust, or WIT, described in some detail and used to excellent effect against a sadistic pimp. The virginal Oreo goes into battle wearing a mezuzah, sandals, a bra—and an invincible secret weapon up something other than her nonexistent sleeve.

Jefferson describes, with admiration verging upon awe, the late Florynce Kennedy, the first black feminist she had ever seen “in public and in action.” With a “whiplash tongue and a cowboy hat….dangling earrings and many necklaces,” Kennedy was a woman who had “planted herself and thrived in every movement that counted: civil rights, antiwar, black power, feminism, gay rights. Her principles never swerved; her tactics never staled,” Jefferson writes. Ross and Jefferson are both after a Flo Kennedy-esque wit that incorporates style, command, and personal freedom: the enduring and empowering wit that is the wellspring of women’s survival is at the beating heart of each of these books.

Both Negroland and Oreo have complex conclusions. Jefferson and the fictitious Oreo prevail. They grow in grace and wisdom. But both Jefferson and Ross are better people, and better writers, than to offer their readers a ready conclusion, or even to suppose there is such a thing. As Jefferson writes, “Being an Other, in America, teaches you to imagine what can’t imagine you.” There is no way to write finis to that.

[Marilyn Richardson writes about intersections of art and history.]

Information on Women's Review of Books is available here.

Spread the word