Doing so, they argue, will pave the way for a “transformative crisis,” much like the crisis of the Whig Party in the 1850s, from which a new, working class party can emerge.

It may be a hard sell to convince contemporary readers that the collapse of the Whigs and the birth of the Republicans in the 1850s is relevant to today’s partisan flux. Nonetheless, Fletcher and Davidson invoked this precedent and we should take it seriously. Examining the only prior process of party decomposition leading to ideological realignment in U.S. history will clarify the depth of the challenges facing us, and some of the opportunities as well.

The U.S. Party System

Before tracing the similarities and differences between the 1850s and today, a few introductory remarks are in order about the U.S. party system itself and in the period leading up to the crisis of the 1850s.

First, I want to emphasize my agreement with Fletcher and Davidson’s point that the Democratic Party—like all U.S. political parties—is not a political party in the usual sense, but rather a floating coalition or vehicle. I will add one point.

What distinguishes the U.S.’s vaunted “two-party system” is that both of the party formations are really parastatal apparatuses, in that they exert exclusive legal control over access to the ballot. In other words, they determine for whom you can vote. This restriction forces all kinds of partisans, from far right to radical left, into one or the other if they want to have any access to the state.

Go to other electoral democracies, and you will find multiple parties putting up lists of candidates, often a dozen or more, because ballot access is open. Inside the U.S., we can see what vigorous multi-party competition looks like via the political history of New York state. Many activists know that because of the legality of “fusion” tickets, the Empire State has featured many so-called “third parties” in its recent history, including the American Labor, Liberal, Right to Life, and Conservative parties and (most recently) the Working Families Party. This is nothing new. In the 1850s, for instance, voters were presented with up to seven statewide tickets, including three different varieties of Democrats.

Second, it’s worth giving a brief pre-history of U.S. political parties leading up to the period of party disintegration and formation that takes place in the 1850s.

There were two long-lasting “party systems” before the Civil War. In the 1790s, the revolutionaries divided into Alexander Hamilton’s Federalists and Thomas Jefferson’s Republicans. Federalists were ardent nationalists, favoring a strong state, and in some senses progressive. Most free black men and early abolitionists favored them. Jeffersonian Republicans put states’ rights and the prerogatives of the South first, but they drew support from northerners who saw Federalists as pro-British aristocrats. From 1800 to 1824, Southern Republicans dominated national politics via three Virginian presidents: Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, and James Monroe. The Federalists faded away while becoming increasingly anti-Southern and anti-slavery. By the 1820s, virtually everyone claimed to be a Republican. The main divisions were “sectional,” meaning North versus South.

The Second Party System emerged in 1828 as these ideological trends took new organizational forms. President John Quincy Adams ran as a “National Republican” avowing much of the old Federalist program. He was opposed by Andrew Jackson, whose new Democratic Party (also called “the Democracy”) advocated the republicanism of Jefferson, especially in its laissez-faire, states’ rights, herrenvolk (master race) dimensions. Jackson won resoundingly, and his Democratic Party became the most powerful political force for a generation, winning six of eight presidential races in 1828-1856.

In the 1830s, National Republicans coalesced with other reform-oriented groups to form the nationalist (as in statist), development-oriented Whig Party, whose chief leader was Henry Clay, a moderate Upper South slaveholder. As strange as it may seem, most anti-slavery politicians and free men of color in the North were Whigs, in many cases even into the 1850s. Like the Democrats of today, Whigs were united in their opposition to what they saw as a reactionary party but, also like today’s Democrats, antislavery Whigs were deeply compromised by their partisan alliance. By the 1850s, the parties entered into a period of transformative crisis.

What can we learn from the party realignment of the 1850s?

Several discrete historical comparisons will serve to aid strategic thinking about a left electoral strategy.

1. Party decomposition tends to spread from one party to another, leading to a period of extreme flux, where party fractions move around, coalescing and breaking apart at every level.

To focus only on the Whigs’ rapid disintegration after their defeat in 1852 misses one half of the process of realignment. Despite convincing national wins in 1852 and 1856, the Democrats—following the emergence of the Republicans as a powerful “Northern party” in the latter year—split into bitterly antagonistic northern and southern wings, driven by the southern Democrats’ insistence on controlling the national ticket and program so as to guard the slave system. In 1860, they ran opposing candidates (Stephen A. Douglas in the North and John C. Breckinridge in the South) and split the Democratic vote. This division was the basis of Abraham Lincoln’s Electoral College victory on the Republican ballot line with only forty percent of the popular vote, helped by the fact that the “Old” Whigs ran a Constitutional Union ticket, which got only thirteen percent of the vote but carried three Upper South states.

Do not think such a divide is unimaginable today, when the Republican Party has also been “southernized” and Trumpified. We need to anticipate that version of realignment, because the emergence of a moderate, non-southern ticket led by someone like Michael Bloomberg or Howard Schultz would be powerfully seductive to corporate-Clintonian Democrats.

2. Another possible precedent is the sudden emergence of short-term wild cards.

Parties of this type take shape when voters, feeling unmoored from their historic affiliations, park their anxieties in new party formations or candidates. Think, for example, of French President Emmanuel Macron’s La République En Marche or Ross Perot’s candidacies in the 1990s, first as an independent and then on a newly-minted Reform Party ballot-line. These wild-card formations add to the extreme uncertainty of a schismatic period. The most relevant example from U.S. history happened during the antebellum decades, after the War of 1812 and before the Civil War, when fear of Catholic immigrants acted as a solvent for the national-patriotic unity otherwise slipping away. Local and state nativist tickets periodically surged in the 1840s, and briefly, in 1854-1856, when the Know-Nothing “American” Party seemed poised for power after winning several governorships and control of state houses and city halls. In 1856, they ran ex-President Millard Fillmore, a former Whig. He got twenty-one percent of the vote, but the Know-Nothing Americans were already collapsing because their northern and southern wings could not avoid the issue of slavery.

What or who would act as a stand-in today is anyone’s guess, but it’s a distinct possibility.

3. A realignment will not happen over one or two elections.

The Republican Party that suddenly emerged across the North in 1854 had ample precedents. Its roots lay in the abolitionist Liberty Party’s emergence in 1840 as a left-wing split from the Whigs. The “Liberty men,” as they were called, had a major electoral impact over the next six years in New England, New York, and parts of the Midwest by forcing Whigs and Democrats to define themselves as for or against slavery. In 1848, most of them joined radicalized “Conscience Whigs” and a faction of anti-southern Democrats to form the Free Soil Party, committed to keeping slavery out of the vast western territories. Running ex-president Martin Van Buren as their candidate, the Free Soilers won ten percent nationally, and came in second in Massachusetts, Vermont, and New York. Despite this auspicious debut, they never broke through after that to major-party status.

The lesson here is that it is extremely difficult to break up an existing party. Even the most committed anti-slavery Whigs—men like William Seward, John Quincy Adams, and Joshua Giddings—maintained a commitment to their national organization even if it meant “fellowshipping” (collaborating with) slaveholders. The same has been true of left-wing Democrats since the 1970s. The party of Jesse Jackson, Bella Abzug, and Ronald Dellums was also the party of Bill Clinton, Jim Wright, and Al Gore. It took an extraordinary series of defeats to break up the Whigs. We will need equivalent shocks to reorient the Democratic Party to the left or create an essentially new party under whatever name.

4. Most significant is what we are missing now, versus then.

The challenge for the left if it follows the path laid out by Davidson and Fletcher will be to build a new party inside the husk of the old, without the benefit of much practice. We have no forerunners equivalent to the Liberty and Free Soil formations. The New, Green, and Labor Party efforts of the 1990s and 2000s have only minor relevance to the current surge of left-wing electoralism. If they did, Bernie Sanders and the flock of DSA candidates would have emerged from their frame, instead of suddenly appearing circa 2016. Only New York’s Working Families Party forms a kernel of experience upon which we can draw.

This lack of electoral skills and seasoning on the left is just the beginning. The Republican Party was remarkably effective post-1856 because it inherited a cadre of sophisticated political strategists who led functioning local and state apparatuses. Most notable was the powerful machine run by William Seward, Thurlow Weed, and Horace Greeley in New York, then by far the most populous state. The ultimate Radical, Thaddeus Stevens, was the White South’s devil figure well into the twentieth century (even appearing as the evil genius in Birth of a Nation) precisely because he was a brutally skillful parliamentary infighter. To suggest that no group in or around the Democratic Party left measures up to that standard severely understates the problem. Back then, most counties had a widely-read party organ bristling with national political news, a network of volunteers skilled at turning out their vote, and full use of the patronage to succor the faithful.

With some exceptions, today’s parties are hollow, residual structures. This is exemplified by how many congressional seats the Democrats do not contest and the abysmal turn-out in local elections. And, as Jon Liss and other members of the State Power Caucus have estimated, left grassroots organizations are currently only able, at their peak, to mobilize roughly four million people. Before even beginning to organize, serious party builders would need to commission a survey of counties to trace where, to what extent, and by whom this “party” is actually maintained, instead of relying on anecdotal evidence and untested assumptions.

5. Another basic difference between then and now is that today whole groups of voters, donors, and office-holders act autonomously within the Democratic Party—Blacks, Latinos, and Jews, most obviously.

There is no equivalent in the antebellum decades, except perhaps the Irish, who were so completely incorporated into the Democratic Party as to be irrelevant to our comparison. The only possible parallel is the newly-arrived German-Americans. In the 1850s, every Republican strategist knew they needed the German vote, and they did what they had to do to get it: repudiating nativism, actively soliciting candidates (Carl Schurz is the best-known today), and publishing slews of campaign materials in German. It worked.

Still, this example is hardly the same as today’s ethnic free-for-all, wherein legitimacy grounded in representative politics is a central partisan dynamic. It is unrealistic to imagine ethno-racial politics will (or should) go away in a realigned SocialDemocratic party. It would be in the left’s long-term interest, however, if the Republicans stopped being the white nativist party, and moved in the direction envisaged by George W. Bush and his handlers, incorporating fractions of Latinos, Asians, and even African Americans of the Tim Scott variety into a Party of Business, small and large. Neutralizing race-only politics would be a step forward, if highly unlikely in a polity where the desperate effort to maintain white supremacy remains the main dynamic on the right. The GOP would be a better foe as a party explicitly organized on class rather than racial terms—easier to beat, anyway. Instead, as the Trump Party, they drive millions of center-right voters towards the Democrats, which severely complicates efforts to make the Democracy (as it was called back then) a party of the multiracial left.

6. Here is one way the current crisis strongly resembles the 1850s: conventional centrists are producing startlingly radical proposals, to keep up with their party’s base.

Democratic candidates at every level are now competing on the left for the first time since the 1968-1974 period, when liberalism got radicalized by the Vietnam War and other rapid-fire developments. In the final prewar decade of the 1850s, as the Whig Party collapsed, many one-time moderates spoke out sharply on how slavery was antithetical to republican values, and the danger of the “Slave Power” dominating the nation. Lincoln, an obscure former congressman, was one of hundreds of Whigs who moved left as they broke free from a national party tied to its southern wing.

Sorting out who was an opportunist was difficult, then and now. In both cases, it was the party’s grassroots that moved. The politicians either followed or were rapidly marginalized, like the many “Old Line” Whigs relegated to obscurity. One hopes a similar fate awaits the Blue Dogs and “New” Democrats! We cannot equate today’s urgency over income inequality, the carceral state, reproductive justice, and Trump with the overwhelming force of anti-slavery in Northern politics after 1854, but the parallel is still valid.

Obviously, the danger of opportunism is real. In 1856-1860, Republican leaders looked all over the North for candidates not linked to abolitionist “fanaticism.” In 1856, they nominated California Senator John C. Fremont precisely because he did not have much of a record and was a military hero. Leading up to 1860, Lincoln positioned himself as the consensus candidate because he was not William Seward (formerly New York’s Governor, now its senior Senator) or Ohio Governor Salmon P. Chase, both powerful state leaders associated with anti-slavery politics and advocacy of the rights of free people of color, including equal suffrage for black men. Lincoln, by contrast, had no connections to abolitionism and did not know any black leaders. Fortunately, he proved to be a figure of republican principle. Or, to put it another way, he recognized what his party stood for and maintained its discipline under great pressure once southern states began seceding in late 1860.

7. A final parallel is that formerly marginalized radicals suddenly acquire moral legitimacy, while movement activists move into party structures.

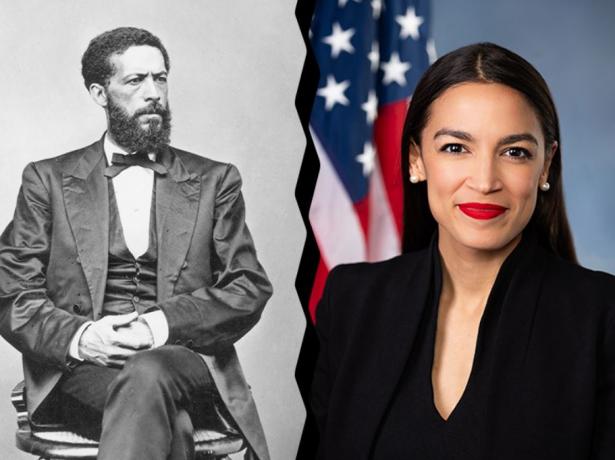

Here the comparison is obvious. Bernie Sanders is now a major Democratic leader just as Chase, who had built Ohio’s Liberty Party into a balance of power and engineered the Free Soil alliance, became the leading Republican in the nation’s third-largest state. But this trend transcends a few famous individuals. By the late 1850s, the state legislatures and congressional delegations across much of the North included former Liberty men and well-known stationmasters on the Underground Railroad. They are the equivalent of Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, Ro Khanna, Rashida Tlaib, and the dozens of others winning office as Democrats at every level, radicals operating within the electoral system much like the Radical Republicans before and during the war, who were determined to save the republic by destroying slavery.

Are we the new Radical Republicans?

In its brief, radical heyday, the Republican Party was the one truly revolutionary political party this country has ever seen. It smashed an entire mode of production through military force and a massive expropriation of capital, briefly turning the freedmen into citizens and voters, before retreating in the face of armed counter-revolution.

We have the same enemy now: a politics of white supremacy undergirding racial capitalism, with its power concentrated in the South. Do we have the political will to converge with the same force as the Republicans did? Will the “unfinished revolution” of Radical Reconstruction at long last be completed?

Time will tell.

For those who are interested in reading more, Prof. Van Gosse has provided the following bibliography of relevant books detailing this period.

Douglas Bradburn, The Citizenship Revolution: Politics & the Creation of the American Union, 1774-1804 (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2009)

Padraig Riley, Slavery and the Democratic Conscience: Political Life in Jeffersonian America (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2016)

David Hackett Fischer, The Revolution of American Conservatism: The Federalist Party in the Era of Jeffersonian Democracy (New York: Harper & Row, 1965)

Leonard L. Richards, The Life and Times of Congressman John Quincy Adams (New York: Oxford University Press, 1986)

William Lee Miller, Arguing Over Slavery: John Quincy Adams and the Great Battle Over Slavery in the United States Congress (New York: Vintage, 1998)

James Brewer Stewart, Joshua R. Giddings and the Tactics of Radical Politics (Cleveland: Case Western Reserve University Press, 1970)

Daniel Walker Howe, The Political Culture of the American Whigs (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1979)

Howe, What Hath God Wrought: The Transformation of America, 1815-1848 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007)

James Brewer Stewart, “Modernizing `Difference’: The Political Meanings of Color in the Free States, 1776-1840,” Journal of the Early Republic (Winter 1999)

Lee Benson, The Concept of Jacksonian Democracy: New York as a Test Case (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1961)

Corey M. Brooks, Liberty Power: Antislavery Third Parties and the Transformation of American Politics (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2016)

Tyler G. Anbinder, Nativism & Slavery: The Northern Know Nothings and the Politics of the 1850s (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994)

William Cheek and Aimee Lee Cheek, John Mercer Langston and the Fight for Black Freedom, 1829-1865 (Urbana: University of Illinois, 1989)

Phyllis F. Fields, The Politics Of Race In New York: The Struggle For Black Suffrage In The Civil War Era (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1982)

Robert J. Cottrol, The Afro-Yankees: Providence’s Black Community in the Antebellum Era (Westport, CT: Greenwood, 1982)

Eric Foner, Free Soil, Free Labor, Free Men: The Ideology of the Republican Party Before the Civil War (New York: Oxford University Press, 1995)

Eric Foner, The Fiery Trial: Abraham Lincoln and American Slavery (New York: W.W. Norton, 2011)

Eric Foner, Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution, 1863-1877 (New York: Harper Perennial, 2014)

James Oakes, The Scorpion’s Sting: Antislavery and the Coming of the Civil War (New York: W.W. Norton, 2014)

[Van Gosse is a Professor of History at Franklin & Marshall. After writing about the New Left “movement of movements” for some years, he now studies black politics between the Revolution and the Civil War. He has been active in peace and solidarity work since the 1980s (CISPES, Peace Action, United for Peace and Justice) and helped found Historians Against the War, now H-PAD, in 2003.]

Spread the word