Noel Ignatiev, a former steelworker who became a historian known for his work on race and class and his call to abolish “whiteness,” died at Banner-University Medical Center Tucson on Saturday. He was 78. The cause was an intestinal infarction, according to Kingsley Clarke, a longtime friend.

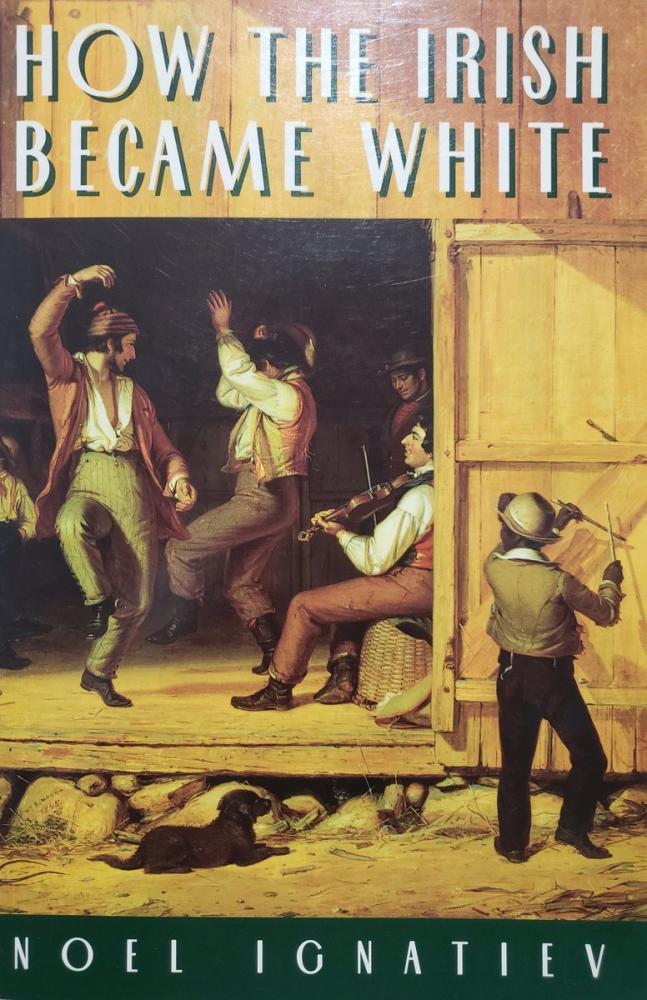

Ignatiev’s best-known book, “How the Irish Became White,” was immediately influential and controversial upon its publication in 1995. It touched off a firestorm of debate at the time at academic conferences and in the pages of newspapers. In time his view that whiteness is a social and political construction — and not a phenomenon with a biological basis — has become mainstream. The resurgence of white identity politics and white nationalism in recent years made Ignatiev’s arguments relevant to a new generation of readers who argued the notion that race is more about power and privilege rather than about ancestry, or even identity.

The book detailed how the Irish, who had first come to North America as indentured servants and were reviled by the more settled populations of English and Dutch Americans, became, by the mid-19th century, accepted as white. Sadly, Ignatiev argued, the Irish became incorporated into whiteness just before the Civil War, through support for slavery and violence against free African Americans. To become white, Ignatiev wrote, did not mean to be middle class, much less rich, but rather to be accepted as equal citizens and to have access to the same neighborhoods, schools and jobs as others.

“To Irish laborers, to become white meant at first that they could sell themselves piecemeal instead of being sold for life, and later that they could compete for jobs in all spheres instead of being confined to certain work; to Irish entrepreneurs, it meant that they could function outside of a segregated market,” Ignatiev wrote.

“To both of these groups it meant that they were citizens of a democratic republic, with the right to elect and be elected, to be tried by a jury of their peers, to live wherever they could afford, and to spend, without racially imposed restrictions, whatever money they managed to acquire. In becoming white, the Irish ceased to be Green.”

Ignatiev’s argument touched off fierce debates; critics argued that he went too far in conflating racial and class privilege. He went on to found and co-edit a journal, known as Race Traitor, whose motto was “Treason to whiteness is loyalty to humanity.” His ideas seemed extreme for the time; critics called Ignatiev — who was Jewish — divisive, even self-hating.

At a 1997 conference at UC Berkeley, on “The Making and Unmaking of Whiteness,” Ignatiev argued that “whiteness is not a culture but a privilege and exists for no reason other than to defend it.”

“You’re white,” a New York Times interviewer asked Ignatiev in 1997. “Do you hate your own hide?”

Ignatiev replied; “No, but I want to abolish the privileges of the white skin. The white race is like a private club based on one huge assumption: that all those who look white are, whatever their complaints or reservations, fundamentally loyal to the race. We want to dissolve the club, to explode it.”

Ignatiev urged white people: “Be reverse Oreos. Defy the rules of whiteness — flagrantly, publicly. When someone makes a racial slur in your presence, say, ‘You probably think I’m white because I look white.’ Challenge behaviors that reproduce race distinctions.”

The interviewer continued: “You’d do this in a bar full of rednecks?”

Ignatiev replied: “That depends a lot on the situation. Challenging people on their whiteness can lead to harsh confrontations, even blows. Sometimes that can’t be helped. But since we don’t accept labeling people, I’d ask you: What’s a redneck?”

Heavily influenced by Marxism, Ignatiev said the journal’s purpose was to chronicle and analyze the making, remaking and unmaking of whiteness. “My book on the Irish was the story of how people for whom whiteness had no meaning learned its rules and adapted their behavior to take advantage of them,” he told Harvard Magazine. “Race Traitor was an attempt to run the film backwards, to explore how people who had been brought up as white might become unwhite.”

Ignatiev’s ideas have continued to be controversial, particularly as race has returned to the center of American politics.

Writing in the Washington Post in 2017 to lament the rise in “whiteness studies,” David E. Bernstein, a conservative law professor at George Mason University, called Ignatiev’s ideas “interesting” but argued that Irish, Italians, Jews and other ethnic groups were “indeed considered white by law and by custom.”

Bernstein added: “The racist pseudo-science of the day divided Europeans into various races by nationality or perceived nationality, and often created a hierarchy among those groups. But that was a racist hierarchy within the white group, not evidence that these groups weren’t considered to be white.”

Adam Sabra, a historian at UC Santa Barbara, who was close to Ignatiev, cited his contributions to history. “Noel Ignatiev was an encyclopedia of the American left as it developed since the 1950s,” Sabra told The Times. “In losing him we lost an essential voice. In particular, his scholarship on whiteness as a social category and his activism that aimed at eliminating it were crucial interventions in American political life.”

Born Dec. 27, 1940, Ignatiev was a child of working-class Russian Jewish immigrants. He grew up in segregated Philadelphia, where he was often the only white patron at the free community pool; his parents had refused to pay a $1 fee that was designed to keep other public pools all white.

After dropping out of the University of Pennsylvania in 1961, Ignatiev worked in a Chicago steel mill and then made farm equipment and machine tools. At the mill, he helped organize strikes and protests by the workers, who were predominantly African American.

He was laid off from the mill in 1984, a year after he was arrested on charges of throwing a paint bomb at a strike-breaker’s car.

Despite not having a bachelor’s degree, Ignatiev was accepted to the Harvard Graduate School of Education. He received a master’s in 1985, and a doctorate in the history of American civilization in 1994. He was later a fellow at Harvard’s W.E.B. Du Bois Institute. He was ever a controversial figure: In 1992, he called for the removal of a toaster oven — designated for kosher use only — that had been placed in one of Harvard’s dining halls, urging that the toaster should be “purchased privately, by contribution or subscription,” rather than by the university, which receives public funds. His contract as a tutor was not renewed.

He was a professor of liberal arts at the Massachusetts College of Art and Design. He is survived by his partner, Pekah Pamella Wallace; a brother and a sister; a son, John Henry Ignatiev, and a daughter, Rachel Edwards; and three grandchildren.

[As deputy managing editor for news, Sewell Chan oversees the foreign and national desks, the News Desk, the Data and Graphics Desk, the multiplatform copy desks, the audience engagement team, newsletters and the editorial library. He also works across departments to lift the quality and timeliness of the daily news report. Before joining the Times in September 2018, Chan worked for 14 years at the New York Times.]

Spread the word