If you were asked to name the defining moment of American history in the 19th century, more likely than not, your answer would be “The American Civil War.” This is an understandable response. The Civil War is ubiquitous in media depictions of that century and generations of students have learned to recognize the significance of Fort Sumter, Gettysburg, and Appomattox. Wars are dramatic events—deadly ruptures that invariably bring changes to political and social orders—and therefore attract a lot of scholarly and amateur interest. Yet for all the attention paid to the war itself, the Reconstruction Era is almost treated as an afterthought. For historian Eric Foner, the Reconstruction Era was nothing less than a second founding of the U.S. marked by the greatest expansion of constitutional rights since the document’s ratification. But this second founding has also left a complicated legacy littered with devastating reversals of justice that demand our continued attention today.

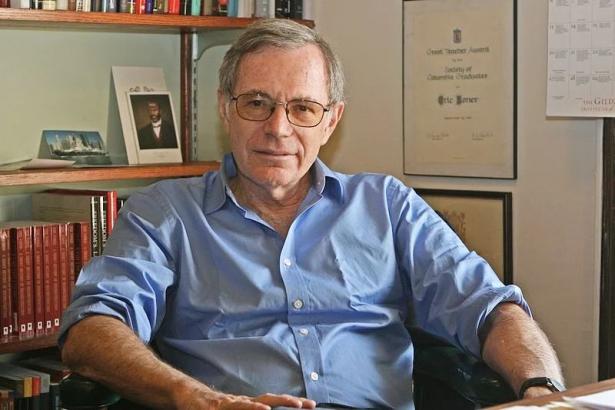

The lack of focus on the Reconstruction Era is one result of over a hundred years of students of American history being taught to scorn the “excesses” of its policies. The dominant narrative of the Dunning School—a group of scholars who critiqued the project of Reconstruction—was central to the idea of the South’s “Lost Cause,” and laid the rhetorical foundation for decades of Jim Crow laws. Central to this interpretation was the racist insistence that the enfranchisement of African Americans led to corruption and misgovernment throughout the former Confederate states. Even though dissenting scholars have discredited this bigoted school of thought, it has continued to thoroughly dominate popular discourse in the past century (from Birth of a Nation and President John F. Kennedy's book Profiles in Courage to comments made by Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton during the 2016 presidential campaign). This is where Eric Foner’s recently published book, The Second Founding: How the Civil War and Reconstruction Remade the Constitution, can help reorient our understanding of the period.

The Second Founding is exactly the right book to inspire a move towards a new appreciation of the Reconstruction Era as Foner wrote it with a mass audience in mind. Foner focuses his attention on the debates behind and significance of the passage of the three Reconstruction Amendments, the 13th, 14th, and 15th. Respectively, these three amendments are responsible for the abolition of slavery, the guarantee of birthright citizenship and due process of the law, and the prohibition of denying the right to vote based on race.

Readers, especially those less familiar with the Reconstruction Era, might be surprised to learn that these achievements were not driven by the altruistic spirit of the victorious Union. Foner shows that these three titanic, if flawed, achievements were products of the political calculus inherent in any legislative process. Therefore, the book doesn’t attempt to lionize the lawmakers of the late 1860s or create a new pantheon of “Founding Fathers” to venerate. Many of those in Congress who ultimately favored the passage of these amendments were not doing so because they believed in the equality of all people. Foner draws our attention to precisely how Congress drafted these three amendments to simultaneously extend rights to enslaved black men in the former Confederate states, while also preventing free blacks in the North from gaining too many rights. Even more striking were the ways in which lawmakers wrote them to prevent rights from being extended to other marginalized groups of the time, notably women, Native Americans, and Chinese immigrants in the Pacific states.

In addition to these three sections, Foner has a fourth chapter on the torturous judicial history that left these amendments stripped of their power to alleviate injustices for another century. Because of this, Foner’s telling of the history of Reconstruction is one of a brief triumph overshadowed by compromise and a political system that lost the desire to enforce the amendments in a way that might remedy racial discrimination. While the Civil Rights Movement did much to counteract this reluctance to enforce the Reconstruction amendments, it would be a mistake to say the struggle to create a truly interracial democracy is simply “in the past.”

This book’s sense of purpose comes from how clearly it argues that the fight for true equality begun over 150 years ago continues. Foner draws clear connections between the limitations and loopholes written into these 19th-century amendments and the most intractable debates dividing 21st-century America. The 13th Amendment abolished slavery, but by allowing for involuntary servitude to continue as punishment for a duly convicted crime, it has helped perpetuate vast inequities in the American criminal justice system. Vast systems of penal labor exploited this exception, entrapping black people in conditions that have been described as even worse than slavery. The 15th Amendment banned race-based discrimination at the polling place, but its narrow phrasing left loopholes for a number of other legalistic tricks to disenfranchise African Americans and other marginalized groups: poll taxes, grandfather clauses, literacy tests. Some might believe that this is a part of history Americans have left well behind—others would argue that strict “Voter ID” laws are merely a version of this phenomenon revamped for the 21st century.

The 14th Amendment has had the most complex history of the three, transitioning from an original intent to protect formerly enslaved African Americans into one that has been utilized by some interests and denounced by others. By the end of the 19th century, the U.S. Supreme Court placed the focus of the amendment largely on its commerce clause to protect corporate interests. Yet throughout the 20th century, the fight for greater women’s rights and an end to sex-based discrimination found legal standing thanks to the 14th Amendment. More recently, the 14th Amendment’s Due Process Clause also became the basis for the federal legalization of same-sex marriage around the same time that a contingent of Americans worried that its guarantee of birthright citizenship created an epidemic of so-called “birth tourism” and “anchor babies.” The questions raised by these amendments still resonate more than 150 years later.

Foner confidently asserts at the beginning of the book that “we are still trying to work out the consequences of the abolition of American slavery. In that sense, Reconstruction never ended.” Foner wants us to acknowledge that the Reconstruction Era is responsible for the constitutional rights that are most fiercely contested in the 21st century. This should encourage us all to teach Reconstruction and not just because it’s important to understand how history informs the present. We should teach Reconstruction because it empowers students to confront the legacies of slavery that persist into the present.

As we observe the 150th anniversary of the ratification of the 15th Amendment this year, now is the perfect time to deepen your knowledge of Reconstruction—or begin exploring it for the very first time. In addition to Foner’s masterful book, we invite middle and high school educators to use our seminal case study, The Reconstruction Era and the Fragility of Democracy, along with our rich array of accompanying lessons, videos, and primary sources.

Thomas Simpson is a Digital Marketing Specialist at Facing History and Ourselves. Thomas holds a master's degree in Global, International, and Comparative History from Georgetown University.

Give Now to Facing History. Make a 100% tax-deductible donation today and you'll help us reach even more teachers and students around the country, giving them the tools to fight back against hatred and bigotry.

Spread the word