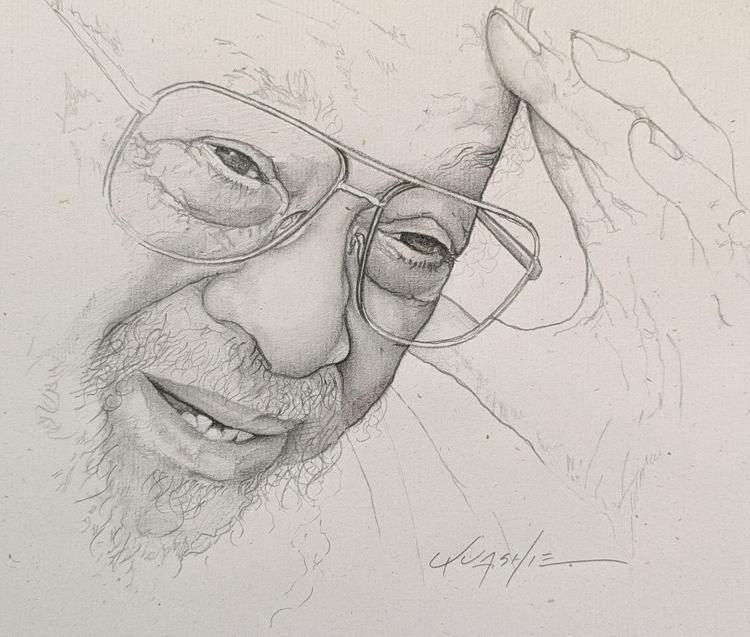

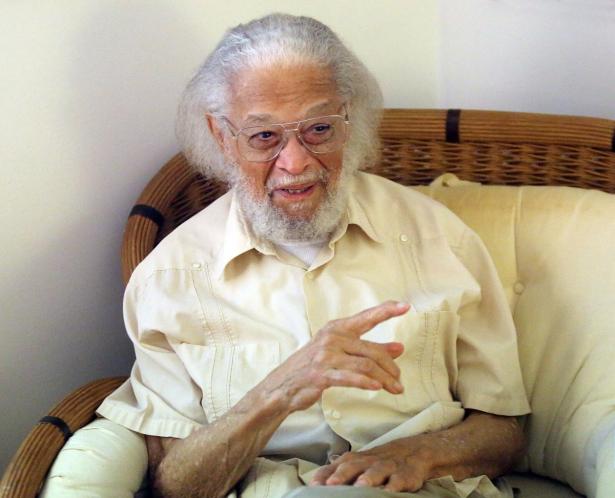

James Campbell is 95 years old, and it’s time for his favorite local artist to paint his portrait.

So one afternoon Colin Quashie visits Campbell at his James Island home to ask a few questions, to get to know the veteran activist better, to accumulate the ideas that ultimately will fuel his brush strokes.

Quashie paints in a realistic style. He likes to include the wrinkles and signs of arthritis, the manifestations of history on the human form. He captures on canvas his subject’s penetrating gaze in such a way that a viewer can recognize interior thought, consciousness, soul force.

Perhaps that’s why Campbell chose Quashie.

The two men have something else in common: a refined injustice detector. They are both animated by the distressing politics of social division and dedicated to exposing and condemning it.

The Post and Courier

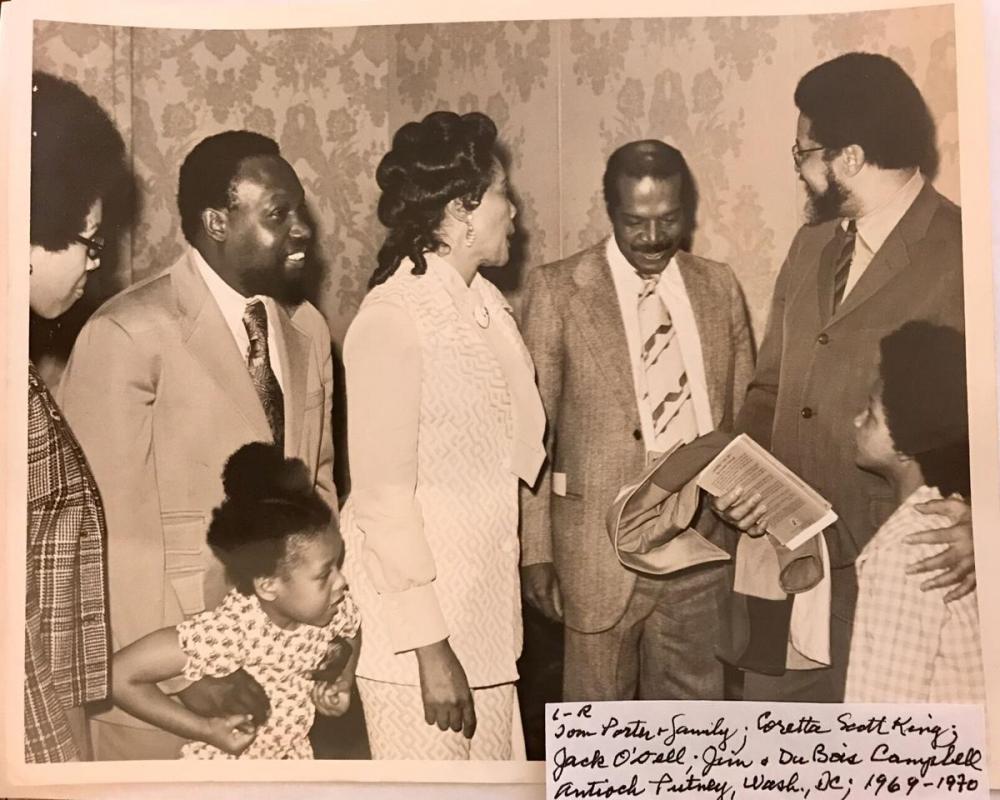

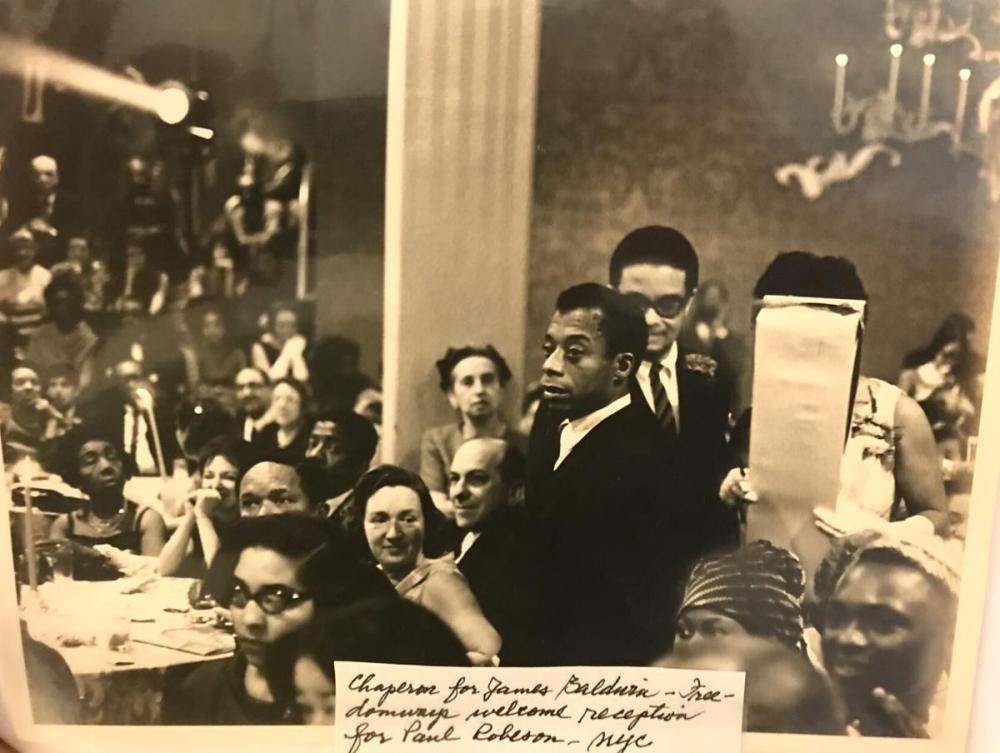

Campbell retired from the New York City school system and returned to Charleston in 1991, at 67 years old. Already he had accumulated more life experiences than most. He had helped to integrate the U.S. military, serving as a Montford Point Marine during World War II; he had worked in the civil rights movement befriending luminaries such as Jack O’Dell, Bayard Rustin, Malcolm X and Bob Moses. He had worked in the theater and contributed to the influential Freedomways journal co-founded by W.E.B. and Shirley Graham Du Bois.

He had also lived nine years in Tanzania, teaching and gaining a clearer understanding of post-colonial politics in that part of the world.

After his return home, Campbell kept busy mentoring young people, assisting Moses and Dave Dennis by advancing their Algebra Project initiatives in Lowcountry schools, joining the bioethics committee at the Medical University, working with local labor leaders to improve working conditions.

“You turn the pages of American history and his name is not on any page, but he was present,” notes Bobby Donaldson, professor of African American history at the University of South Carolina. “Talk about Malcolm X, Jim knew him well. Fannie Lou Hamer, Langston Hughes. How many people have letters from Langston Hughes in their collection?”

Indeed, James Campbell walks the walk.

On the path

Growing up in Charleston, in a cottage on President Street that eventually was demolished to make way for the Septima P. Clark Parkway, or Crosstown Expressway, he was a normal kid, playing in the yard, exploring the neighborhood, going to school.

His father, James Campbell Sr., was a farmer and railroad fireman from Hopkins, who moved to Charleston and became an ambulance driver for Roper Hospital, which catered to white patients. He also served as a driver for funerals. His mother, Eva Juliette Jones Campbell, graduated from the Avery Normal Institute in 1916, along with Septima Poinsette Clark, served as a teacher for a while, then devoted herself to family.

Campbell remembers playing in front of the house while his grandmother, Millie Cole, sat on the porch smoking a corncob pipe and seeing the distant past as clear as day. What she saw in her mind’s eye was her own mother, Eliza Davis, whipped by the slave master in the years before the Civil War, a scene she witnessed when she was perhaps 14 or 15 years old.

“It made me stop my play and just look,” he said.

The Campbells were members of the NAACP. They contributed to an African aid fund. They kept themselves informed and ensured their five children (Jim was the oldest) visited the Dart Library. Jim would sneak away sometimes to swim or fish, but the smell of pluff mud would give him away.

“You stinkin’ to high heaven!” his mother would admonish.

Young Campbell’s mother and his Aunt Sadie pushed him to learn, and eventually pushed him out of the dirt streets of Gadsden Green and onto a sturdier, if winding, path that led him far away from Charleston.

Brad Nettles/The Post and Courier

“They put ideas in my head about going away to school,” he said.

Voorhees Normal and Industrial Institute in Denmark, along with its students who hailed from Detroit, Philadelphia, Washington, D.C., and Columbia, opened his eyes. And his English teacher, Mrs. Catherine Booker, encouraged him to discuss ideas, interpret texts, think critically. She opened young Campbell’s mind.

Teaching and learning

In 1942, his senior year at Voorhees, he was drafted. He wanted to join the Air Force, but when he learned it was segregated, he joined the 52nd Marine Defense Battalion instead and prepared for war in the Pacific theater. He awakened to the violence of the world, drew connections between Nazi and Japanese tyranny and the African American experience.

He was about to ship out for the planned Japanese invasion when the U.S. dropped two atomic bombs, ending the war in the Pacific.

After he was discharged, he passed his GED tests and enrolled at Morgan State University in Baltimore, though his education was interrupted when he was called back to active duty during the Korean War. Again, he saw no action. Rather, he took courses, read books and became “anti-war,” he said.

At Morgan he majored in English and minored in theater, finding his way to the stage of the Arena Players and, eventually, securing an audition at the famed Actor’s Studio in New York City. He didn’t get in, but the idea of acting on Broadway took hold. After a couple of years of teaching in Baltimore, he left for the bright lights of the Big Apple in 1957, studied acting and found a part-time job serving summons for a small company run by a politically progressive Jewish man with whom Campbell engaged in conversations about American racism.

Then things started happening fast. He got his first substitute teaching job at a junior high school in the South Bronx, learned about the United Federation of Teachers and met all sorts of people.

“You’re either White or Black in the South,” he said. “But up north, there are Italians, Hungarians, Irish, Jews ...”

He excelled in his teaching career, securing permanent positions and working hard in the classroom during the day. In the evenings, he dashed downtown to attend acting classes. After a while, Campbell formed his own acting troupe, which presented one-act plays by Tennessee Williams, Thornton Wilder and others in the sanctuaries of churches and the gymnasiums of YMCAs.

The troupe eventually evaporated, but by then, Campbell was immersed in the civil rights movement.

Awestruck

In 1958, he came across a newspaper headline he liked, “Heed their rising voices,” and thought it would make a good button. Campbell visited Bayard Rustin of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference at his Harlem office with his offering. Rustin liked the idea but not the slogan and ended up changing the text, Campbell said.

Jack O’Dell was there and invited Campbell to help out in the office. O’Dell, a SCLC adviser and strategist and known leftist, was looking for a new place to live. Campbell had just moved into a big rent-controlled apartment, a fifth-floor walk-up at 135th Street and St. Nicholas Avenue, and was happy to rent a room to his new friend. It was largely through O’Dell that Campbell gained full access to the freedom movement and exercised his political intellect.

Campbell, meanwhile, was becoming fascinated with Malcolm X, who by 1963 was in an increasingly strained relationship with the Nation of Islam.

“I was starting to pay attention,” Campbell recalled. “I was impressed with his ability to speak to the working class.” After a 1964 rally in Harlem, he introduced himself. “I was impressed by how quiet and polite he was.”

Soon, Campbell, was designing the program for what he and Malcolm called a Liberation School, where small groups of students could learn about the African liberation movement, capitalism’s impacts and the power of enlightened thought.

One day, not long after Malcolm’s house had been firebombed, Campbell invited Malcolm to breakfast so he could meet Jack O’Dell. They chatted casually about this and that. Campbell asked Malcolm about his family.

“Brother, let me give you Betty’s telephone number, because you are someone I want her to stay in touch with,” Malcolm said, concerned for his wife and sensing his days were numbered. About one week later, he was murdered at the Audubon Ballroom.

Keeping busy

Campbell had been studying the writings of Julius Nyerere, the Tanzanian anti-colonial activist and politician, and decided in 1973 to go abroad.

He spent nine years there, teaching English first in Bihawana and then at the International School in Dar es Salaam.

He came back to Charleston in time to say farewell to his dying mother. He taught briefly at Burke High School then returned to New York, where he became assistant principal at two Harlem middle schools and then district coordinator for social studies until his retirement in 1991.

When he settled back in the Lowcountry after retirement, Campbell got involved in labor issues, working with members of the International Longshoremen’s Association; he joined the Medical University’s bioethics team as a member-at-large; and he became involved with Bob Moses’ Algebra Project. He also served on the advisory board of the College of Charleston’s School of Education, and was chairman of the education committee for the Charleston branch of the NAACP.

Mary Faith Marshall, director of the Center for Health Humanities and Ethics and director of the Program in Biomedical Ethics at the University of Virginia School of Medicine, remembers Campbell from her days leading the nascent bioethics program at MUSC.

She and her colleagues wanted someone on the committee who could provide an outsider’s perspective.

“Jim was just the perfect person,” she said. “He was such a delightful man, but he also brought the community to the table, which is really important. Ethics consultants are mostly clinicians who work in hospital and are acculturated to that life, we see things through lens that’s too narrow. Jim helped us ensure we had a broader view of the issues at hand and the people involved.”

This was especially important given the scandal underway at MUSC at the time. The institution was being sued for its policy of testing pregnant African American women for drug use. The lawsuit, Ferguson v. Charleston, eventually was appealed to the Supreme Court, which decided in favor of the women.

Marshall, armed with advice she received from Campbell, was subpoenaed and she condemned the racially motivated practice in her testimony, which cost her her job.

“(Jim) was the soul of the consult service and the ethics committee,” she said. “He gave folks a lot of courage, and a spine that they needed.”

It was Campbell who nominated Marshall for the Charleston NAACP’s Pathfinder Award.

“That is the most important honor I have ever gotten in my life, and that’s because of Jim Campbell,” she said.

Avery Research Center

Daron Lee Calhoun II, an administrator at the Avery Research Center who coordinates programming and the Race and Social Justice Initiative, called Campbell a mentor and role model who demonstrates the importance of research-based activism.

“Jim Campbell is the guy who made me the activist I am today,” Calhoun said.

So when the Avery received an anonymous donation in 2019, it used the money to bolster the Racial and Social Justice Initiative grant program, which provides students with financial awards and opportunities to learn teaching literacy, grant writing, social justice work, interviewing techniques and more, Calhoun said.

The student recipients would be called “Campbell Scholars.”

“Not only has he lived so long, it’s been a journey, a Great Migration story,” Bobby Donaldson of the University of South Carolina said. “Charleston to Denmark to Baltimore to New York to Africa. Through his own journey one could trace the diaspora.”

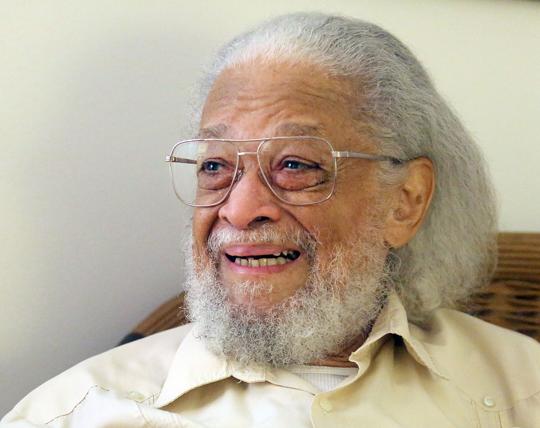

Now, at home, he sits in his wicker chair in the corner of his living room. Books and magazines are piled on the coffee table. Colin Quashie is there asking questions and taking pictures he can reference later as he sketches and paints. The master teacher, 95 years old, smiles and speaks of his life.

[Adam Parker has covered many beats and topics for The Post and Courier, including race in America, religion, and the arts. He is the author of “Outside Agitator: The Civil Rights Struggle of Cleveland Sellers Jr.,” published by Hub City Press. Contact Adam Parker at aparker@postandcourier.com or 843-937-5902.]

Spread the word