Reuven Kaminer left us on September 20, Rosh Hashanah 5781. He was my most important teacher and model for how to live a life of moral and political commitment. Over the course of decades, Reuven drew on his profound knowledge and political experience to teach many younger people about the Marxist critique of capitalism. His teachings and personal example inspired generations of activists who have maintained a lifetime of political engagement in Israel and around the world.

Reuven taught us that political practice should be informed by theory. He had great respect for scholarship, worked for much of his life in academic administration, and retired with the title of Vice Provost of the School for Overseas Students at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. But Reuven always insisted that scholastic theory without practice is sterile. For more than half a century he participated in every important political battle in Israel. He was a central figure in several radical left organizations and broader coalitions, usually exercising leadership by his influence on others whose public presence was more prominent.

Reuven and his wife, Dafna, immigrated to Israel from Detroit in 1951. His departure from the United States was hastened by his desire to avoid being drafted into the U.S. Army to fight during the Korean War. They were members of the socialist Zionist Hashomer Hatzair youth movement and joined Kibbutz Sa’ar in the western Galilee. Hashomer Hatzair, its kibbutzim, and their urban allies were the largest component of Mapam (the United Workers Party), which was established in January 1948.

From Soviet dogmatism to independent thought

Understanding the Kaminers’ political trajectory requires bracketing the contemporary left’s nearly universal distaste for Soviet-style Marxism, while foregrounding the context of the Cold War internationally and the imposition of military rule over Palestinian citizens of Israel by Mapai-led governments from 1949 to 1966. During the Cold War, the Soviet bloc provided crucial support for the decolonizing countries of the Global South: Cuba, Algeria, Vietnam, the African National Congress of South Africa, and many others. It was the most substantial force opposing the global ambitions of U.S. imperialism.

The Communist Party of Israel (Maki) accepted Palestinian Arabs as full and equal members in both rank-and-file and leadership positions. It consistently advocated for their full democratic rights, opposed the expropriation of their land, and demanded an end to the military government. Maki rejected the Israeli national consensus on “security,” and was the only party to oppose Israel’s alliance with French and British imperialism in their war of aggression against Egypt over the Suez Canal in 1956.

Mapam, meanwhile, was an unstable coalition comprised of Marxist-Zionist movements that opposed the dominant position of Israel’s Mapai party (the precursor of today’s Labor Party). It contained Hashomer Hatzair members who had abandoned their call for a binational Jewish-Arab state in Palestine to form Mapam. Among them were advocates of pro-Soviet Marxism-Leninism, and militarists of the Hakibbutz Hameuchad movement who formed the core of the pre-state Palmach militia, denied the Palestinian right to national self-determination, and refused to admit Arabs as party members.

In late 1952, Mapam was facing a crisis. A prominent member of its pro-Soviet faction, Mordechai Oren, was arrested in Czechoslovakia and put on trial along with Rudolf Slansky and other mostly Jewish Czech Communist Party leaders, who were charged by pro-Soviet Czech authorities with being Jewish bourgeois nationalists and Zionist agents. Most of Mapam’s leaders denounced the Slansky trial as an antisemitic frame-up.

In late 1952, Mapam was facing a crisis. A prominent member of its pro-Soviet faction, Mordechai Oren, was arrested in Czechoslovakia and put on trial along with Rudolf Slansky and other mostly Jewish Czech Communist Party leaders, who were charged by pro-Soviet Czech authorities with being Jewish bourgeois nationalists and Zionist agents. Most of Mapam’s leaders denounced the Slansky trial as an antisemitic frame-up.

Fritz Cohen // +972 Magazine

Moshe Sneh, a leader of the pro-Soviet faction, chose “the world of revolution” (meaning the leadership of the Soviet Union) over Zionism and formed a “Left Section” in Mapam. Reuven and Dafna joined the Left Section. Consequently, in 1953, along with some 200 other members of Hashomer Hatzair kibbutzim, the couple were expelled from their kibbutz for their political views. In the cities, Sneh and his followers were expelled from Mapam and established the Left Socialist Party. Reuven, Dafna, and their infant son, Noam, who passed away in 2014, moved to Jerusalem and joined the party. The Left Socialist Party lasted only a year and a half. In October 1954 most of its members, among them Reuven and Dafna, joined Maki.

Maki split in 1965. An entirely Jewish faction led by Shmuel Mikunis and Moshe Sneh sought to join the Zionist consensus on “security” matters and to draw closer to Mapam. It kept the party name. A mainly Arab faction led by Tawfik Toubi and Meir Vilner saw the Arab states aligned with the Soviet Union — Egypt, Syria, and Iraq — as the leading anti-imperialist forces in the Middle East. They adopted the name Rakah (the New Communist List). A few years earlier, a mostly Jewish group had left Maki to form the Israeli Socialist Organization (Matzpen). They largely shared Rakah’s analysis of the region, but foregrounded the ideological struggle against Zionism in a way that utterly marginalized them in the Israeli political arena.

Reuven and Dafna joined the Maki faction, and Reuven served as the secretary of the party’s Jerusalem branch. After the 1967 War, they and several others left Maki because the party embraced the Israeli national consensus that the war had been a justified war of self-defense. Today, books by Tom Segev, Guy Laron, and Uri Ben-Eliezer are available to refute this consensus based on substantial archival evidence. In 1967, rejecting the Israeli consensus on the war was an act of extraordinary political bravery and an exceptional capacity for independent political analysis. Opposing the war was easier for Rakah, which simply followed the Soviet line. Those who left Maki after 1967 also sought a new socialist path beyond dogmatic pro-Sovietism.

In 1968, Reuven, Dafna, and others from their circles joined with university students born in Hashomer Hatzair kibbutzim who rejected Mapam’s drift to the right to establish Siach (Smol Yisra’eli Chadash – Israeli New Left). In his book, “The Politics of Protest: The Israeli Peace Movement and the Palestinian Intifada,” Reuven characterized Siach as “the major force of the student left in the 1968–1973 period.”

Challenging socialist Zionism

I didn’t know any of this personal/political history when I first met Reuven and Dafna. In 1970, a few months after we were married, my wife Miriam and I emigrated to Israel in the framework of Hashomer Hatzair. I was about to be drafted into the U.S. army and would likely have been sent to Vietnam after basic training. Reuven and I shared our refusal to fight for U.S. imperialism before we met.

We settled with a large group of North Americans on Kibbutz Lahav, about 20 kilometers north of Be’er Sheva. The kibbutz members shocked us with their militarism, racism, traditionalist gender norms, and lack of concern for the fact that Lahav is situated on the ruins of three Palestinian villages, one of which could be seen from the entry to the communal dining room. Contrary to the ideology of Hashomer Hatzair, Lahav employed two Bedouin citizens who worked on lands formerly owned by one of their families. It did not take long to realize that the kibbutz was not, as we were taught in Hashomer Hatzair, the vanguard of Israeli socialism and had nothing at all to do with internationalism (achvat amim, in Hashomer Hatzair’s vocabulary). But beyond that, we did not have the tools to understand Israeli society and politics.

After less than a year, Miriam and I left the kibbutz and moved to Jerusalem. Since I was interested in graduate study, our friend Baruch Fischhoff, who was then a doctoral student at the Hebrew University, recommended that I seek out Reuven.

Courtesy of the Kaminer family // +972 Magazine

Reuven and Dafna welcomed us into their home and fed us, physically and emotionally. Reuven hired me to work as a translator in his department at what was then the Hebrew University’s Office of Overseas Students. While the income was helpful, more importantly, he taught me to write clear and succinct English. Reuven and Dafna also introduced us to Siach, which became our political and social framework.

Like many new left organizations around the world in the late 1960s and early 1970s, Siach had no comprehensive ideology, no elected leadership, and no clearly defined criteria for membership. Whoever came to its often prolonged weekly meetings participated equally in discussions and decision-making. This was an excellent way for a new immigrant, as several of us in Jerusalem Siach were, to absorb university-level Hebrew and learn things about Israel that were not taught in Zionist youth movements.

Some Siach members sought to revive what they believed to be the untainted socialist Zionism of the early 1950s Mapam. Others, including Reuven and Dafna, defined themselves as non-Zionists. I was initially attracted to this view because its advocates saw the IDF as an army of conquest and occupation that should be confronted, not a “people’s army” whose orders to disband demonstrations must be obeyed. But the non-Zionists rejected a strategy of conducting a struggle around Zionist ideology and generally advocated forming coalitions with any groups that agreed on a particular action without imposing ideological litmus tests.

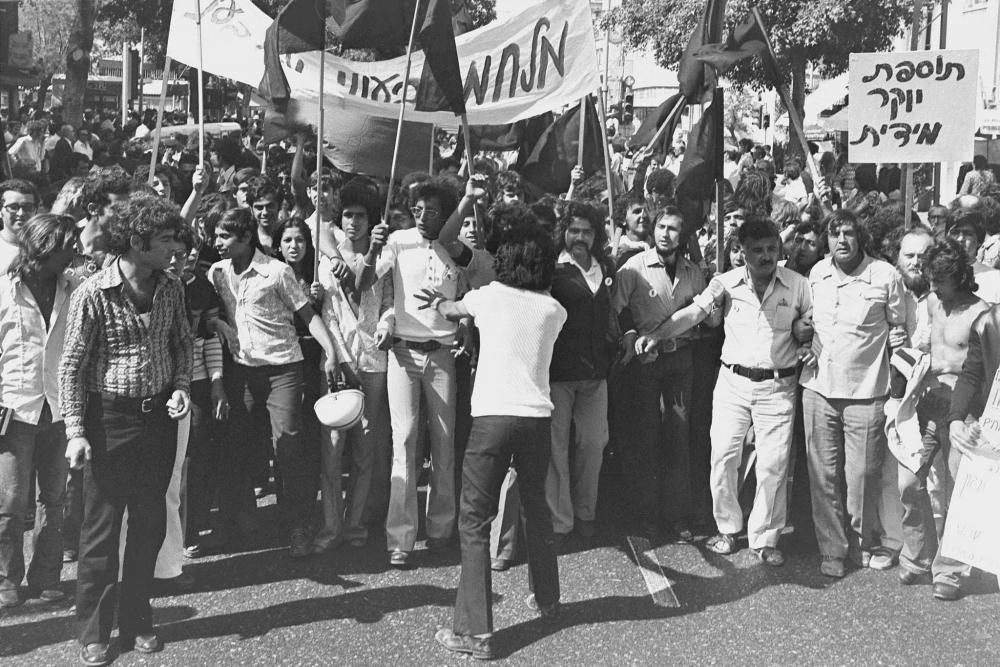

In 1971-73, when we were active in Siach together, the organization focused on two issues: opposing the Israeli occupation of the West Bank, East Jerusalem, and the Gaza Strip, and solidarity with the Israeli Black Panthers, who were organizing against the state’s racist policies toward Mizrahim.

Moshe Milner // +972 Magazine

Siach practiced direct action, much of it illegal: painting slogans on walls and participating in illegal demonstrations (the police would not give permits to protest in central Jerusalem). Unlike most of the other older members of Siach, Reuven encouraged direct action, although he usually let younger people take the lead. Whenever we went out to do something risky, he would give us the phone number of the Kaminer home in Jerusalem’s Kiryat Hayovel neighborhood to call if there was trouble. I still remember the number half a century later, perhaps because in many respects, I thought of the Kaminer home as my anchor in an Israel that was not the Jewish national home I had hoped for.

In 1972, members of Jerusalem Siach made contact with students from Birzeit University in the West Bank and traveled there for a joint meeting. Some members of Siach strenuously opposed this meeting because we did not have a political certificate of health ensuring that none of the Palestinian students supported terrorist organizations. Those of us who organized and attended the event believed that meeting our Palestinian counterparts and listening to their experiences of the occupation was a necessary step to deepen the struggle against the occupation. Reuven supported us.

Many younger members of Siach adopted the typical left lifestyle of “sex, drugs, and rock and roll.” Reuven and Dafna never participated in any of this, although I remember them attending a few parties. Unlike several of the other older members of Siach, Reuven was tolerant of the follies of youth. He had confidence in us, and I loved him for that.

As he did throughout his life, Reuven invited several members of Jerusalem Siach to study Marxist texts. “The Bolshevik cell,” as we were known, met every Shabbat in the Kaminer home to read Marx, Lenin, Marcuse, and others. We often read line by line, as if we were studying Talmud. So not only did Reuven teach me how to write, he taught me, and many others, how to read. When I became a university professor a decade later, I tried to teach my students close critical reading, just as Reuven had taught us.

After studying, Dafna fed us, and we watched basketball. This combination of intellectual and social stimulation, physical sustenance, and the context of the intense experiences of the broader Jerusalem new left, prefigured the socialist community we imagined for the future. It left an indelible mark on me, although we did not, and could not possibly have realized our vision in that time and place.

From Birzeit to Romania

Miriam and I returned to the United States in 1973. I refused to serve in Israel’s army of occupation, and the Jerusalem police were conspiring to try me on false non-political charges that might have landed me in prison for three years.

Siach also broke up in 1973 over disagreements about participating in electoral politics and Zionism/non-Zionism. When the smoke from that struggle cleared, Reuven and Dafna were among the founders of Shasi (Israeli Socialist Left) which, during its existence from 1975 to 1991, was an important home for the independent left. Shasi was an organization of political radicals who rejected both the Zionist Israeli national consensus and the oppositional ideology constructed around Soviet communism. Reuven was a distinctive figure in Shasi and one of the few members with a deep knowledge of Marxist theory. When Shasi was established, he already had nearly a quarter of a century of experience in political struggle in Israel.

Siach’s effort to find Palestinian partners at Birzeit University in 1972 had minimal results. But later in the decade, several Birzeit faculty members established strong personal ties with their Israeli counterparts, among them the late Daniel Amit, a physicist at the Hebrew University. This led to the establishment of the Committee for Solidarity with Birzeit University in November 1981 — a response to the university’s closure by the occupation authorities. Shasi members and supporters were an important component of the committee and participated in its joint demonstrations with Palestinians in Ramallah, Birzeit, and Bethlehem.

In a symbolic direct action, hundreds of Israelis secretly entered the campus to “reopen” Birzeit University. These militant actions won the respect of Palestinians and made headlines in Israel. Reuven was exceptionally proud of the committee’s work and considered it “the widest and most unified combination of forces to the left of Peace Now ever put together.” The committee was a key building block of Israeli Jewish solidarity with the First Intifada, which broke all the taboos about political action in support of Palestinian rights.

Shasi was also among the first groups to oppose the 1982 Lebanon War. Its members, prominent among them Reuven and Dafna’s son Noam, helped to popularize refusal to serve in the IDF: in Lebanon, in the occupied territories, or altogether. Shasi further insisted that Israel should negotiate with the Palestine Liberation Organization to advance a two-state solution.

Andra Bertman, Hashomer Hatzair archives, Givat Haviva // +972 Magazine

Convinced of the importance of direct dialogue with Palestinians, in 1986 Reuven joined a delegation of 30 Israelis that met with representatives of the PLO in Romania. Reuven and three other members of the delegation were tried and convicted (but given light sentences of community service) for violating the Israeli law prohibiting such meetings. It took seven more years before direct Israeli negotiations with the PLO were accepted as the way to achieve peace. Had they occurred in the 1970s or 1980s, the outcome may well have been very different than the disappointing Oslo process.

After Siach was disbanded, Reuven decided to join the Jerusalem branch of Peace Now. For several years he worked to push Peace Now to be more critical of the Rabin government’s implementation of the 1993 Oslo Accords in a way that ultimately blocked, rather than facilitated, the establishment of a Palestinian state.

In 2003, after the outbreak of the Second Intifada, Reuven and Dafna’s grandson Matan Kaminer, along with +972 executive director Haggai Matar, Noam Bahat, Adam Maor, and Shimri Tzameret announced their refusal to be drafted into the IDF. They were incarcerated in a military prison for 14 months before being sentenced to an additional 12 months’ imprisonment. Reuven and Dafna helped to establish the Refusers’ Parents Forum, which educated the public about the case and organized solidarity demonstrations. In 2016, Reuven and Dafna’s granddaughter, Tair Kaminer, also announced her refusal to be drafted. She was released after serving more than five months in prison, the longest of any female draft refuser.

photo: Oren Ziv/Activestills.org // +972 Magazine

The political organizations that Reuven Kaminer belonged to throughout his life did not succeed in the conventional sense of the word. But their actions indelibly changed Israeli society. Members of Siach participated in the first feminist consciousness-raising group in Jerusalem. Although Siach and Shasi were among the first Israeli leftist organizations to raise the issue of gender, their understanding of the issue was very limited compared to the more sophisticated treatments of Nira Yuval-Davis, Simona Sharoni, Henriette Dahan Kalev, Aida Touma-Suleiman, Maisam Jaljuli, and others.

Siach strongly supported the Black Panthers. Many of us were among the dozens arrested at the large Panther demonstration in Jerusalem on the occasion of the 28th Zionist Congress in January 1972. Maki, Siach, and Shasi all addressed the issue of the racist oppression of Mizrahim in Israel. But none of these organizations developed an adequate theorization of this issue as a central component of the Zionist project in the style of Ella Shohat or Yehouda Shenhav.

Members of Siach and Shasi, and the various coalitions in which they participated, broke many taboos by upholding the national rights of the Palestinian people and supporting the creation of a Palestinian state alongside Israel. That now seems all but impossible. Yet the principles of decolonization and equality, dignity, and justice for all who live between the Jordan River and the Mediterranean Sea remain on the agenda of many of those who Reuven taught and inspired.

[Joel Beinin is the Donald J. McLachlan Professor of History and Professor of Middle East History, Emeritus at Stanford University. His research and writing focus on the social and cultural history and political economy of modern Egypt, Palestine, and Israel, and the Palestinian-Israeli Conflict.]

Spread the word