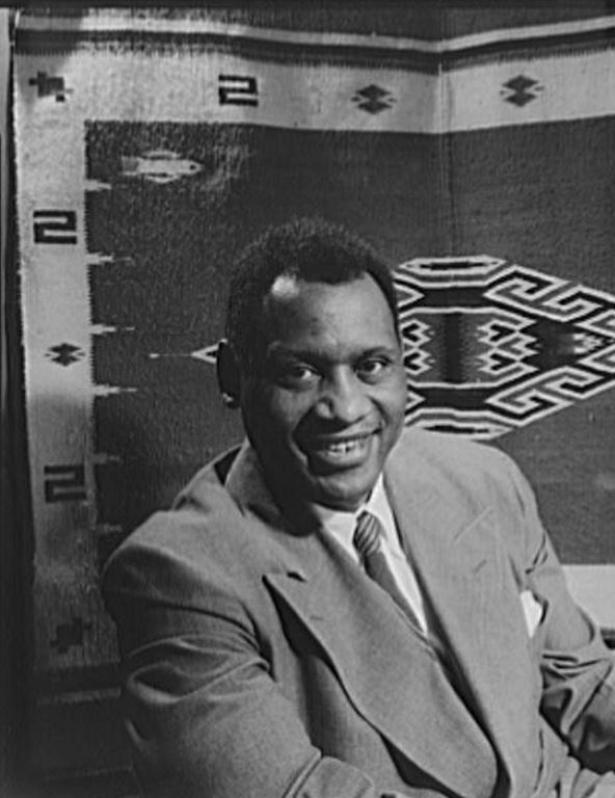

Paul Robeson (1898-1976) was the most talented person of the 20th century. He was an internationally renowned concert and opera singer, film star and stage actor, college football star and professional athlete, writer, linguist (he sang in 25 languages), scholar, orator, lawyer, and activist in the civil rights, labor, and peace movements. In the 1930s and 1940s, Robeson was one of the best-known, and most admired, Americans in the world. Today, however, he is almost a forgotten figure. Few Americans know his name or accomplishments.

We are familiar with authoritarian governments that seek to “erase” the memory of prominent critics, but how can it happen in a democracy like the United States? Starting in the late 1940s, as the Cold War escalated, America’s political establishment began an assault on Robeson’s career and reputation because of his political activism and outspoken radicalism. He was blacklisted, his concerts and recording contracts canceled, and his passport revoked. By the mid-1950s, he had become a marginal figure — emotionally depressed, physically exhausted, and politically isolated.

Every so often it looks like Robeson might be getting the revival that is long overdue. Since his death in 1976, his admirers have attempted to restore his visibility. They’ve produced biographies, plays, and documentary films exploring Robeson’s talents and examining his legacy. Each of these efforts has made some progress in lifting Robeson out of obscurity, but his reputation still has not recovered from its political silencing.

Other public figures who challenged the political status quo — including Albert Einstein, W. E. B. Du Bois, Eleanor Roosevelt, Muhammad Ali, and Martin Luther King Jr. (who was viewed unfavorably by 66 percent of Americans in a 1966 Gallup poll) — were also attacked by red-baiters and conservatives, but their reputations outlasted their critics. Not Robeson. He is, at best, a footnote in history textbooks, little known outside a small circle of Americans with a special interest in the history of the civil rights and left-wing movements, although somewhat better known among African Americans than white Americans.

We are currently in the midst of a bit of a Robeson resurgence, however. Keith David performed his one-man show, Paul Robeson, directed by its playwright Phillip Hayes Dean, at the Ebony Repertory Theatre in Los Angeles in March and April this year. Another one-man show about Robeson, The Tallest Tree in the Forest, opened April 12 and goes through May 25 at The Mark Taper Forum in Los Angeles, with music written and performed by Obie Award–winner Daniel Beaty. A new book, Paul Robeson: A Watched Man (Verso), by Jordan Goodman, supplements Martin Duberman’s magisterial 1989 biography, Paul Robeson.

Robeson’s story is so incredible — indeed, mythic — that it would seem to be the stuff of fiction if there weren’t so many records, films, news clippings, Congressional testimonies, and memoirs by his friends, collaborators, and enemies to document its reality. His almost superhuman achievements, his rise from humble origins to great heights, only to fall, tragically, to ignominious depths — his amazing life seems like a fable, the moral of which has been subject to many different interpretations, each shaped by the political orientation of the interpreter.

Robeson’s Background and Fame

Robeson’s mother, a teacher, died when he was six. His father, the Reverend William Drew Robeson, escaped from slavery at age 15 in 1860, raised Paul and his four older siblings, and served as pastor of a church in Princeton, New Jersey, until the church’s white elders fired him for speaking out against social injustice. For a while he worked as a coachman but eventually managed to find other pulpits.

After excelling in academics and sports in high school, Robeson attended Rutgers, then a private college, on a scholarship in 1915. He was the third black student at Rutgers and its first black football player. His own teammates roughed up the six-foot-three Robeson on the first day of scrimmage, and he constantly endured racial slurs and physical harassment from opposing players. His father had impressed upon him, he later recalled, that he was not there on his own but rather was “the representative of a lot of Negro boys who wanted to play football and wanted to go to college.”

Robeson was elected to Phi Beta Kappa in his junior year and was the valedictorian of his 1919 graduating class. He won the Rutgers oratory award four years in a row. Although a member of the college glee club, he was not allowed to travel with the group or participate in its social events. He earned varsity letters in football, baseball, basketball, and track. He was twice named to the College Football All-America Team, but he was benched when Rutgers played Southern teams, who would not take the field with a black player playing for the opposing team. A “class prophecy” in the college yearbook predicted that by 1940 he would be the governor of New Jersey as well as “the leader of the colored race in America.”

After graduation, Robeson moved to Harlem and studied law at Columbia University. He helped pay for law school by playing professional football for the Akron Pros of the American Professional Football Association in 1921 and for the Milwaukee Badgers of the newly formed National Football League the following year. After earning his law degree in 1923, he took a job at a private law firm, but his supervisors made it clear that he would never be considered a professional equal. The last straw was a white secretary’s refusal to take dictation from him. He quit and never practiced law again.

While Robeson was in law school his wife, Eslanda, persuaded him to perform in small theater roles, and he quickly began a new career as an actor and concert singer. In 1924, a year out of law school, he got the lead in Eugene O’Neill’s All God’s Chillun Got Wings at a Greenwich Village theater. Critics praised Robeson’s performance, but he could not find a restaurant — even in that liberal bohemian neighborhood — that would serve him. Next he played the central character in O’Neill’s The Emperor Jones, about an ex-convict who escapes to a Caribbean island and sets himself up as emperor. The following year, Robeson launched his career as a concert singer with a recital of Negro spirituals, helping inject those spirituals into the American songbook. From that point on, his solo concerts and recordings were the core of his work as a performer, even as he won increasing fame as an actor on stage and in film.

Robeson had a powerful bass-baritone voice and a commanding presence on stage. He was tall, handsome, and self-confident. He performed with dignity, even in the demeaning and stereotypical roles available to black actors at the time.

In 1928, Robeson was invited to sing the part of Joe in the London production of Show Boat (by Jerome Kern and Oscar Hammerstein II), which had been a huge hit in New York. The musical chronicles the lives of people working on a Mississippi River showboat, and its black characters reflected the era’s stereotypes. Robeson’s rendition of “Ol’ Man River” was a showstopper and became one of his trademark songs throughout his career. In the London show he sang the original lyrics, which begin “Niggers all work on the Mississippi.” Within a few years, when performing the song in concerts, he changed the first word to “darkies.” And when he made the film version in 1936, he transformed the opening line entirely to “There’s an ol’ man called the Mississippi; that’s the ol’ man I don’t like to be.” He also eventually changed the line “I’m tired of livin’ and feared of dyin’” to the more militant and political “I must keep fightin’ until I’m dying.”

Although Robeson disliked most of his film roles for reinforcing negative stereotypes of Africans and African Americans, a few of them allowed him to play parts several notches above the stereotypical parts available for black actors. In The Proud Valley, he played David Goliath, a black American miner who gets a job in a Welsh mine, joins a male choir made up of other coal miners, and eventually dies in a mine accident while saving his fellow workers. This independently produced movie, filmed on location in the Welsh coalfields, documents the harsh realities of coal miners’ lives and showed Robeson’s character in particular in a positive light, allowing him to merge his artistic talent and his political views.

In 1930 he became the first black man in almost a century to play Othello in England. It would be another 13 years before he performed the role in the United States, in 1943. Even then, having a black man play a romantic lead, especially with a white woman as Desdemona, was controversial. Still, the production ran for 296 performances, a record for a Shakespeare play on Broadway.

Robeson’s Growing Radicalism

Robeson and his family spent much of the 1930s living in England and traveling and performing throughout Europe. In England he faced less overt racial prejudice and greater social acceptance than in the United States. In London he met Jomo Kenyatta and other young Africans who would soon lead independence movements, triggering Robeson’s awareness of the emerging struggles by nonwhite peoples against colonialism. In 1934 he visited Germany, where the Nazis had just taken power, and said the atmosphere felt like a “lynch mob.” He donated money to Jewish refugees fleeing Hitler’s Germany. That same year he visited the Soviet Union and was impressed by the lack of racial bigotry he perceived there.

His travels awakened his political consciousness. As his fame grew, Robeson filled the world’s largest concert halls and used his celebrity to speak out on political issues. He increasingly aligned himself with leftist movements in the United States, Europe, and Africa. At a 1937 rally for antifascist forces fighting in the Spanish Civil War he declared, “The artist must take sides. He must elect to fight for freedom or slavery. I have made my choice. I had no alternative.” In New York in 1939 he starred in a network radio premiere of Earl Robinson’s “Ballad for Americans,” a patriotic cantata that celebrated America’s racial and ethnic diversity and its tradition of dissent. Robeson and Bing Crosby each recorded the piece, which was so popular that it was performed at both the Republican and Communist Party conventions in 1940.

Robeson routinely challenged racial barriers to draw attention to blacks’ second-class citizenship. In July 1940, 30,000 people packed the Hollywood Bowl to hear Robeson accompanied by the Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra. But no major Los Angeles hotel would accommodate Robeson. Eventually the Beverly Wilshire Hotel agreed to lodge the singer, but at the then-exorbitant rate of $100 per night and only if he would register under an assumed name. Robeson accepted those terms but then defiantly spent every afternoon sitting in the hotel lobby, where he was widely recognized. Soon thereafter, Los Angeles hotels lifted their restrictions on black guests.

During World War II, Robeson was at the height of his fame. His concerts of Negro spirituals and international songs drew huge audiences. His recordings sold well. In polls, Americans ranked Robeson as one of their favorite public figures. He entertained troops at the front, sang battle songs on the radio, and was a frequent presence at rallies and benefits for the war effort as well as left-wing causes. On December 22, 1941, just a few weeks after the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor, Robeson spoke at a “Defend America Rally” in Los Angeles, sponsored by the National Negro Congress, and called on the black community to mobilize on behalf of the war. On September 15, 1942, at the invitation of the United Auto Workers union, Robeson spoke and sang for 10,000 workers at the North American Aircraft factory in Inglewood, a Los Angeles suburb. Two days later, he performed at a “Win the War, Defeat Jim Crow” rally at Los Angeles’s Philharmonic Auditorium, sponsored by the Council on African Affairs. Indeed, Robeson gave many recitals, often without pay, for groups supporting the war. At every event, he would call for the dismantling of racial discrimination in the defense industry and the military.

In 1943, Robeson headed a delegation of blacks who met with the baseball commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis and major league baseball owners to demand the desegregation of baseball. (The Brooklyn Dodgers signed Jackie Robinson to a contract two years later.) In 1945 he headed an organization that challenged President Harry S. Truman to support an antilynching law.

When World War II ended and the Cold War began, Robeson’s outspoken support for the Soviet Union became highly controversial. His biographer Martin Duberman suggests that privately Robeson had begun to have doubts about the Soviet Union, particularly its mistreatment of Jews. When he visited Russia in 1949, he insisted on seeing his friend Itzik Feffer, a Jewish writer, whom the Soviets had arrested. Feffer told him about widespread official anti-Semitism in the Soviet Union, including the arrests and show trials. At his concert in Moscow, Robeson made a point of talking about Feffer and then singing, in Yiddish, the anthem of the Warsaw Ghetto resistance, clearly a statement of solidarity with Russian Jewish dissidents. But when speaking in the United States, Robeson never uttered any criticism of the Soviet Union, fueling criticism of him as a Soviet apologist.

Once he was asked why, being so critical of the United States, he did not move to the Soviet Union. “Because my father was a slave, and my people died to build this country,” Robeson said, “and I am going to stay right here and have a part of it.”

Despite the growing attacks on the Left, Robeson maintained an exhausting schedule of concerts and speeches on behalf of radical causes. In September 1947, he took the stage at Los Angeles’s Shrine Auditorium at an event sponsored by the Spanish Refugee Appeal to raise money for a hospital in Toulouse, France, where all the patients were refugees who had fought against General Francisco Franco’s fascist forces in the Spanish Civil War. In February 1948, he performed at Los Angeles’s Second Baptist Church, sponsored by the CIO United Public Workers, the Civil Rights Congress, and the State, County & Municipal Employees union, to launch a campaign in support of a federal Fair Employment Practices Act, antilynching and anti-poll tax legislation, and to oppose the growing witch hunts and purges of radicals from government, teaching, show business, and other sectors.

In 1948, Robeson campaigned enthusiastically for Henry Wallace’s presidential campaign. The former US vice president had been dumped from the 1944 Democratic Party ticket by President Franklin Roosevelt for his radical views. So four years later Wallace ran against President Harry Truman (who took office after FDR’s 1945 death) on the Progressive Party ticket on a platform that emphasized opposition to the Cold War, strong support for labor unions, and a commitment to racial integration.

Robeson and the Red Scare

The attacks on Robeson escalated dramatically after he spoke at the Congress of the World Partisans of Peace in Paris in 1949, attended by leftist writers, artists, and intellectuals from around the world. There Robeson said that American workers, white and black, would not fight against Russia or any other nation. In the United States, however, the media misreported his remarks, interpreting them to mean that black Americans would not defend the United States in a war against the Soviet Union.

After that, it was open season on Robeson. He was denounced by the media, politicians, and conservative and liberal groups alike as being disloyal to the United States and a shill for the Soviet Union. Major civil rights groups — eager to avoid the taint of communism — distanced themselves from Robeson, who had received the Spingarn Medal, the highest award given by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, only four years earlier.

In 1949 Brooklyn Dodgers owner Branch Rickey orchestrated Jackie Robinson’s appearance before the House Un-American Activities Committee so that he could publicly criticize Robeson. Robinson criticized American racism but also, as expected, challenged Robeson’s patriotism. “I and other Americans of many races and faiths have too much invested in our country’s welfare for any of us to throw it away for a siren song sung in bass,” Robinson said.

Right-wing groups violently disrupted the few concerts he performed, sponsored by progressive and leftist groups, such as a benefit concert for the Civil Rights Congress in Peekskill, New York, in August 1949. The following month, Robeson was scheduled to perform at a concert in Los Angeles sponsored by the California Eagle, the progressive African-American newspaper run by activist Charlotta Bass. In anticipation of that event, the Motion Picture Alliance for the Preservation of American Ideas (the Hollywood studios’ blacklisting arm) published ads red-baiting Robeson, while the Los Angeles City Council passed a resolution calling Robeson’s concert “an invasion” and unanimously adopted a resolution urging a boycott. In response, Robeson’s supporters flooded the Council with angry protests and on September 30 filled 16,000 seats at the Wrigley Field concert.

In 1950 the State Department revoked Robeson’s passport, claiming that his travel overseas would be “contrary to the best interests of the United States.” The loss of his passport prevented him from performing in Europe and Australia, where he was still enormously popular. His American concerts were canceled, too. Record companies stopped recording him. NBC barred Robeson from appearing on a television show with Eleanor Roosevelt. He received frequent death threats. Blocked from performing regularly, Robeson’s income declined from $100,000 in 1947 to $6,000 in 1952.

On June 12, 1956, at the height of the Cold War, Robeson — his mental health along with his income suffering from the blacklist — was called to testify before the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), ostensibly about the revocation of his passport. Robeson refused to answer questions about his political activities. Instead, he defiantly challenged his inquisitors, ridiculing them for violating his rights.

HUAC Counsel Richard Arens asked, “Are you now a member of the Communist Party?” Robeson responded: “Would you like to come to the ballot box when I vote and take out the ballot and see?”

During his testimony, he lectured committee chair Representative Francis Walter of Pennsylvania, insisting that his passport was revoked because, at home and abroad, he spoke out in favor of the independence struggles of African and Asian peoples and against injustices against African Americans.

“I am being tried for fighting for the rights of my people, who are still second-class citizens in this United States of America,” Robeson said.

My mother was born in your state, Mr. Walter, and my mother was a Quaker, and my ancestors in the time of Washington baked bread for George Washington’s troops when they crossed the Delaware, and my own father was a slave. I stand here struggling for the rights of my people to be full citizens in this country. And they are not. They are not in Mississippi. And they are not in Montgomery, Alabama. And they are not in Washington. They are nowhere, and that is why I am here today. You want to shut up every Negro who has the courage to stand up and fight for the rights of his people, for the rights of workers, and I have been on many a picket line for the steelworkers too. And that is why I am here today.

As the hearing was winding down, Robeson looked at the HUAC members and told them: “You are the nonpatriots, and you are the un-Americans, and you ought to be ashamed of yourselves.”

Robeson could not travel abroad until a 1958 US Supreme Court ruling, written by Justice William O. Douglas, overturned travel bans based solely on someone’s beliefs and associations. He made triumphant concert tours in England, Australia, and Russia and performed at a sold-out recital at Carnegie Hall in New York, but the eight years of persecution and enforced idleness had taken a tremendous toll. He suffered from debilitating depression and spent the last 15 years of his life in relative seclusion.

Contrasting Robeson and Du Bois

It is instructive to compare the status of Robeson with that of his contemporary, W. E. B. Du Bois (1868-1963), another black radical. Du Bois was the first African American to receive a PhD (in history) from Harvard. A founder of the NAACP in 1909, the long-time editor of its major publication, Crisis, and an early advocate of Pan-Africanism, Du Bois’s writings (including 18 books) challenged America’s ideas about race and helped lead the early crusade for civil rights.

By the 1940s, Du Bois, like Robeson, had become a fierce critic of US racism and imperialism. From 1949 to 1955 Du Bois headed the Council on African Affairs, an anticolonialist group with which Robeson was also affiliated. As the Cold War escalated, the US government increasingly harassed Du Bois for his left-wing activism and his attacks on US imperialism and European colonialism. In 1948, the NAACP, fearful of being identified with radicals, fired Du Bois. That year, like Robeson, he supported former Vice President Henry Wallace’s Progressive Party campaign for president. In 1949 Du Bois was chairman of the Peace Information Center in New York, which promoted the Stockholm Peace Petition to ban nuclear weapons, a movement that the US government characterized as communist-inspired. Du Bois and other officers of the center were indicted by a federal grand jury on a charge of failing to register as foreign agents. In 1950 Du Bois ran unsuccessfully for the US Senate on the left-wing American Labor Party ticket. In 1953 the US State Department revoked Du Bois’s passport, three years after Robeson suffered the same fate.

Increasingly disillusioned with the United States, Du Bois officially joined the Communist Party in 1961 at the height of the Cold War. That year, at the invitation of President Kwame Nkrumah, Du Bois, by then 93 years old, took up residence in Ghana to serve as director of the Encyclopedia Africana, a project that Du Bois had been working on for many years. After the United States refused to restore his passport, Du Bois renounced his American citizenship and became a citizen of Ghana.

Like Robeson, Du Bois was too politically isolated to play a role in the civil rights movement that emerged in the 1950s. By the time he died at age 95 on August 27, 1963 — the day before the March on Washington — it is likely that few at the march had heard of Du Bois, whose writings were mostly forgotten at the time.

Today, however, Du Bois is recognized as one of the monumental intellectual and political figures of the 20th century and certainly its most influential African-American thinker. In the half-century since his death, his reputation as a brilliant sociologist, historian, polemicist, novelist, and editor has been restored, his writings reprinted, his books (especially The Souls of Black Folk) a staple of university courses, and his life reported in several prize-winning biographies. As soon as his life and ideas were rediscovered in the late 1960s, Du Bois became a major influence among both academics and activists. His writings eventually had enormous influence on civil rights activists, on the emerging field of black studies, and on the growing understanding of the anticolonial views and independence movements among people in the world’s poor nations. In 1972 the University of Pennsylvania named a dormitory for its former faculty member; in 1975 Harvard established the W. E. B. Du Bois Institute for African and African American Research; in 1976 the site of the house where he grew up in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, was designated a National Historic Landmark; and in 1994 the University of Massachusetts at Amherst named its main library after Du Bois.

A Robeson Revival?

In the 1970s, Robeson’s admirers — boosted by the upsurge of black studies and black cultural projects, plus the waning of the Cold War — began to rehabilitate his reputation with various tributes, documentary films, books, concerts, exhibits, and a one-man play that Avery Brooks performed on Broadway and around the country (and which has been revived at the Ebony Repertory Theatre).

In his 1972 autobiography, I Never Had It Made, Jackie Robinson said he regretted his remarks about Robeson. “I have grown wiser and closer to the painful truth about America’s destructiveness,” Robinson acknowledged. “And I do have an increased respect for Paul Robeson, who sacrificed himself, his career, and the wealth and comfort he once enjoyed because, I believe, he was sincerely trying to help his people.”

That year, both Rutgers University and Pennsylvania State University established Paul Robeson Cultural Centers on their campuses. In 1977, Gil Noble wrote and directed The Tallest Tree in Our Forest, a 90-minute documentary about Robeson. Two years later, Sidney Poitier narrated a 30-minute film, Paul Robeson: Tribute to an Artist, that won an Academy Award for Documentary Short Subject. In 1991, the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission declared The Paul Robeson House in Philadelphia (where he lived the last decade of his life) a historical landmark, and it has since been designated a National Historical Site in the National Register. Public high schools in New York City, Chicago, and Philadelphia are named after Robeson.

In 1995, after five decades of exclusion, Robeson’s athletic achievements were finally recognized with his posthumous induction into the College Football Hall of Fame. In 1998, the centenary of his birth, Robeson was posthumously given a Lifetime Achievement Grammy Award, as well as a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. In 1999, PBS broadcast Paul Robeson: Here I Stand, directed by St. Clair Bourne — the third documentary about Robeson — as part of its American Masters series. In 2004, Robeson’s admirers persuaded the US Post Office to honor him with a postage stamp. Three years later, the prestigious Criterion Collection released a DVD box set of six of Robeson’s films — Body and Soul (1925), Borderline (1930), The Emperor Jones (1933), Sanders of the River (1935), Jericho (1937), and Proud Valley, plus “Native Land” (a 1942 documentary about civil liberties that Robeson narrated) and the 1979 documentary Paul Robeson: Tribute to an Artist.

These tributes and reclamation projects have certainly helped restore Robeson’s memory from the depths of obscurity he suffered in the last 15 years of his life. But he is hardly as well-known today as other larger-than-life public figures — like Babe Ruth, Judy Garland, Frank Sinatra, or even DuBois — whose fame he equaled or surpassed at the height of his career.

Few Americans under 60 have heard Robeson’s recordings, seen his films, or read anything about him. Most Americans today do not recognize Robeson’s name, much less know about his astonishing accomplishments.

Some of this may simply be due to the fact that Robeson was accomplished in so many arenas that he is hard to categorize. He made his mark in two of America’s most visible fields — sports and show business — but his claim as the most talented person of the 20th century also rests on his remarkable achievements in linguistics, law, opera, and other fields, in addition to his political activism. In a world that likes to pigeonhole people in specific boxes, Robeson defies easy labels. For example, when a panel of authors, editors, professors, and others selected 15 notables into the inaugural class of the New Jersey Hall of Fame in 2008, the inductees included Toni Morrison, Thomas Edison, Meryl Streep, Yogi Berra, Bill Bradley, Frank Sinatra, Albert Einstein, Harriet Tubman, Bruce Springsteen, and Vince Lombardi, but not Robeson. A museum spokesperson at the time explained that Robeson did not make the cut because he was nominated in too many categories and did not receive enough votes in any one of them. (Criticism of the omission, including an article in The New York Times, led the museum to include Robeson the next year.)

It may also be the case that much of Robeson’s artistic oeuvre does not resonate with modern audiences. Many of Robeson’s recordings are still available on CDs, but his classic singing style — whether performing operas, show tunes, or spirituals — may be too formal for today’s Americans to appreciate. His films, too, may seem too stylized or propagandistic to the contemporary eye. An audio version of Robeson’s Broadway performance in Othello is available online, but there’s no video of this remarkable actor in that classic Shakespeare play. And even if it was available, how many Americans would turn to YouTube to watch it?

Although Robeson’s life and career were destroyed by the Red Scare, he has inspired many artists, particularly African Americans, to use their talents and celebrity to promote social justice. He befriended and opened the path for many others — including activist artists like Harry Belafonte, Sidney Poitier, Ruby Dee, and Ossie Davis. More recent black superstars like Denzel Washington, Danny Glover, Laurence Fishburne, and Spike Lee have carried on Robeson’s legacy of commitment and conscience.

“All that Paul Robeson stood for had enormous impact on American and global history,” observed Belafonte. “The combination of his art, intellect and humanity was rarely paralleled. The cruelties visited upon him by the power of the State stands as a great blemish on the pages of American history.”

It would be heartening to believe that a sustained campaign could restore Robeson’s deserved place among the pantheon of greatest Americans. Surely there is sufficient drama in Robeson’s remarkable life to merit a television miniseries or a Hollywood biopic, like recent films about Jackie Robinson and Cesar Chavez. But it is more likely that while Robeson’s reputation and name recognition will gradually grow, he will remain a marginal figure, greatly admired by the relatively few Americans who understand his giant accomplishments and his remarkable courage, but otherwise eclipsed by one of the ugliest episodes in our country’s history, one of the lasting legacies of McCarthyism and the Cold War.

Thanks to the author for sending this to Portside.

Spread the word