For decades, the labor movement’s efforts to halt its long slide have been—to speak plainly—an utter failure. The U.S. has gone from having 35 percent of its workforce unionized in the 1950s to 20 percent in the 1980s to just 10 percent today.

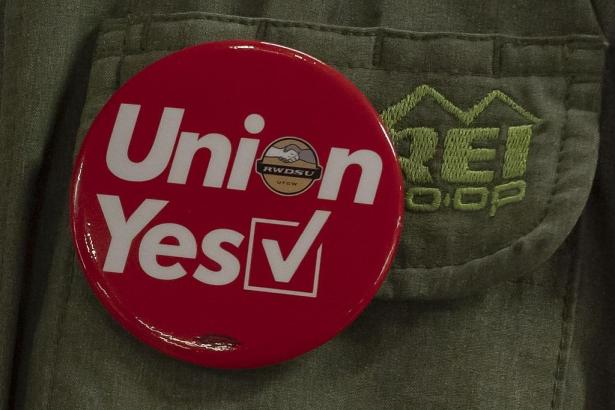

But now, finally, comes a burst of unexpected hope: lopsided union wins at more than 100 Starbucks across the nation, the landmark unionization victory at an Amazon warehouse on Staten Island, the first-ever unionization of an REI store, wins at two Google Fiber stores in Kansas City, a growing campaign to organize video game companies and Apple Stores, and undergraduate student workers at Grinnell voting 327 to 6 to unionize. And that’s the tip of the iceberg. This is exciting stuff. It reflects an overwhelming pro-labor sentiment among the young, 77 percent of whom approve of unions in the most recent Gallup poll. The same poll showed that among all Americans, 68 percent approve of unions, the highest level since the mid-1960s.

These numbers reflect broad public concern about the stratospheric levels of inequality that now define our economic life, about the emergence of a new generation of economic oligarchs, and about the decades of wage stagnation and economic insecurity that have dragged down tens of millions of Americans. Many Americans, most particularly the young, feel righteous anger about this cumulative assault on the prospect of broadly shared prosperity and a good and fulfilling life.

More from Steven Greenhouse | Harold Meyerson

All this anger and energy have created the possibility of a rebirth for American labor unions. The current wave of pro-union action could build into something far bigger, something that reverses labor’s decades-long decline.

But that requires something that has yet to happen: the all-out backing of the nation’s strangely quiescent union movement. Instead of pitching in, instead of rushing to help, most labor unions seem to be sitting on their hands as these young workers bravely seek to unionize. It makes you wonder what happened to the notion of solidarity.

IN MANY WAYS, this moment resembles a landmark moment in labor history. It was the mid-1930s, and workers in America’s mass-production industries were flexing their muscles and seeking to unionize. But the leaders of many craft-based unions in the American Federation of Labor had zero interest in helping these workers unionize. They looked down on mass-production workers as less skilled. They were also appalled by these workers’ efforts to organize all of a factory’s thousands of workers into one union, rather than dividing them by craft (and then slotting them into the appropriate craft unions). Most AFL unions turned their backs on this fledgling movement to unionize mass-production industries.

But John L. Lewis, then president of the United Mine Workers, the nation’s richest, most powerful union at the time, reacted very differently. Lewis could see that wall-to-wall unionization was the future, and along with several other union presidents (particularly Sidney Hillman of the Amalgamated Clothing Workers), he threw his weight behind this newfangled strategy.

Defying the AFL, Lewis decided to underwrite this movement of mass-production workers: autoworkers, steelworkers, and machinery workers. He hired more than 500 organizers to go to Detroit and Flint, to Johnstown and Akron, to Pittsburgh and Chicago, to organize the very factory workers his fellow union presidents had chosen to ignore. Thanks to Lewis’s foresight, the United Mine Workers’ very deep pockets, and the courage, solidarity, and organizing ingenuity of many mass-production workers, a modest trickle of unionization turned into a colossal wave. Union density among the nation’s nonagricultural workers nearly tripled, from 12 percent in 1935 to 32 percent in 1947.

One fear—or perhaps premonition—that drove Lewis was the idea that if the overall labor movement remained weak, that would inevitably erode the strength even of his own mighty Mine Workers. That same worry should weigh on today’s labor leaders. Unions can continue stumbling along with a sliver of the workforce, but labor leaders must ask how strong and effective their unions can remain in bargaining, in statehouses, and in Congress, if the percentage of workers in unions slips from 10 to 8 and then to 6 percent and below.

Lewis possessed the clarity of vision and sense of urgency to embrace the moment. His motto might have been: Damn labor’s inertia, full speed ahead.

That clarity and urgency are nowhere yet apparent among today’s labor leaders. But the opportunity to act is now squarely before them. Will they embrace the moment, or shrink from it?

BEGINNING THIS SUNDAY, the AFL-CIO will hold its first convention in five years (it was delayed for a year because of the pandemic). Barring a huge surprise, Liz Shuler, the federation’s well-liked president, will be elected to a full four-year term, after having succeeded Richard Trumka last August after he died of a heart attack. Several labor leaders told us that Shuler wants the nation’s unions to do considerably more to help today’s surge of unionization grow, but also that many unions in the federation feel little urge or compulsion to help.

As AFL-CIO president, Shuler doesn’t run the whole show. The federation works far more by consensus, with the biggest unions holding much of the power. According to labor leaders we spoke with, the three biggest unions in the AFL-CIO —the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees (AFSCME), the American Federation of Teachers (AFT), and the United Food and Commercial Workers (UFCW)—are saying all the right things, but haven’t yet stepped up to provide the money, lawyers, and other resources that are required to turn the current burst of unionization into a far larger, more lasting wave.

If not now, when? Not only is there a surge of youth-driven organizing in industries and companies that have not previously been organized, but Joe Biden is the most pro-union president in U.S. history, and his appointees at the National Labor Relations Board are enforcing workers’ legal protections more rigorously than they’ve been enforced during the past five decades. Moreover, millions of workers are angry about how poorly they were treated during the pandemic and are demanding better conditions at work. Today’s unusually low unemployment rate has emboldened millions more, as have the Black Lives Matter, #MeToo, and Fight for $15 movements.

This moment won’t last forever. A recession and higher unemployment may be just around the corner. Workers might soon start feeling less emboldened about sticking their necks out and unionizing.

And yet, organized labor remains mired in inertia. Most unions still do very little organizing. Last June, the Teamsters said they would launch a major effort to unionize Amazon’s warehouses, but a year later, there is little to show for it. (In fairness, the union’s new leadership has been in power for only two and a half months.) The unionization wave has been going strong for six months at Starbucks, but it hasn’t jumped to other fast-food companies like McDonald’s or Chipotle, where many workers complain of low wages. The UFCW seems to have all but given up seeking to unionize Walmart, Target, and many other major retailers.

Some unions, though, have been spending heavily on organizing. The Service Employees International Union (SEIU) underwrote the Fight for $15’s organizing efforts and has had huge success getting states to enact a $15 minimum wage, although it has failed to unionize any fast-food workers. The SEIU has also been organizing health care and airport workers, while its affiliate, Workers United, has been quietly backing the Starbucks organizing campaign with money and organizers. The Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union organized the REI store in Manhattan and, with many challenged ballots still to be counted, hopes yet to prevail in its drive to unionize an Amazon warehouse in Bessemer, Alabama. National Nurses United has been aggressively organizing nurses in several states, and the AFT has been organizing charter schoolteachers, college faculty, and grad student workers.

But there is vastly more to be done, and it’s time for organized labor to step up.

AS JON HIATT, the AFL-CIO’s former chief of staff and general counsel, has written for the Prospect, these unions and others should use this moment to form a “Coalition of the Willing” that creates a multimillion-dollar fund to help today’s surge of unionizing at Starbucks and other food and retail chains. They should feed and fuel these bottom-up, youth-driven, self-organizing efforts. This coalition should include not just AFL-CIO unions, but also unions outside the federation, like the SEIU, Teamsters, Carpenters, and National Education Association.

The labor movement has massive financial resources available to invest in this project, just as Lewis’s Mine Workers did in the 1930s. According to an in-depth analysis in Jacobin by Chris Bohner, who researches corporate finances for unions, America’s unions currently have $29 billion in net assets, of which $13.5 billion is in cash or cash equivalents. Some of that money is set aside for strike funds to support union members when they go on strike. But, as Bohner writes, “From 2010 to 2020, organized labor paid out on average $70 million a year in strike benefits, or just 0.35% of net assets annually.” To be sure, strikes have increased in number since 2018, but even prolonged large work stoppages would still leave plenty in the till to finance major organizing campaigns in retail and fast food, on campuses and elsewhere.

A key mission for the AFL-CIO and Coalition of the Willing should be to form a unified effort to organize Amazon. It would be far smarter to have one common campaign organizing a behemoth like Amazon than to have unions divided and fighting over jurisdictional lines. Christian Smalls, Derrick Palmer, and the Amazon Labor Union should of course play a major role in any unified Amazon effort, given their historic breakthrough in Staten Island and all they have to teach labor about bottom-up organizing at that company.

Many bottom-up unionization efforts seem ready to sprout at other companies, like Trader Joe’s, where workers at one store have filed for recognition for an independent union they’ve established. Such efforts badly need more money and resources, however. Established unions can provide that support, with the goal of maximizing union growth and worker power, while eschewing the old jurisdictional game of which union gets the members and dues money. Lewis and Hillman understood this when they formed the CIO to create new unions like the United Auto Workers and the United Steelworkers.

This ambitious organizing project, whether overseen by the AFL-CIO or the Coalition of the Willing, will need visionary individuals to oversee it, people with strong track records in organizing, like D. Taylor, president of UNITE HERE. It will need inspiring spokespersons—if you prefer, rabble-rousers—like Sara Nelson, president of the Association of Flight Attendants. (At the moment, Nelson is busy campaigning to unionize Delta’s flight attendants.) If unionists like Taylor and Nelson could lead these efforts, in conjunction with the heads of those unions that have actually been organizing, such as the SEIU’s Mary Kay Henry and the AFT’s Randi Weingarten, that could help ramp up organizing across the nation.

One simple thing that the AFL-CIO, and indeed all of the nations’ unions, could do is work to create an accessible online guide that explains how to organize your workplace and co-workers, while also explaining the rights and protections that workers have when they seek to unionize.

These unionization efforts will need plenty of lawyers, and together the nation’s unions should assemble a stable of attorneys who are ready to step in, for instance, when workers need help petitioning the NLRB to hold a unionization election or when workers believe they were illegally fired in retaliation for pushing to unionize.

FOR FAR TOO LONG, the nation’s labor movement has done far too little organizing, a stance that many union leaders defend by saying it’s too darn hard and expensive to win because the playing field is tilted against unions and in favor of corporations. That position has become harder to maintain as organizing drives by and for young workers have racked up one important win after another, often with overwhelming margins. And many other workers seem eager to ride this union wave.

Today’s labor leaders and labor unions have a crucial decision to make: Will they remain mere spectators to these efforts, thereby increasing the chances that this very promising moment will peter out? Or will they heed the example of John L. Lewis, and join in solidarity with the most pro-union generation this nation has seen in 80 years? Will they put up the money and resources required to turn this into a watershed moment for labor?

This is the first time in decades that America’s workers have a real opportunity to increase their power after it has steadily eroded for half a century. If organized labor fails to come in big to help, this may become the last time that workers have that opportunity.

Steven Greenhouse, a senior fellow at the Century Foundation, was a New York Times reporter for 31 years, including 19 as its labor and workplace reporter. He is the author of the book Beaten Down, Worked Up: The Past, Present, and Future of American Labor.

Harold Meyerson is editor at large of The American Prospect. His email is hmeyerson@prospect.org. Follow @HaroldMeyerson

Used with the permission. © The American Prospect, Prospect.org, 2022. All rights reserved.

The American Prospect is devoted to promoting informed discussion on public policy from a progressive perspective. In print and online, the Prospect brings a narrative, journalistic approach to complex issues, addressing the policy alternatives and the politics necessary to create good legislation. We help to dispel myths, challenge conventional wisdom, and expand the dialogue. Support the American Prospect Click here to support the Prospect's brand of independent impact journalism

Spread the word