Born out of oppressive conditions of the Black experience under white supremacy, the rich musical tradition of what is commonly known as “jazz” has a long and intimate relationship with the struggle for human and civil rights in the United States. However, the post-Second World War era saw a particularly militant and uncompromising form of musical expression parallel to the rising Black Power movement. Steeped in Black consciousness, internationalism, and anti-consumerism, free jazz or the “New Thing”—the most common name used among its practitioners at the time—represented a revolutionary segment of subaltern culture in the United States. Musicians strove to wrest control of their art away from a fundamentally racist and exploitative music industry. It was, to many, the sound of Black Power in the United States, music that showed its “teeth in a snarl rather than a smile.”1 Like the Black Power movement, which saw a blossoming of grassroots organizing to address the daily exclusion, exploitation, and oppression of Black communities, practical concerns of self-determination and collective autonomy were a central component of the music’s sociopolitical ethos.

The common social, political, and economic aims of artists associated with the New Thing were antithetical to the role jazz played in dominant narratives of U.S. freedom and equality, which were propagated in both civil society and the state. Both domestically and abroad, dominant narratives of the universality of jazz served to downplay the persistence of systemic racial inequality in the United States—a reality from which Black artists were not exempt. As Iain Anderson relates: “Although all musicians potentially faced exploitation, black artists experienced systematic abuse owing to their perceived lack of recourse against dishonest managers, lawyers, booking agents, and record companies. They were more liable than white musicians to be cheated of their composing and publishing royalties, shortchanged their percentage of gate receipts, and denied representation by the American Federation of Musicians.”2 Artists representing the New Thing were acting, in part, in response to these blatant disparities.

Divorcing the art form from this reality of racial oppression and longstanding racist assumptions concerning the perceived degeneracy of jazz culture among the country’s white population, the U.S. State Department propagated a Cold War narrative by parading select musicians around the world as proof of a “colorblind” American exceptionalism. Years later, the extent to which these tours provided cover for covert Central Intelligence Agency and military operations in the Global South would come to light.3 In stark contrast to such imperialistic appropriation, leading artists opposed to the Cold War weaponization of jazz connected their art and the fight from which it came with struggles for national liberation throughout the Global South. Saxophonist Archie Shepp famously stated that jazz “is anti-war, it is opposed to the U.S. involvement in Vietnam, it is for Cuba; it is for the liberation of all people. That is the nature of jazz. That’s not far-fetched. Why is that so? Because jazz is a music itself born out of oppression, born out of the enslavement of my people.”4 Shepp and his contemporaries sought to foster direct international connections, refute Cold War narratives of American exceptionalism, and testify that “Black music survived not because of capitalism but in spite of capitalism.”5 Toward this end, many participated in explicitly anticolonial international festivals, such as the Soviet-aligned 1962 World Festival of Youth and Students in Helsinki and the 1969 Pan-African Festival of Algiers. Such events were in direct opposition to the State Department-sponsored tours by the likes of noted Cold Warrior Dave Brubeck.

The antagonism between artistic exploration and the conservative standards of “the industry” necessitated greater autonomy from capitalist modes of production. Participants at all levels encouraged each other to “do it yourself, brother. Not brother can you spare 10 percent.”6 From the creation of artist-run independent record companies to the organizing of events and collectives geared toward promoting the interests of the artists, the New Thing represented a larger trend toward the democratization of subaltern cultural production.

Charles Mingus’s Counterfestival and the Jazz Artists Guild

The bassist and composer Charles Mingus was a longstanding proponent of such collective autonomy as well as a figure that undermined industry attempts at hyperclassification that have historically divided artists by using artificial consumerist barriers. Fed up with the “music business” and finding it harder to land recording dates, Mingus founded Debut Records in 1952 alongside drummer Max Roach—one of the most outspokenly militant modern jazz artists of the time. In stark contrast to the exploitative and highly unequal recording industry, each musician was given equal shares of sales, while the company took only 10 percent.7 According to historian Gerald Horne, it was also suggested that Mingus form “co-op clubs” with other musicians to challenge the dominance of club owners.8

In line with this desire for greater artist autonomy, Mingus organized a counterfestival in opposition to the highly commercialized Newport Jazz Festival in 1960. With an estimated six hundred people in attendance, The Newport Rebels Festival, as it would come to be known, included crossgenerational acts representing a wide variety of styles. Participants included swing legends, such as Coleman Hawkins, alongside leading figures on the cutting edge of the New Thing, such as Ornette Coleman and Eric Dolphy. Much like Mingus’s own compositions, the festival helped breakdown rigid categorization and the dominant dichotomy between tradition and innovation. Shunning the music industry, Mingus and the other musicians organized virtually every aspect of the festival themselves, from promotion and sales to construction of the stage and the conducting of ceremonies.9 As the cultural producers of the music, organizers worked to build power at odds with the exploitative jazz industry. The festival resulted in the creation of the Jazz Artists Guild by Mingus, Roach, and Jo Jones—an independent collective intended to produce music, promote concerts, and, most importantly, to give musicians more power over their music.10 Another highly influential endeavor Mingus took on was the creation of the Jazz Composers Workshop, which proved a space for musicians to develop their art away from the dictates of the market.

The October Revolution in Jazz

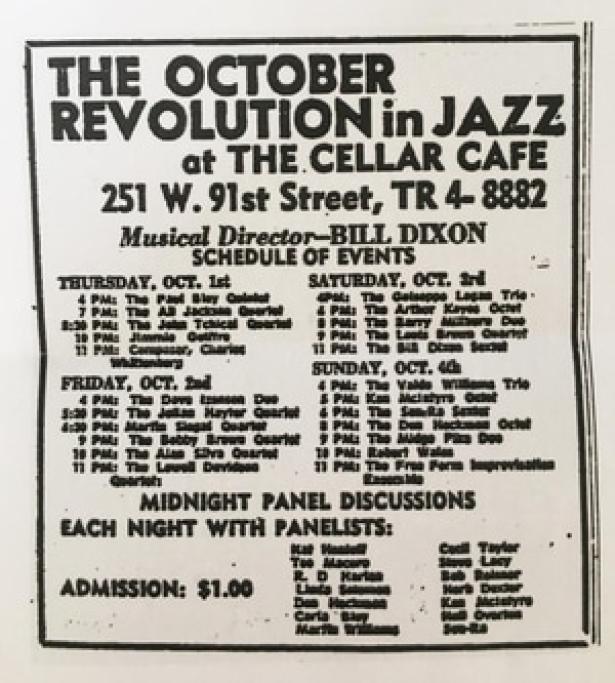

In 1964, trumpeter Bill Dixon and pianist Cecil Taylor organized a series of concerts held at the Cellar Cafe in New York City. Taking on the preparation for the concerts himself, Dixon contacted musicians, planned the schedule, and placed advertisements in local papers. Bringing together neglected or disenfranchised artists was a guiding principle of the event. As Dixon states, “I had one rule.… Anyone could play at the Cellar, as long as they weren’t playing any other place.”11 Billed as the October Revolution in Jazz, this four-day festival included some forty ensembles and solo performances, and was estimated to have had around seven hundred people in attendance. Performances went until midnight, at which time panels discussed various topics. Panel discussions included “Jim Crow and Crow Jim,” “The Economics of Jazz,” “The Rise of Folk Music and the Decline of Jazz,” and “Jazz Composition.”12 In his invaluable research, historian Benjamin Piekut found that

the discussion centered on issues of work and work privileges: the New York Musicians Union Local 802’s disregard for jazz musicians, the difficulty of landing a recording contract or playing date at one of the major clubs, the exclusion of African American musicians from the lucrative market of television music and commercial jingles, and the white monopoly of well-paying club dates in the Catskills and Broadway and off-Broadway shows. Jazz musicians of all colors were constantly having to negotiate unfavorable working conditions, but the panel conversations discussed the fact that black players were at an even larger disadvantage.13

The series fostered a greater desire for collective autonomy and provided a glimpse of how artists could organize their music apart from the highly commodified jazz industry. Much like the establishment of the Jazz Artists Guild in the wake of Mingus’s counterfestival, the Jazz Composers Guild grew out of the performances and discussions of the “October Revolution in Jazz” series. According to Dixon, the aim of the guild was “to establish the music to its rightful place in society; to awaken the musical conscience of the masses of people to that music which is essential to their lives; to protect musicians and composers from the existing forces of exploitation; to provide an opportunity for the audience to hear the music; to provide facilities for the proper creation, rehearsal, performance, and dissemination of the music.”14 The realization of such a vision necessitates that artists build an alternative to the parasitic capitalist relations of cultural production. Touching on the necessity of such alternative power, cofounding composer Taylor stated that they “had hoped to get together and try to make conditions that were more the way we felt would benefit the musicians and, like, not necessarily the gangsters that we usually have to deal with.”15 To foster a communal sense of self-respect among the musicians, guild members intended to withhold their labor from any job deemed unbeneficial to the guild as a whole.

Taylor points to racial tensions among members and “scabbing” of both white and Black musicians as key factors in the failure of the guild.16 Shepp in particular is often singled out for releasing Four for Trane with Impulse! Records without the consent of the collective. However, this record was made prior to the founding of the guild, and Impulse! already had contractual control. This highlights on the one hand the alienating and dispossessive nature of artistic production under capitalism and, on the other, the importance of alternative institutions such as artist-run record companies in struggles for artistic autonomy. More generally, if members who took jobs without the consent of the collective were, in fact, breaking a strike, then it seems fair to also assess the guild’s strike preparation—or lack thereof, as was the case with regard to strike funds to make withholding of labor feasible—and general inexperience as contributing factors in the guild’s demise.

There was also a significant range of political and social commitments among guild members with some taking more radical positions than others. In fact, Dixon was apparently the only member of the guild in favor of outright withdrawal of the music from the market.17 Therefore, structural fault lines, such as the failure to set up anything resembling a strike fund or to come to a group consensus on the withholding of labor, played a larger role than is suggested in much of the literature. The organizational obstacles introduced by sociopolitical heterogeneity within the group also included a wide range of commitments that were at times openly hostile toward clarifying what members such as Dixon saw as the social reality of the New Thing—that is, its historical significance under and against white supremacy.

While charges of individuals scabbing may fail to fully address structural shortcomings or the inherent difficulties in building alternative power in opposition to wealthy corporations, the well-documented racial tensions introduced by white members cannot be overstated and provide an important organizational lesson applicable well beyond the arts. Carla Bley points to the aversion of many white members toward addressing issues of racial inequality, which they considered irrelevant to a common struggle faced by all members. These members relied on language of common struggle not to build interracial solidarity, but to obscure the internal racial contradictions for the comfort of white members and the effective reproduction of the Cold War myth of colorblind jazz. Dismissive of the concerns and well-being of other members, Paul Bley says of guild meetings in his 1999 autobiography: “What a bunch of wounded souls there were at these meetings. Talk about group therapy. It was nothing for someone to stand up at a meeting and talk for two or three hours about the pain that they felt, the struggle—the inter-group, inter-race, inter-class, inter-family, inter-musical, inter-everything. The next night, the working nucleus of the guild would get together and do all the work.”18 In truth, such aversion to democratically addressing internal power dynamics was a significant impediment to group cohesion and a key factor in the guild’s eventual demise. Collectively, the guild failed to address internal contradictions around the insidious colorblind liberalism of white members, as well as those contradictions of a more organizational and strategic nature.

Jazz Press and the Reaction of White Civil Society

In addition to having to deal with white musicians who felt entitled to play jazz music without its social context, the New Thing came up against white reaction from the very industry against which it was rebelling. Relying on many of the same social mechanisms of coercion and delegitimization used in the defense of white supremacy more broadly, white critics often claimed the musicians’ desire to take their lives into their own hands and speak in their own voice with their own rich cultural history was a form of “reverse racism.” Persistent charges of “Crow Jim” (slang referring to perceived discrimination against whites) on the part of white critics obscured the structural nature of Jim Crow and other racist policies that codified systematic material deprivation and terrorization of Black people by equating anti-Black racism in the United States to Black people wanting to collectively organize and shape their own culture.

As participants, white musicians did face discrimination. However, such discrimination did not come from a systemic effort on the part of Black musicians that could be considered analogous to the systemic oppression of Jim Crow, but rather from the hiring practices dictated by a highly commodified and racialized industry. The fact that white artists to some degree shared in the economic hardship that came with participating in a Black and noncommercial art form is something to which none of the people who cried “Crow Jim” ever called attention. Instead, white people claimed musicians were discriminating against them, when the musicians were in fact responding to the systematic discrimination in the music industry. Those whites who wanted to play the music and respected the desires of its originators were welcome, and they struggled alongside their Black comrades against the music industry and the hegemony of Western musicality. The claim that “the white man has no civil rights when it comes to jazz” is far too absurd to be taken as anything other than a childish throwing up of one’s hands amid mere discussion around the racial context of the music.19

Furthermore, if the success of Harry Belafonte was proof enough that Black artists were not systemically excluded from other forms of music—as the author of an article in Time magazine asserted—then one would think the high esteem that white musicians such as Charlie Haden were afforded in the artistic circles in question would be enough to refute charges of “Crow Jim.” However, such charges were never meant to describe fairly and accurately race relations in the music industry. Rather, they were a particular manifestation of a common tactic of oppression that is so pervasive that it does not require the conscious intent or awareness of those who perform this function.

Much like claims of “white genocide,” the charge of “Crow Jim” was a reaction to a problem that did not exist. More precisely, it was the social reaction to Black Power under the guise of addressing fictional systemic discrimination against white musicians. While artists such as Taylor, Mingus, Shepp, and Coleman asserted that the music belonged to Black people, they still hired white musicians. Black musicians also acknowledged the economic hardship of white people who played free jazz while maintaining that the hardship of Black artists was far more pervasive, violent, and not simply on the basis of playing music deemed undesirable by the music industry.20 The fear of exclusion is a colonial fear of reprisal, an unfounded fear that the oppressed would be equally as cruel to their oppressors as their oppressors have been to them.

As a cultural expression of Black Power, the music of the New Thing and its practitioners faced the same mischaracterizations and demonization as the broader movement for Black self-determination. Walter Rodney spelled out the meaning and function of Black Power as well as the role of white reaction to it in maintaining racial oppression:

Black Power is a call to black peoples to throw off white domination and resume the handling of their own destinies. It means that blacks would enjoy power commensurate with their numbers in the world and in particular localities. Whenever an oppressed black man shouts for equality he is called a racist.… Imagine that! We are so inferior that if we demand equality of opportunity and power, that is outrageously racist! Black people who speak up for their rights must beware of this device of false accusations. It is intended to place you on the defensive and if possible embarrass you into silence.21

In addition to these charges of reverse racism or “Crow Jim,” which were led not by white musicians but white critics, publications like Downbeat viewed music through the lens of liberalism, dismissing the economic discrimination faced by innovative artists as the failure of the latter to understand “supply and demand.” Coverage often divorced artists deemed to represent “free jazz” or the “avant-garde” from their own musical tradition, and in some cases, pitted musicians against each other for the sake of scandal and sensationalism.22 In 1966, the magazine organized the “Point of Contact” debate. Participants included Shepp, Taylor, and Sonny Murray as representatives of the New Thing; Cannonball Adderley as a representative of the more conventional hard bop style; and Rahsaan Roland Kirk, who was involved in both “inside and outside styles.”23 Art D’Lugoff, a white club owner, participated in the debate as a representative of the “jazz industry.” Rather than passively accept the liberal economism that pervaded popular discourse or play into divisions being fostered among the participating artists, Taylor and Shepp criticized the booking practices of D’Lugoff and other club owners and denounced the racist structure of the music industry more generally. Shepp made clear that individuals like D’Lugoff were in fact merely functionaries of a larger structure of racial oppression, stating that “The club owners are only the lower echelon of a higher power structure which has never tolerated from Negroes the belief we have in ourselves that we are people, that we are men, that we are women, that we are human beings.” In making collective efforts toward greater self-determination and cultural autonomy, Shepp and other artists of the time did not request, but rather asserted their right to a basic human dignity.

Grounded in the lived reality of Black oppression and resistance, the New Thing contradicted the Cold War weaponization of jazz and challenged the racial prejudices of white listeners. The creation of structures of cultural production that were controlled by artists collectively in opposition to the highly exploitative and discriminatory “jazz industry” reflected a common desire for greater artist autonomy and improvement of conditions more generally. While efforts such as the Jazz Composers Guild would be short-lived, the legacy of Black cultural autonomy in the art form lives on to this day in the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM). Founded shortly after the guild in 1965, the AACM has the dual function of providing an organizational nucleus for the collective artistic exploration of “Great Black Music”—as AACM members prefer to call their music—and providing musical education to Chicago’s Black population. The AACM’s ongoing legacy flies in the face of the all-too-common dichotomy between groundbreaking art and community engagement.24 From Mingus to the Jazz Composers Guild and the AACM, Black cultural autonomy has been asserted and at times contested. Rather than belonging to the national myth of American exceptionalism, the history of such efforts and the art it produced belong to a larger international history of subaltern struggles in the field of cultural production.

Notes

- ↩ Walter Rodney, The Groundings with My Brothers (New York: Verso, 2019), 45–46.

- ↩ Iain Anderson, This Is Our Music: Free Jazz, the Sixties, and American Culture (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2007), 76.

- ↩ Penny M. Von Eschen, Satchmo Blows up the World: Jazz Ambassadors Play the Cold War (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2006).

- ↩ Archie Shepp quoted in Philippe Carles and Jean-Louis Comolli, Free Jazz/Black Power (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2015), 11.

- ↩ Archie Shepp interviewed by Taneli Viiahuhta in Free Jazz Communism: Archie Shepp-Bill Dixon Quartet at the Eighth World Festival of Youth and Students in Helsinki 1962 (Helsinki: Rab-Rab Press, 2022), 81.

- ↩ LeRoi Jones (Amiri Baraka), Black Music (New York: Akashic Books, 2010), 138.

- ↩ John F. Goodman, Mingus Speaks (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2013).

- ↩ Gerald Horne, Jazz and Justice: Racism and the Political Economy of the Music (New York: Monthly Review Press, 2019), 181. The great John Coltrane was also considering taking this route toward greater collective autonomy at the time of his death in 1967.

- ↩ Anderson, This Is Our Music.

- ↩ Anderson, This Is Our Music, 92; Ingrid Monson, Freedom Sounds: The Civil Rights Call Out to Jazz and Africa (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007).

- ↩ Quoted in Benjamin Piekut, Experimentalism Otherwise: The New York Avant-Garde and Its Limits (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011), 102.

- ↩ Bernard Gendron, “After the October Revolution: The Jazz Avant-Garde in New York, 1964–65” in Sound Commitments: Avant-garde Music and the Sixties, ed. Robert Adlington (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009), 212–213.

- ↩ Piekut, Experimentalism Otherwise, 104.

- ↩ Quoted in Robert Levin, “The Jazz Composers Guild: An Assertion of Dignity,” DownBeat 32, no. 10 (May 6, 1965): 17–18.

- ↩ Taylor quoted in A. B. Spellman, Four Lives in the Bebop Business (New York: Limelight Editions, 1994), 25.

- ↩ Spellman, Four Lives in the Bebop Business, 27.

- ↩ Piekut, Experimentalism Otherwise, 127.

- ↩ Paul Bley and David Lee, Stopping Time: Paul Bley and the Transformation of Jazz, 92.

- ↩ “Music: Crow Jim,” Time, October 19, 1962.

- ↩ Levin, “The Jazz Composers Guild.”

- ↩ Rodney, The Groundings with My Brothers, 50.

- ↩ Far from being a new dynamic in the 1960s, historian Robin D. G. Kelley points out in Thelonious Monk: The Life and Times of an American Original (Free Press, 2009) that a similar dichotomy abstracted the relationship between musical expressions a decade earlier when bebop was being distinguished from swing in popular discourse.

- ↩ Monson, Freedom Sounds, 266.

- ↩ Adequate treatment of the extensive literature on the AACM alone is worth far more attention than can be provided here. Furthermore, the in-depth firsthand historical analysis of George Lewis’s A Power Stronger Than Itself: The AACM and American Experimental Music (University of Chicago Press, 2008) alone can say far more than I ever could.

Christian Noakes is a worker and freelance writer. He received a Masters in Sociology from Georgia State University.

Dear Reader, Monthly Review made this and other articles available for free online to serve those unable to afford or access the print edition of Monthly Review. If you read the magazine online and can afford a print subscription, we hope you will consider purchasing one. Please visit the MR store for subscription options. Thank you very much. — Monthly Review Eds.

Spread the word