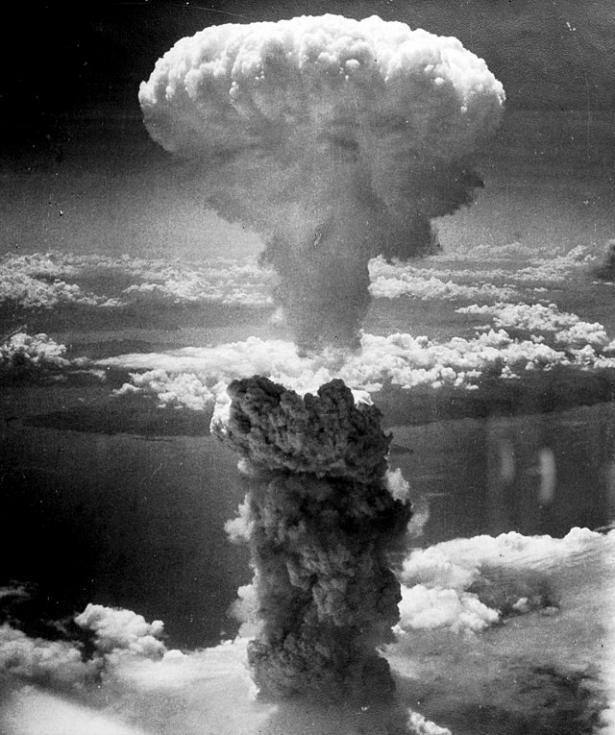

On August 6 and 9 throughout the world, people will commemorate the hundreds of thousands of Japanese people who died—crushed, vaporized, burned beyond recognition, poisoned by radiation—from the atomic bombs the United States dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945. The bombs’ hideous intent and impact constituted a crime against humanity, yet they were trivialized by the nicknames given them—“Little Boy” and “Fat Man.” The propaganda of their supposed necessity to end the war and save American lives was broadcast by our government and received by most Americans as truth.

Many top generals and admirals, more informed about Japan’s readiness to surrender than the American public, spoke forthrightly against their government’s use of the atomic bombs on both military and moral grounds, during and after the war. In a 1950 memo, Admiral William Leahy, White House chief of staff and chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff during the war, wrote, "the use of this barbarous weapon at Hiroshima and Nagasaki was of no material assistance in our war against Japan. The Japanese were already defeated and ready to surrender." Moreover, “in being the first to use it, we had adopted an ethical standard common to the barbarians of the Dark Ages."

Nor did all Pacific war veterans approve the atomic obliteration of the two civilian Japanese cities. In a 2001 interview, Ed Everts, a be-medalled major of the Army Air Corps who survived a crash at sea during the battle at Iwo Jima, stated that dropping of the atomic bombs was "a war crime" for which "our leaders should have been put on trial as were the German and Japanese leaders."

Two atomic bombs devised by our country in 1945 have proliferated to thousands today in nine countries, some more than 3,000 times as powerful as those dropped on Japan, many on trigger alert and able to be launched without time and clarity for humans to make a rational decision. Much vulnerability is baked into the nuclear weapons system: potential computer malfunction, imperfect information for decision-making, accident, cyber-attack, human error, and human imperfections like fatigue or drug abuse.

Intentionally killing civilians in war is a war crime but threatening and risking the existence of all life on this planet with nuclear weapons—ecocide—is the ultimate crime. Justifying these weapons of mass destruction as a deterrent to nuclear war—as the US and other nuclear weapons-owning governments do—is truly delusional. Despite the rhetoric of deterrence, we learned a few years ago that our government’s leaders have a set of fortified sites constructed to save themselves in the event of nuclear catastrophe, lest the deterrence factor fails, while the rest of us fend for ourselves. (See Raven Rock: The Story of the Government’s Secret Plan to Save itself While the Rest of US Die).

In its new cold war against China, the U.S. is locked in the domination fantasy that we must stay “top cop” in the world with no near competitors. This recent “great power” hostility is being used to justify our upgrading of nuclear weapons to more lethal, versatile and faster-delivery weapons of mass destruction.

While millions lost jobs and businesses suffered in 2020—victims of the Covid-induced economic crisis, the 2020 fiscal year was “good for the industry” according to a recent Defense News article. Their revenues worldwide were up about 5% from 2019, with US military industrial firms garnering the lion’s share. Upgrading nuclear weapons never slowed, assured by out-of-the-limelight government subsidies to the weapons’ industries during the Covid crisis.

Since 1946 the US has threated the use of nuclear weapons in conflict at least 12 times, according to security expert Joseph Gerson. But our time is running out. The “Doomsday Clock,” a visual representation of how susceptible the world is to a climate or nuclear catastrophe, registered '100 seconds to midnight' in both 2020 and 2021—the closest it has ever been to the symbolic extermination of humanity since it was conceived in 1947.

Our government should take a lesson from forests. In the past 25 years, scientists have discovered that trees in a forest communicate with each other, share nutrients and water, and act to protect neighboring trees from pests and other threats by releasing repelling chemicals. Given forests create microclimates, individual tree health depends on the forest community. Those trees connected in forests by underground life-supporting networks, christened the wood wide web, live far longer lives than isolated trees.

The takeaway lesson for hostile, competing nations: carefully craft rules of cooperation that trump hostility and the habit of weapons and war as a first resort. Like trees in their community of forests, humanity will live longer for sure.

[Pat Hynes, a retired professor of environmental health from Boston University School of Public Health, is a board member of the Trapock Center for Peace and Justice and member of the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom. Her forthcoming book, Hope But Demand Justice, will be published by Haley Publishers, Athol MA. ]

Spread the word