With the catastrophic recent term of the Supreme Court finally concluded, it can no longer be denied that the judiciary is firmly under the thumb of the conservative movement. In discussions of how the conservatives accomplished this feat, we often hear about the organizing acumen of the Federalist Society, or the vast financial resources of the Kochs, the Olins, and the Scaifes. But one critical ingredient has been largely overlooked, something the conservative movement has but its progressive counterpart does not: a compelling constitutional ideology.

This constitutional ideology—of which “originalism” is the most well-known offshoot—is an intellectual tool used by conservative judges to translate the political goals of the Republican Party into the language of judicial opinion. Law and politics are supposed to be different, so a judicial opinion cannot sound like a stump speech. Conservative constitutional ideology bridges the gap, translating Republican stump speeches into the supposedly apolitical language of jurisprudence, and supplying conservative judges with the rhetorical tropes and legal concepts they need to issue political decisions while maintaining a facade of legal reasoning.

For example, in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, Justice Alito did not say, “I am overturning Roe because I am pro-life.” He did not say, “I am overturning Roe because I am a Republican.” Instead, he said he was overturning Roe because the right to obtain an abortion does not “have a sound basis in precedent,” and because “regulation of abortion is not a sex-based classification and is thus not subject to the heightened scrutiny,” and because the Roe decision is not “rooted in our Nation’s history and tradition.” These snippets of impenetrable prose are simply the translation of the Republican Party’s platform into legalese. In making this translation, Alito and his fellow justices relied on legal concepts created by a decades-long project to invent and promulgate a new conservative legal ideology.

In addition to helping judges launder the Republican Party’s platform into judicial opinions, the conservative constitutional ideology serves a more subtle role as well. True believers in originalism see themselves as the sole inheritors of the “true” Constitution of the founding fathers. This messianic belief strengthens their will to power and motivates the conservative legal movement to adopt the hard-edged tactics that won it the judiciary. It gives the movement the self-confidence required to use the judiciary to impose its political vision on the rest of the country.

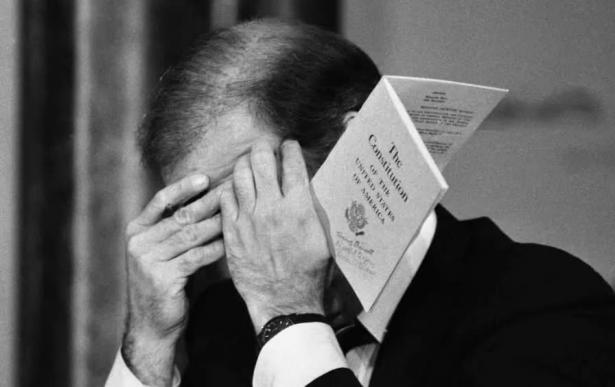

Compare this constitutional ideology with the current version of its liberal counterpart. Liberals, disciplined by decades of humiliating defeats in the courts, have entered into what Harvard Law professor Mark Tushnet has called a “defensive crouch,” narrowing their vision of what the Constitution stands for. Liberals drain their constitutional arguments of all moral or political substance, instead relying on technicalities and Latin phrases, hoping that by being scrupulously “neutral” they can shame conservatives into following suit. It should be no surprise that this strategy has failed.

Joseph Fishkin and William Forbath argue in their new book, The Anti-Oligarchy Constitution, that the Constitution is not “neutral.” To the contrary, they assert that the Constitution is best understood as embracing the unashamed struggle for equality—a legal concept, but one with political and economic significance. “We the People” can only be sovereign so long as economic as well as political power is broadly distributed. An oligarchic system in which economic—and therefore political—power is concentrated at the top is unconstitutional, Fishkin and Forbath contend, and they make their case with a wealth of historical evidence, from John Adams to Franklin Roosevelt. An egalitarian political program will only be possible, they insist, when liberals recover this egalitarian constitutional tradition and learn to make use of it.

Conservatives learned the importance of a compelling constitutional ideology the hard way. In 1968, Richard Nixon won the presidential election in part by promising to bring the liberal Supreme Court headed by Justice Earl Warren under conservative control. Even before winning office, he’d convinced Republican senators to launch the first-ever filibuster of a Supreme Court nominee, preventing President Lyndon Johnson from appointing a successor to Warren, who was looking to retire. And so, upon assuming office, Nixon already had an open seat on the court, to which he would appoint the conservative Warren Burger. To create a conservative majority, he then forced Justice Abe Fortas to resign through a series of characteristically dirty tricks. As his former White House counsel, John Dean, later noted, Nixon, the Department of Justice, and J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI orchestrated a string of politically motivated criminal investigations into Fortas, his wife, and his former law partner, eventually prompting the justice to resign. But even after conservatives controlled the court, Nixon and his administration discovered that this was not enough. Even with Burger in charge, there would be no conservative counterrevolution in the judiciary, at least not yet. The Burger court, after all, was the one that issued Roe v. Wade and enshrined constitutional rights for women, not the famously liberal Warren court.

What Nixon and the conservative justices discovered was that they may have controlled the court, but they were still, in many ways, prisoners of that era’s prevailing liberal legal ideology. Judges like to style their opinions as if they are simply explaining existing law: as if the outcome of any particular case flows from well-established legal principles without the need for the intervention of anything as sordid as human agency or—perish the thought!—politics. This self-presentation has been and remains the key to the judiciary’s power, but it also places a limitation on it. In order to maintain their pose as mere interpreters of the law, judges have to rigorously justify every proposition in their opinions with reference to the canon of legal authorities, a relatively small universe of past judicial opinions, books, and scholarly articles.

Therein lay the Burger court’s problem. It could not simply overrule the achievements of the Warren court, because it could not present such a move as an interpretation of existing law. To do so would have required a conservative constitutional ideology that was fully articulated in the canon of authorities and validated by the legal establishment. Without this, the Burger court had no choice but to leave the greatest achievements of the Warren court, for the most part, intact.

Conservatives soon learned the lesson of the Burger Court’s failure. If mainstream legal ideology did not get them the results they wanted, they would create a new one. As Steven Teles shows in his comprehensive study The Rise of the Conservative Legal Movement: The Battle for Control of the Law, conservative mega-donors were particularly enthusiastic about making this happen. Their method was simple: give money to law schools to hire conservative professors. These conservatives then used their newly won positions to write books and scholarly articles that translated the political goals of their movement into legal language—i.e., the kind of thing a conservative judge could cite in an opinion while still appearing legitimate. And thus emerged a new conservative ideology.

By far the most famous version of it is originalism, the idea that constitutional law should remain frozen and unchanging from the time of the founding fathers. Never mind that the founding fathers themselves were not originalists; they were all perfectly aware and supportive of the way constitutional law can change over time through the common law. But originalism offered modern conservatives the key to reshape the law to suit their own ends by translating their political goals into the supposedly apolitical language of jurisprudence.

Powered by this new ideology and supported by a new conservative-leaning legal establishment, the moderate Burger court gave way to the far more conservative Rehnquist court. The tone was set by Chief Justice William Rehnquist, the man who, as a lawyer in Nixon’s Department of Justice, was instrumental in the smearing of Abe Fortas. With Rehnquist at the helm, the Supreme Court began in earnest to dismantle the cherished liberal achievements of an earlier era—at first slowly and then faster and faster. The ascendance of the Roberts court in 2005 sped up the process even further. Now this ideology has become unquestionably and unapologetically dominant.

Which brings us to the other, more subtle role of originalism in the conservative legal movement. In addition to supplying judges with the intellectual tools required to issue conservative legal opinions, originalism provides the movement with enormous ideological self-confidence. In the movement’s imagination, it is the sole inheritor of the “true” law of the founding fathers, which has been corrupted by progressives like Woodrow Wilson and the liberals of the Warren Court. This allows the movement’s members to think of themselves as above mainstream lawyers and to sneeringly dismiss as “politics” any attempt to nudge constitutional law in the direction of greater equality.

Of course, there is nothing illegitimate about a constitutional jurisprudence that puts at its center the struggle for real equality. “Equality” is written into the Constitution and engraved on the facade of the Supreme Court. As Fishkin and Forbath also demonstrate, constitutional egalitarianism has a long history in the United States. From the country’s founding, the Constitution was understood by many to embody a principle of equality, based on the commonsense understanding that “We the People” cannot be truly sovereign so long as political and economic power remain concentrated in the hands of a narrow elite. As Fishkin and Fortbath point out, figures like John Adams and Noah Webster argued that popular sovereignty was impossible without broadly distributed economic power. They also demonstrate that even an “originalist” should understand the Constitution to embody a principle of genuine, if qualified, egalitarianism. Equality was part of the original intent of the law.

Fishkin and Forbath want liberals to recover this egalitarian constitutional tradition. An anti-oligarchy Constitution, they note, can be found throughout the 19th and 20th centuries. John Quincy Adams argued that the Constitution demanded that Congress pass policies designed to create a broad middle class. Abraham Lincoln understood the “liberty” promised by the Constitution to require economic independence and to be inconsistent with chattel slavery and a narrow concentration of capital.

Constitutional arguments of this sort were also advanced in the 1930s, as Franklin Roosevelt and his New Dealers sought to portray the expansive welfare state formed during the Depression and the Second World War as an expression of fundamental constitutional values. But for Fishkin and Forbath, liberals started to become complacent in the postwar years, just as conservatives started to become active. Liberals began to think of economics as a purely scientific and objective discipline, walled off from the world of politics, and they began to think of the Constitution in much the same way: as a technical puzzle, suitable only for experts, and not the proper subject of political debate.

To Fishkin and Forbath’s chagrin, this view of the law is still the dominant today. Many liberals think of the Constitution as something that can be expounded only in a courtroom. This way of thinking surrenders the fundamental statement of our nation’s principles to lawyers—a narrow, unrepresentative elite, protective of its social prestige and operating according to its own obscure norms and ethics. It should be no surprise, then, that today’s constitutional jurisprudence is conservative, hyper-technical, and obscurantist.

For Fishkin and Forbath, however, the meaning of the Constitution is too important to be left to the lawyers. Today’s liberals have to realize, as FDR did, that the “political equality” promised by the Constitution is “meaningless in the face of economic inequality.” Therefore, “a new constitutional political economy” is needed, one in which the Constitution is understood not just as a code of law for the courts but as a mission statement for all of the elected branches, guiding them in the enactment of policies designed to ensure that political and economic power are broadly distributed. Fishkin and Forbath suggest a broad slate of reforms—encompassing labor law, antitrust, and many others—which are similar in substance to many of the ideas percolating in the progressive circles of the Democratic Party. But Fishkin and Forbath’s innovation here is to argue that these policies should be justified in constitutional terms.

The authors spend most of the book exploring how the anti-oligarchy Constitution can be advanced by the elected branches of government, reasoning that the courts will eventually have no choice but to follow. This emphasis on political activism is undoubtedly correct, but we should not forget the importance of legal activism. Just as conservative scholars and judges encoded originalism into the canon of legal authorities, progressive scholars—such those associated with the Law and Political Economy Project—must do the same for the egalitarian constitutional tradition described by Fishkin and Forbath, exploring how these principles would apply to legal issues in the real world. Liberal lawyers, in turn, should present arguments based on this scholarship in favorable courts (vanishingly few though they may be at present) and create a body of persuasive precedent. As the success of the conservative legal movement has shown, this is how the law changes.

These novel legal ideas face an uphill climb. And they can only make that climb as part of a broader political and grassroots movement. Fishkin and Forbath recognize this, insisting that the “membrane” between constitutional litigation inside the court and political advocacy outside the court is “permeable.” But it will be in the streets as well as the courts that a new egalitarian politics will emerge—because, at the end of the day, it is the people, not the courts, who are the final arbiters of our country’s fundamental values.

Copyright c 2022 The Nation. Reprinted with permission. May not be reprinted without permission. Distributed by PARS International Corp.

Spread the word