The larger historical saga of Hollywood writers on the run from the FBI and Congressional hearings gets a small boost from time to time, then slips back into the memory hole of events and personalities, long ago. That history has special interest for this reviewer, who interviewed several dozen survivors, saw as many of the films the future Blacklist victims wrote as possible (something like 400) and tried to figure out, across several volumes, the meaning of it all. My collaborator Dave Wagner, a blacklist victim in the newspaper trade—guilty of leading a major strike in the late 1970s—understood the deeper personal part better than I could.

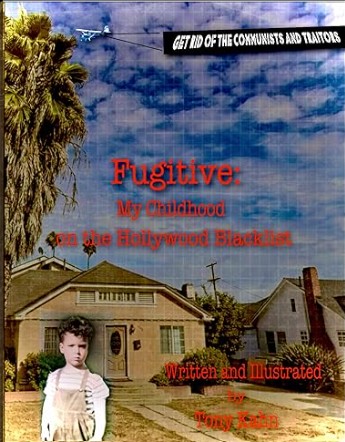

Fugitive: My Boyhood under the Hollywood Blacklist

by Tony Kahn

Self-Published by Author, Available from Amazon

Pages: 120

Paperback: $29.99; Kindle: $9.99

ASIN : B0D6CSWLX5

Fugitive also calls to mind a little-noticed book of last year: Flights: Radicals On the Run, by Joel Whitney. Here, nearly twenty writers’ sagas spread out in front of the reader, across several continents of artists and their pursuers (mainly, not only the FBI), Graham Greene and Lorraine Hansberry to Seymour Hersh and Malcolm X. The relentlessness of the authorities stands out, along with the massive budget obviously needed not only to pursue them but to feed the press with distortions and outright lies. The State is not our protector, far from it.

The most amazing part of Tony Kahn’s own story may be that more than a handful of the Hollywood victims had become spectacularly successful during Wartime, writing Oscar-winning films (my Republican parents’ favorite was “Woman of the Year,” because Katharine Hepburn won their hearts). Others made a living and seemed ready for better success ahead as films raced upward to their audience peak in 1946—and a very few years afterward. The rise of TV, of course, meant that film audiences would never be the same, although the rising prospects for film art, mainly from abroad, gave the more fortunate and prestigious victims like Joseph Losey a chance for decades of successful work.

What had been their winning themes in happier Hollywood years? Patriotic, anti-fascist crowd-boosters; revelations of democracy’s dark spots including racism and anti-semitism; also slapstick comedy, musicals and kids’ films. All of these continued until about 1950, when Congressional commttee subpoenas anticipated or followed trips from FBI agents and denunciations in the gossip columns.

During happier years, film work had been a good run for B film writers as well as the famous “swimming pool communists” who contributed heavily to leftwing causes. Writers in trouble could look back a few years to fundraising parties with Charlie Chaplin, Lucille Ball, Frederick March and naturally Katharine Hepburn among many others in the hills near the famed Hollywood sign.

Suddenly, it was all over. Tony Kahn’s father Gordon Kahn had his success mainly in “B” features, most notably the musical-and-action feature that brought Roy Rogers and Dale Evans together on the screen for the first time: The Cowboy and the Senorita (1944). A decade earlier, he made a “Script Contribution” to the first version of heavily antiwar All Quiet on the Western Front. But his Left politics got in the way….until wartime. Studio chiefs hated activists in the screenwriters’ union until they needed them, that is, after Pearl Harbor and the US entry into the War.

Things went great, seemed to go great in every possible genre, cowboy films (a couple of left-oriented Hopalong Cassidy features among them), witty adaptations of Broadway hits, slapstick comedy, heavily patriotic battle films, kids films, and after the war, just as heavily noir. Some were great cinematic art, within Hollywood limits, some were second-feature seat fillers. None of the pre-1950 films were taken off the screens after the screenwriters got the boot, although a large handful made in the next years never reached US theaters. They were as good as banned as soon as the writers became known.

The Kahn family, meanwhile, landed in Mexico in 1952, and Gordon Kahn wrote a wide variety of journalistic pieces under pseudonyms, while also trying to continue with films. Their little community of screenwriters gathered, found ready friends in the Mexican Left, lived inexpensively, and might even have enjoyed a sort of extended holiday exile. Except that more than a few, including the Kahns, took terrible advice, investing with a supposed Mexican ally who stole their savings, pretending to pay “dividends” until he had cleared out their accounts. The Kahns were broke and had to come back, with the FBI never far out of sight.

It is unclear why J. Edgar Hoover had a special interest in Gordon Kahn except that perhaps, as an editor of The Screenwriter during the 1940s, he played an important union role. His son provides documentation, with personal memos from Hoover, demonstrating great persecutory interest as the family travels back across the border, finally to relatives in New England. There, they struggle to make a living, face new redbaiting but manage to get along until the stress is too great. Gordon Kahn succumbed to a heart attack.

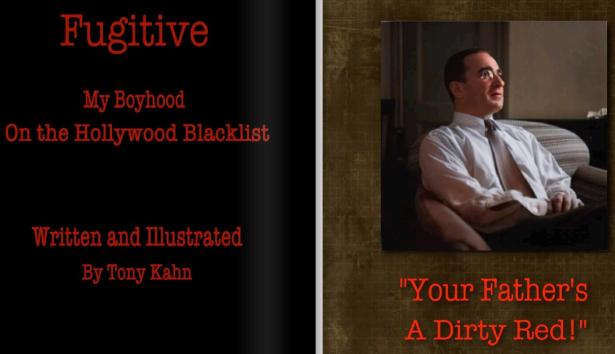

That author Tony Kahn would tell this story in “comic” form—actually an illustration form that combines photoshop techniques with dialogue boxes—offers the working of a highly creative mind. Many images feature himself as a kid, his father and the rest of his family, also newspaper clippings, personal letters, FBI memos and so on. Thus the side story of his brother Jim, ten years after father Gordon’s death, seeking a public health position but facing FBI officials who urge him to “clear” himself by denouncing his father (he refused).

If Fugitive, the Family Blacklist story, were to reach its logical end, Tony Kahn’s fellowship from getting a National Endowment for the Arts to develop a radio show around his family’s life, would have been broadcast and offer a kind of vindication. No such luck. Just at this time and by coincidence or not, Newt Gingrich denounced the National Public Radio programming in Congress. The fellowship suddenly disappearing without explanation: his payments stopped.

Who suddenly developed Cold Feet about an approved federal grant? No one knows, no one has blown the whistle and probably no one will ever find out.

This story does not end because Tony Kahn is too tough to be silent. His radio work, so highly praised by NPR, goes on.

On the film front, at the end of the 1990s, some of the Hollywood writers got back their credits for films written in the 1950s under pseudonyms or friendly “fronts.” The Screenwriters Guild, become the Writers’ Guild, issued an apology for blacklisting its own members forty-some years earlier, and several of the famous writers received public acclaim and apologies in 1999, the fiftieth anniversary of the Blacklist.

It was something, although surely not enough. The survivors of the Hollywood Blacklist are now all gone. If contemporary reports are accurate, writers and actors supporting the Palestinian cause face another generation of blacklisting. In one form or another, the story goes on.

[Paul Buhle, with Dave Wagner, wrote Radical Hollywood and Hide in Plain Sight, stories of the writers and their films from the early 1930s to the late 1970s.]

Spread the word