How to Turn a Nightmare into a Fairy Tale - 40 Years Later; The Forgotten Power of the Vietnam Protest, 1965-1975

- How to Turn a Nightmare into a Fairy Tale - 40 Years Later, Will the End Games in Iraq and Afghanistan Follow the Vietnam Playbook? -- Christian Appy (TomDispatch)

- The Forgotten Power of the Vietnam Protest, 1965-1975 - Tom Hayden (The Peace & Justice Resource Center)

By Christian Appy

April 26, 2015

TomDispatch

If our wars in the Greater Middle East ever end, it's a pretty safe bet that they will end badly -- and it won't be the first time. The "fall of Saigon" in 1975 was the quintessential bitter end to a war. Oddly enough, however, we've since found ways to reimagine that denouement which miraculously transformed a failed and brutal war of American aggression into a tragic humanitarian rescue mission. Our most popular Vietnam end-stories bury the long, ghastly history that preceded the "fall," while managing to absolve us of our primary responsibility for creating the disaster. Think of them as silver-lining tributes to good intentions and last-ditch heroism that may come in handy in the years ahead.

The trick, it turned out, was to separate the final act from the rest of the play. To be sure, the ending in Vietnam was not a happy one, at least not for many Americans and their South Vietnamese allies. This week we mark the 40th anniversary of those final days of the war. We will once again surely see the searing images of terrified refugees, desperate evacuations, and final defeat. But even that grim tale offers a lesson to those who will someday memorialize our present round of disastrous wars: toss out the historical background and you can recast any U.S. mission as a flawed but honorable, if not noble, effort by good-guy rescuers to save innocents from the rampaging forces of aggression. In the Vietnamese case, of course, the rescue was so incomplete and the defeat so total that many Americans concluded their country had "abandoned" its cause and "betrayed" its allies. By focusing on the gloomy conclusion, however, you could at least stop dwelling on the far more incriminating tale of the war's origins and expansion, and the ruthless way the U.S. waged it.

Here's another way to feel better about America's role in starting and fighting bad wars: make sure U.S. troops leave the stage for a decent interval before the final debacle. That way, in the last act, they can swoop back in with a new and less objectionable mission. Instead of once again waging brutal counterinsurgencies on behalf of despised governments, American troops can concentrate on a humanitarian effort most war-weary citizens and soldiers would welcome: evacuation and escape.

Phony Endings and Actual Ones

An American president announces an honorable end to our longest war. The last U.S. troops are headed for home. Media executives shut down their war zone bureaus. The faraway country where the war took place, once a synonym for slaughter, disappears from TV screens and public consciousness. Attention shifts to home-front scandals and sensations. So it was in the United States in 1973 and 1974, years when most Americans mistakenly believed that the Vietnam War was over.

n many ways, eerily enough, this could be a story from our own time. After all, a few years ago, we had reason to hope that our seemingly endless wars -- this time in distant Iraq and Afghanistan -- were finally over or soon would be. In December 2011, in front of U.S. troops at Fort Bragg, North Carolina, President Obama proclaimed an end to the American war in Iraq. "We're leaving behind a sovereign, stable, and self-reliant Iraq," he said proudly. "This is an extraordinary achievement." In a similar fashion, last December the president announced that in Afghanistan "the longest war in American history is coming to a responsible conclusion."

If only. Instead, warfare, strife, and suffering of every kind continue in both countries, while spreading across ever more of the Greater Middle East. American troops are still dying in Afghanistan and in Iraq the U.S. military is back, once again bombing and advising, this time against the Islamic State (or Daesh), an extremist spin-off from its predecessor al-Qaeda in Iraq, an organization that only came to life well after (and in reaction to) the U.S. invasion and occupation of that country. It now seems likely that the nightmare of war in Iraq and Afghanistan, which began decades ago, will simply drag on with no end in sight.

The Vietnam War, long as it was, did finally come to a decisive conclusion. When Vietnam screamed back into the headlines in early 1975, 14 North Vietnamese divisions were racing toward Saigon, virtually unopposed. Tens of thousands of South Vietnamese troops (shades of the Iraqi army in 2014) were stripping off their military uniforms, abandoning their American equipment, and fleeing. With the massive U.S. military presence gone, what had once been a brutal stalemate was now a rout, stunning evidence that "nation-building" by the U.S. military in South Vietnam had utterly failed (as it would in the twenty-first century in Iraq and Afghanistan).

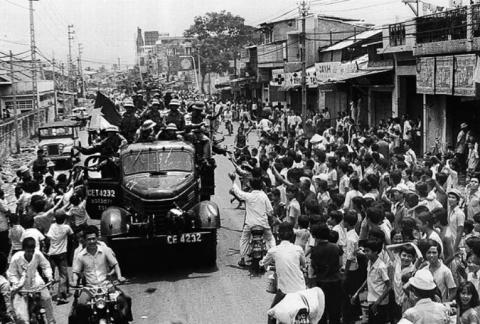

On April 30, 1975, a Communist tank crashed through the gates of Independence Palace in the southern capital of Saigon, a dramatic and triumphant conclusion to a 30-year-long Vietnamese struggle to achieve national independence and reunification. The blood-soaked American effort to construct a permanent non-Communist nation called South Vietnam ended in humiliating defeat.

It's hard now to imagine such a climactic conclusion in Iraq and Afghanistan. Unlike Vietnam, where the Communists successfully tapped a deep vein of nationalist and revolutionary fervor throughout the country, in neither Iraq nor Afghanistan has any faction, party, or government had such success or the kind of appeal that might lead it to gain full and uncontested control of the country. Yet in Iraq, there have at least been a series of mass evacuations and displacements reminiscent of the final days in Vietnam. In fact, the region, including Syria, is now engulfed in a refugee crisis of staggering proportions with millions seeking sanctuary across national boundaries and millions more homeless and displaced internally.

Last August, U.S. forces returned to Iraq (as in Vietnam four decades earlier) on the basis of a "humanitarian" mission. Some 40,000 Iraqis of the Yazidi sect, threatened with slaughter, had been stranded on Mount Sinjar in northern Iraq surrounded by Islamic State militants. While most of the Yazidi were, in fact, successfully evacuated by Kurdish fighters via ground trails, small groups were flown out on helicopters by the Iraqi military with U.S. help. When one of those choppers went down wounding many of its passengers but killing only the pilot, General Majid Ahmed Saadi, New York Times reporter Alissa Rubin, injured in the crash, praised his heroism. Before his death, he had told her that the evacuation missions were "the most important thing he had done in his life, the most significant thing he had done in his 35 years of flying."

In this way, a tortured history inconceivable without the American invasion of 2003 and almost a decade of excesses, including the torture and abuse at Abu Ghraib, as well as counterinsurgency warfare, finally produced a heroic tale of American humanitarian intervention to rescue victims of murderous extremists. The model for that kind of story had been well established in 1975.

Stripping the Fall of Saigon of Historical Context

Defeat in Vietnam might have been the occasion for a full-scale reckoning on the entire horrific war, but we preferred stories that sought to salvage some faith in American virtue amid the wreckage. For the most riveting recent example, we need look no further than Rory Kennedy's 2014 Academy Award-nominated documentary Last Days in Vietnam. The film focuses on a handful of Americans and a few Vietnamese who, in defiance of orders, helped expedite and expand a belated and inadequate evacuation of South Vietnamese who had hitched their lives to the American cause.

The film's cast of humanitarian heroes felt obligated to carry out their ad hoc rescue missions because the U.S. ambassador in Saigon, Graham Martin, refused to believe that defeat was inevitable. Whenever aides begged him to initiate an evacuation, he responded with comments like, "It's not so bleak. I won't have this negative talk." Only when North Vietnamese tanks reached the outskirts of Saigon did he order the grandiloquently titled Operation Frequent Wind -- the helicopter evacuation of the city -- to begin.

By that time, Army Captain Stuart Herrington and others like him had already led secret "black ops" missions to help South Vietnamese army officers and their families get aboard outgoing aircraft and ships. Prior to the official evacuation, the U.S. government explicitly forbade the evacuation of South Vietnamese military personnel who were under orders to remain in the country and continue fighting. But, as Herrington puts it in the film, "sometimes there's an issue not of legal and illegal, but right and wrong." Although the war itself failed to provide U.S. troops with a compelling moral cause, Last Days in Vietnam produces one. The film's heroic rescuers are willing to risk their careers for the just cause of evacuating their allies.

The drama and danger are amped up by the film's insistence that all Vietnamese linked to the Americans were in mortal peril. Several of the witnesses invoke the specter of a Communist "bloodbath," a staple of pro-war propaganda since the 1960s. (President Richard Nixon, for instance, once warned that the Communists would massacre civilians "by the millions" if the U.S. pulled out.) Herrington refers to the South Vietnamese officers he helped evacuate as "dead men walking." Another of the American rescuers, Paul Jacobs, used his Navy ship without authorization to escort dozens of South Vietnamese vessels, crammed with some 30,000 people, to the Philippines. Had he ordered the ships back to Vietnam, he claims in the film, the Communists "woulda killed `em all."

The Communist victors were certainly not merciful. They imprisoned hundreds of thousands of people in "re-education camps" and subjected them to brutal treatment. The predicted bloodbath, however, was a figment of the American imagination. No program of systematic execution of significant numbers of people who had collaborated with the Americans ever happened.

Following another script that first emerged in U.S. wartime propaganda, the film implies that South Vietnam was vehemently anti-communist. To illustrate, we are shown a map in which North Vietnamese red ink floods ever downward over an all-white South -- as if the war were a Communist invasion instead of a countrywide struggle that began in the South in opposition to an American-backed government.

Had the South been uniformly and fervently anti-Communist, the war might well have had a different outcome, but the Saigon regime was vulnerable primarily because many southern Vietnamese fought tooth and nail to defeat it and many others were unwilling to put their lives on the line to defend it. In truth, significant parts of the South had been "red" since the 1940s. The U.S. blocked reunification elections in 1956 exactly because it feared that southerners might vote in Communist leader Ho Chi Minh as president. Put another way, the U.S. betrayed the people of Vietnam and their right to self-determination not by pulling out of the country, but by going in.

Last Days in Vietnam may be the best silver-lining story of the fall of Saigon ever told, but it is by no means the first. Well before the end of April 1975, when crowds of terrified Vietnamese surrounded the U.S. embassy in Saigon begging for admission or trying to scale its fences, the media was on the lookout for feel-good stories that might take some of the sting out of the unremitting tableaus of fear and failure.

They thought they found just the thing in Operation Babylift. A month before ordering the final evacuation of Vietnam, Ambassador Martin approved an airlift of thousands of South Vietnamese orphans to the United States where they were to be adopted by Americans. Although he stubbornly refused to accept that the end was near, he hoped the sight of all those children embraced by their new American parents might move Congress to allocate additional funds to support the crumbling South Vietnamese government.

Commenting on Operation Babylift, pro-war political scientist Lucien Pye said, "We want to know we're still good, we're still decent." It did not go as planned. The first plane full of children and aid workers crashed and 138 of its passengers died. And while thousands of children did eventually make it to the U.S., a significant portion of them were not orphans. In war-ravaged South Vietnam some parents placed their children in orphanages for protection, fully intending to reclaim them in safer times. Critics claimed the operation was tantamount to kidnapping.

Nor did Operation Babylift move Congress to send additional aid, which was hardly surprising since virtually no one in the United States wanted to continue to fight the war. Indeed, the most prevalent emotion was stunned resignation. But there did remain a pervasive need to salvage some sense of national virtue as the house of cards collapsed and the story of those "babies," no matter how tarnished, nonetheless proved helpful in the process.

Putting the Fall of Saigon Back in Context

For most Vietnamese -- in the South as well as the North -- the end was not a time of fear and flight, but joy and relief. Finally, the much-reviled, American-backed government in Saigon had been overthrown and the country reunited. After three decades of turmoil and war, peace had come at last. The South was not united in accepting the Communist victory as an unambiguous "liberation," but there did remain broad and bitter revulsion over the wreckage the Americans had brought to their land.

Indeed, throughout the South and particularly in the countryside, most people viewed the Americans not as saviors but as destroyers. And with good reason. The U.S. military dropped four million tons of bombs on South Vietnam, the very land it claimed to be saving, making it by far the most bombed country in history. Much of that bombing was indiscriminate. Though policymakers blathered on about the necessity of "winning the hearts and minds" of the Vietnamese, the ruthlessness of their war-making drove many southerners into the arms of the Viet Cong, the local revolutionaries. It wasn't Communist hordes from the North that such Vietnamese feared, but the Americans and their South Vietnamese military allies.

The many refugees who fled Vietnam at war's end and after, ultimately a million or more of them, not only lost a war, they lost their home, and their traumatic experiences are not to be minimized. Yet we should also remember the suffering of the far greater number of South Vietnamese who were driven off their land by U.S. wartime policies. Because many southern peasants supported the Communist-led insurgency with food, shelter, intelligence, and recruits, the U.S. military decided that it had to deprive the Viet Cong of its rural base. What followed was a long series of forced relocations designed to remove peasants en masse from their lands and relocate them to places where they could more easily be controlled and indoctrinated.

The most conservative estimate of internal refugees created by such policies (with anodyne names like the "strategic hamlet program" or "Operation Cedar Falls") is 5 million, but the real figure may have been 10 million or more in a country of less than 20 million. Keep in mind that, in these years, the U.S. military listed "refugees generated" -- that is, Vietnamese purposely forced off their lands -- as a metric of "progress," a sign of declining support for the enemy.

Our vivid collective memories are of Vietnamese refugees fleeing their homeland at war's end. Gone is any broad awareness of how the U.S. burned down, plowed under, or bombed into oblivion thousands of Vietnamese villages, and herded survivors into refugee camps. The destroyed villages were then declared "free fire zones" where Americans claimed the right to kill anything that moved.

In 1967, Jim Soular was a flight chief on a gigantic Chinook helicopter. One of his main missions was the forced relocation of Vietnamese peasants. Here's the sort of memory that you won't find in Miss Saigon, Last Days in Vietnam, or much of anything else that purports to let us know about the war that ended in 1975. This is not the sort of thing you're likely to see much of this week in any 40th anniversary media musings.

"On one mission where we were depopulating a village we packed about sixty people into my Chinook. They'd never been near this kind of machine and were really scared but they had people forcing them in with M-16s. Even at that time I felt within myself that the forced dislocation of these people was a real tragedy. I never flew refugees back in. It was always out. Quite often they would find their own way back into those free-fire zones. We didn't understand that their ancestors were buried there, that it was very important to their culture and religion to be with their ancestors. They had no say in what was happening. I could see the terror in their faces. They were defecating and urinating and completely freaked out. It was horrible. Everything I'd been raised to believe in was contrary to what I saw in Vietnam. We might have learned so much from them instead of learning nothing and doing so much damage."

What Will We Forget If Baghdad "Falls"?

The time may come, if it hasn't already, when many of us will forget, Vietnam-style, that our leaders sent us to war in Iraq falsely claiming that Saddam Hussein possessed weapons of mass destruction he intended to use against us; that he had a "sinister nexus" with the al-Qaeda terrorists who attacked on 9/11; that the war would essentially pay for itself; that it would be over in "weeks rather than months"; that the Iraqis would greet us as liberators; or that we would build an Iraqi democracy that would be a model for the entire region. And will we also forget that in the process nearly 4,500 Americans were killed along with perhaps 500,000 Iraqis, that millions of Iraqis were displaced from their homes into internal exile or forced from the country itself, and that by almost every measure civil society has failed to return to pre-war levels of stability and security?

The picture is no less grim in Afghanistan. What silver linings can possibly emerge from our endless wars? If history is any guide, I'm sure we'll think of something.

[Christian Appy, TomDispatch regular and professor of history at the University of Massachusetts, is the author of three books about the Vietnam War, including the just-published American Reckoning: The Vietnam War and Our National Identity (Viking).]

Follow TomDispatch on Twitter and join us on Facebook. Check out the newest Dispatch Book, Nick Turse's Tomorrow's Battlefield: U.S. Proxy Wars and Secret Ops in Africa, and Tom Engelhardt's latest book, Shadow Government: Surveillance, Secret Wars, and a Global Security State in a Single-Superpower World.

Copyright 2015 Christian Appy. Reprinted with permission. May not be reprinted without permission from TomDispatch.

The Forgotten Power of the Vietnam Protest, 1965-1975

By Tom Hayden

April 27, 2015

The Peace & Justice Resource Center

With the U.S. Capitol in the background, demonstrators march along Pennsylvania Avenue in an anti-Vietnam War protest in Washington, on Moratorium Day, Nov. 15, 1969.

Credit: AP Photo // HowStuffWorks

Submitted to the conference on the "Vietnam War Then and Now, Assessing the Critical Lessons"

NYU Center, Washington DC, April 29-May 1, 1975

The era of protest against Vietnam - 1965-75 - was unique as the emergence of a nationwide peace movement on a scale not seen before in American history. There were previous war resisters, for example, the Society of Friends, the opponents of the Mexican War and the Indian wars, critics of the imperial taking of Cuba, Puerto Rico and the Philippines, and opponents of World War I, numbering in the many thousands. But no peace movement was as large-scale, long lasting, intense, and threatening to the status quo as the protests against the Vietnam War.

The roots of the Vietnam peace movement were in the civil rights, student, and women's movements of the early Sixties. The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, the Students for a Democratic Society, the Free Speech Movement and the National Organization for Women all were asserting domestic demands just as the US draft and troop escalation took place in 1965. SNCC's Mississippi Summer Project and Freedom Democrats' convention challenge occurred at the time of the August 1964 Tonkin Gulf "incident" and war authorization. SDS supported "part of the way" with LBJ in late 1964 while planning the first peace march in April 1965 in case Johnson broke his pledge of no ground troops. The Free Speech Movement of September 1964 set the stage for the Vietnam Day Committee and Berkeley's first teach-in. The civil rights movement and also Women's Strike inspired the National Organization of Women for Peace, which opposed Strontium-90 and pushed for President Kennedy's 1963 arms treaty with the Soviet Union. Together these movements were demanding a shift from Cold War priorities to "jobs and justice", the banner of the 1963 March on Washington, and were deeply shocked by the assassination of Kennedy and subsequent escalation in Vietnam.

During the Vietnam peace movement era between 1965-1975, Americans took to the streets in numbers exceeding one hundred thousand on at least a dozen occasions, sometimes half-million. At least 29 young Americans were murdered while protesting the war. Tens of thousands were arrested. The greatest student strikes in American history shut down campuses for weeks. Black people rose in hundreds of "urban rebellions" partly against the shift from the War on Poverty to the Vietnam War. GIs rebelled on scores of bases and ships, refused orders, threw their medals at the Congress, and often attacked their superior officers, prompting warnings about the "collapse" of the armed forces by the Seventies. Peace candidates appeared in Congressional races by 1966 and became a serious presence in presidential politics by 1968. President Lyndon B. Johnson was forced to resign because of a revolt within his own party in 1968, and Richard Nixon resigned after escalating a secret war and unleashing spies and provocateurs against dissenters at home.

The 1965-75 peace movement reached a scale which threatened the foundations of the American social order, making it an inspirational model for future social movements and a nightmare which elites ever since have hoped to wipe from memory. It's far simpler, after all, to incorporate into the American Story a chapter about a social movement overcoming discrimination than the saga of a failed war in which tens of thousands of Americans died while killing others.

The events of those ten years (1965-75) can be compared to the "general strike" - or non-cooperation - of the slaves on southern plantations that undermined the Confederacy, according to the classic study by W. E. B. Dubois, Black Reconstruction. Dubois wrote that, "The slave entered upon a general strike against slavery by the same methods that he had used during the period of the fugitive slave. He ran away to the first place of safety and offered his services to the Federal Army...and so it was true that this withdrawal and bestowal of his labor decided the war."[1]

In the case of Vietnam, the Vietnamese peasantry demanding land reform were the equivalent of the African slaves who resisted slavery and demanded "40 acres and a mule" the century before. The fundamental role of the Vietnamese resistance to the French and American occupiers will be discussed below. But their resistance awakened and triggered the eventual "general strike" in America that paralyzed campuses, cities, and barracks, forced a realignment to American politics, and brought the war to its end.

The first strand of the American resistance began in campus communities. Starting with polite dissent and educational teach-ins, by 1969-1970 there was a wave of student strikes that shuttered hundreds of campuses, involved four million in protests[2] and forced closures of those key institutions through the spring semester in 1970. Second, at the same time, 1964-71, there were seven hundred "civil disturbances" with more than one hundred deaths in Watts, Newark, and Detroit alone. Those "riots" were in protest against budgets that favored war spending over social programs, and they included many returning Vietnam veterans or their family members at home. Third, there came a GI revolt that included over 500 fraggings of officers in 1969-70, scores of "riots" on military bases, forty thousand desertions to Canada and Sweden, and official reports that the army was "approaching collapse."[3]"From 1970 on, the fight against the war was moving from the campus to the barracks,"[4] wrote one historian.

Amidst this general collapse, the peace movement was able to generate a political constituency that attracted peace candidates who threatened the Cold War consensus. The political revolt began in 1966 with the Robert Scheer and Stanley Sheinbaum candidacies in Democratic primaries, and grew into the national campaigns of Eugene McCarthy and Robert Kennedy in 1968 and George McGovern in 1972. The McCarthy campaign was driven almost entirely by student volunteers who later created the Vietnam moratoriums. The military draft was ended by January 1973 as, "an effective political weapon against the burgeoning antiwar movement."[5] A possible victory for peace was denied when Robert Kennedy was assassinated in June 1968 shortly after the killing of Martin Luther King Jr. By 1972, the Democratic Party had adopted a platform calling for complete and immediate withdrawal from Vietnam. American politics would be changed for decades by the Vietnam generation, much as the Abolitionists and Radical Republicans were allies of the Underground Railroad and the "general strike" in which slaves turned the tide of war. The deaths of King and the Kennedys, like the murder of Lincoln, undermined the transformative possibilities of a Second Reconstruction.

A cautionary conceptual note: thus "general strike" was not in any sense a planned or coordinated campaign, nor one led by radical vanguards. Rather, it was a continuous series of populist reactions that took place because of a vacuum of leadership by mainstream institutions. Activist peace and justice groups gave inspiration and support to this Great Refusal to conform, but massive desperation was the motor force. The alternative was submission, and that was not the character of the times.

The general strike forced a systemic crisis, "As deep as the civil war (and caused a prediction that) the very survival of the nation will be threatened," according to the Scranton Commission appointed by President Nixon after Kent State. It was a, "Crisis as deep as the civil war (and) the very survival of the nation will be threatened," in the words of the 1970 Scranton Commission. The crisis threatened the very stability of the economic system too; as early as 1967, "New York's financial community and the interests it represented were seriously worried about the war."[6] Business executives for peace started placing full-page ads in the New York Times that year.

There was no light at either end of the tunnel, from Berkeley to Saigon. The great rethinking was symbolized by the private consultations held between the president and a select group of business and military "wise men", who at first backed the war but reversed themselves in a March 1968 White House discussion, shocking Johnson with their advice to cut his losses and disengage. The war and the growing crisis at home had split the unity of the Cold War establishment, revealed most sharply in the Watergate crisis where Nixon chose to circumvent the Constitution in order to prolong the war. It was in this context that the hawkish ex-Marine Daniel Ellsberg chose to release the secret Pentagon Papers and face treason charges. His co-conspirator, Anthony Russo, was changed by face-to-face interrogations with Vietcong detainees, whom he came to respect. (Their action was the model for recent whistleblowers like Julian Assange and Edward Snowden.)

When the new doves in the ruling institutions began to demand disengagement, their views converged with the more radical demands of the anti-war movement to erode all remaining support for the Vietnam policy. The pillars of the Vietnam policy had been undermined by people power. The democratic process had prevailed over the "cancer on the presidency," as John Dean described the Watergate scandal. In the eyes of many establishment figures who originally endorsed the war, it had become unwinnable, unaffordable, and a threat to domestic tranquility.

Instead of blurry images of chaos, the peace movement should be seen as a shaving unfolded with an inner logic: at first, from the margins of society among young people who could be drafted but could not vote; from the inner cities where they were drafted in great numbers; from the poets and intellectuals; and finally spreading into mainstream sectors considered centrist. The trajectory was rapid, from 1964 to 1967. The peace constituency was large enough to polarize American politics, with the Democratic Party realigning between 1966 and 1968. The counter-movement was severe, ranging from police repression, to Nixon's "dirty tricks" campaign, to false promises of peace to sway voters, and finally to the withdrawal of US ground troops combined with an invisible air war. The war ended nonetheless, both on the battlefield with the fall of Saigon, and the fall of Nixon at Watergate.

A second observation about the Vietnam peace movement is that it was so divided - a movement of movements, which it was impossible to cohere into a unified national force like the AFL-CIO or NAACP. There were internal divisions along the lines of class, race, and gender; civilian resisters and rebels within the military; street protestors and politicians; advocates of nonviolence, electoral politics, disruption, and resistance. These different factions often quarreled bitterly, some at the instigation of the FBI but also due to ego sectarian and ideological rivalries. But in the end they interacted in cumulative ways that brought the war to an end, and with it the various internal movements themselves. For example, the students pushed their professors to call teach-ins, considered a moderate alternative to campus strikes, but which reached a much larger base of fence sitters. Similarly, the growing street resistance encouraged political leaders like McCarthy and RFK to define their campaigns as alternatives to the radical outside confrontations (even using phrases like "Clean for Gene" to distinguish themselves from the hippies.) In the end, as argued above, moderate sectors of the establishment joined with the moderate wing of the movement to disengage from Vietnam in order to save the American system as a whole.[7]

The tragedy of the anti-war movement is that the whole never lasted as greater than its parts. It might have been unified from 1968 onward if Martin Luther King had lived, Robert Kennedy was elected president, and the war terminated in 1969. That possibility was destroyed by their assassinations, leaving a disoriented, scarred and scattered generation of "might-have-beens." When the war did end in 1975, many of its opponents already had drifted away, moved on with their lives, or taken up more promising agendas. The peace movement had exhausted its historic role. So fractious were its groupings that there never was a reunion or convention to explore its meaning.

Read full paper here.

[1] Dubois, "The General Strike", https://facultystaff.richmond.edu/=aholton/121readings_html/generalstrike.htm

[2] Kirkpatrick Sale, SDS, p. 636. Sale says that 536 schools were, "Shut down completely for some period of time," 51 of them for the entire year.

[3] Lawrence Baskir and William Strauss, "Chance and Circumstance: The Draft, The War and the Vietnam Generation," Vintage Books, 1978.

[4] Jonathan Neale, A People's History of the Vietnam War", The New Press, p. 163, 2001.

[5] Andrew Glass, in Politico, January 27, 2012

[6] Powers, p. 197

[7] See the diagrams of these dynamics in The Long Sixties, especially the chapter on "Movements against Machiavellians", Paradigm, 2009.

[After over 50 years of activism, politics and writing, Tom Hayden is still a leading voice for ending the wars in Afghanistan, Iraq and Pakistan, for erasing sweatshops, saving the environment, and reforming politics through a more participatory democracy. He was a leader of the student, civil rights, peace and environmental movements of the 1960s, and went on to serve 18 years in the California legislature, where he chaired labor, higher education and natural resources committees.

In addition to being a member of the editorial board and a columnist for The Nation magazine, Hayden is regularly published in the New York Times, Guardian, Los Angeles Times, San Francisco Chronicle, Boston Globe, Denver Post, Harvard International Review, Chronicle of Higher Education, Huffington Post and other weekly alternatives. As Director of the Peace and Justice Resource Center in Culver City, California, he organizes, travels and speaks constantly against the current wars. He also recently drafted and lobbied successfully for Los Angeles and San Francisco ordinances to end all taxpayer subsidies for sweatshops.

The author and editor of twenty books, including the recently published "Inspiring Participatory Democracy: Student Movements from Port Huron to Today," Hayden describes himself as "an archeological dig." He has taught most recently at UCLA, Scripps College, Pitzer College, Occidental College, and the Harvard Institute of Politics.]

Spread the word