By all rights, Ruby Sales should have been killed on Friday, Aug. 20, 1965.

She should have been hit by the shotgun blast fired by the enraged white man on the porch of the general store in rural Alabama.

Her life should have ended at 17, an African American college student and civil rights worker, gunned down under a Coca-Cola sign in the fight for freedom and justice.

But there she was Sunday morning, age 67, in St. Alban's Episcopal Church in Northwest Washington, given a half-century of life by a white seminarian named Jonathan Myrick Daniels who pushed her aside and died in her place.

She sat in an ornate wooden chair in the chancel of the church, the decades having taken a toll on her eyesight and her knees, and called herself "a remnant" of the great civil rights generation now passing from the stage.

She spoke of the Saturday death of her friend and civil rights elder Julian Bond. She gave thanks for him, and for Daniels, who "in the twinkle of an eye" 50 years ago this week exchanged his white, privileged life for that of a precocious black teenager.

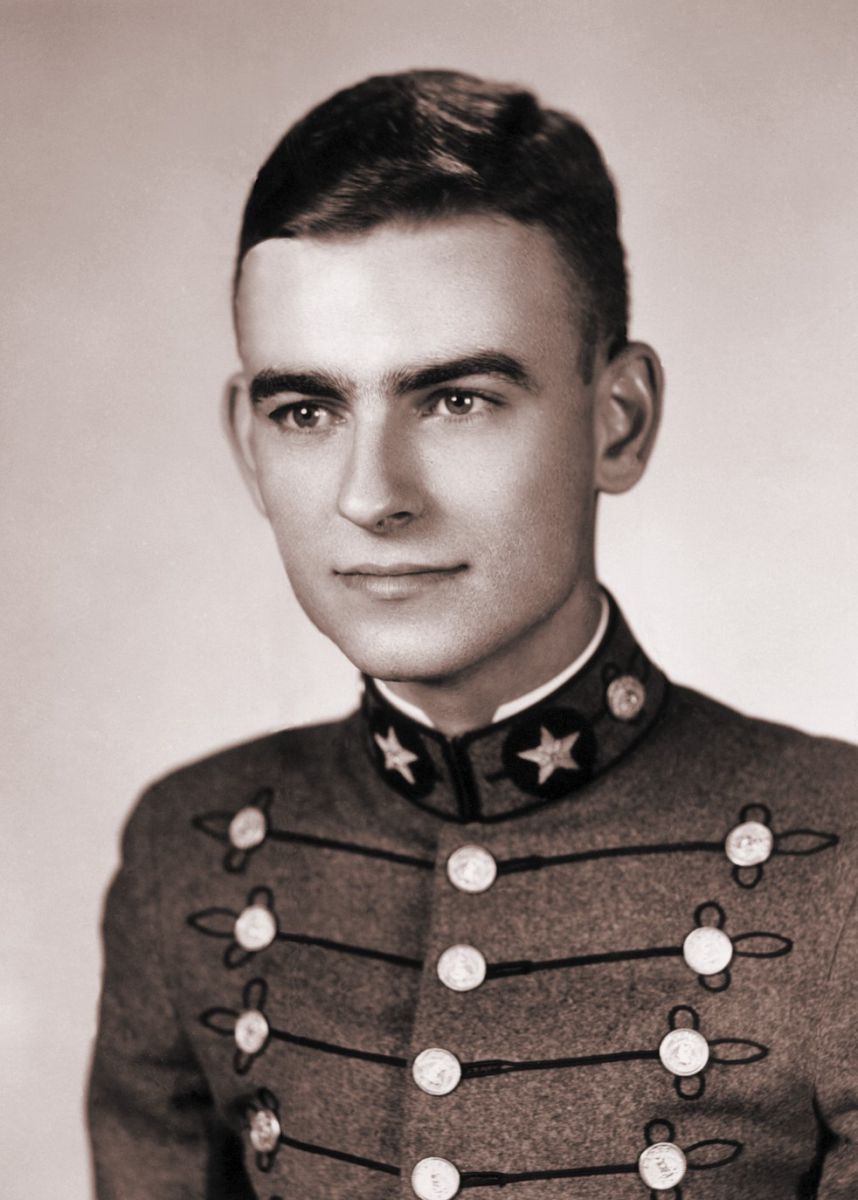

A close-up view of the new addition to the Hall of Heroes, Jonathan Myrick Daniels, at the National Cathedral in Washington.

credit: Bill O'Leary/The Washington Post

"It is a sweet moment to remember, even in the midst of sadness," she told the congregation gathered under the dark wooden beams of the venerable church to worship and hear her preach.

"Thanks be to God," she said.

But she also said that it was deeply troubling that the same hate that killed Daniels in 1965 "is as alive and virulent today as it was then ...50 years after Jonathan's death, my soul cannot rest."

Much has been written about Daniels, the 26-year-old Episcopal seminarian from New Hampshire who was killed that hot afternoon in Hayneville, Ala.

Although now largely forgotten, his slaying was front-page news across a country, then as today, torn by racial violence and upheaval, and was the latest in a string of brutal attacks on civil rights workers in the South.

Jonathan M. Daniels, a native of Keene, N.H., was valedictorian of the VMI Class of 1961.

Photo by VMI // Washington Post

Thomas L. Coleman, 55, a road construction supervisor and part-time deputy sheriff, was arrested in connection with Daniels's death. Coleman claimed he had fired in self-defense. He was acquitted before a white judge, by an all-white jury.

Since then, Daniels's name has been added to the Episcopal calendar, with an Aug. 14 feast day. A Daniels memorial has been erected in Hayneville. And a limestone sculpture of Daniels has just been created inside the Washington National Cathedral.

Ceremonies to mark the 50th anniversary of his slaying are set this week in his home town, Keene, N.H.

But less has been said about Sales, who for 50 years has lived with the nightmare of the killing, and the legacy of Daniels and others who fought on the civil rights battlefields of the 1960s.

For a time, she withdrew into herself and told no one what she had witnessed. She said she still has flashbacks.

"I didn't rob him of his life," she said in interviews from her home last month. "Racism did. And so what I've thought about is: Isn't it an absolute travesty that the society would kill its best and brightest when they stand up for freedom?"

Sales, who lived in Washington for many years, now resides in Atlanta, where she heads the SpiritHouse Project, a program that uses the arts, education and spirituality to bring about racial, economic and social justice, according to its Web site.

She is a former college professor who has taught at the University of Maryland and Spelman College in Atlanta and is an advocate for civil and welfare rights, women's rights, and lesbian and gay rights.

"I often imagine what would Jonathan be doing today," she said. "Would he have participated in other movements? Would he have become a starchy bishop?"

That long-ago summer of 1965, Sales, Daniels and two other civil rights workers, Joyce Bailey, 19, of Fort Deposit, Ala., and the Rev. Richard Morrisroe, 26, a newly ordained Catholic priest from Chicago, had just been released from jail in Hayneville.

They and others had been arrested six days earlier for protesting discrimination in nearby Fort Deposit, in Lowndes County, Ala., the same county where civil rights worker Viola Liuzzo had been killed by members of the Ku Klux Klan several months before.

As the group walked to a ramshackle business called "the Cash Store" to buy cold drinks, they were met at the door by Coleman, who was armed with a 12-gauge shotgun. "Get off this property or I'll blow your goddamn heads off, you sons of bitches," he snarled.

As Daniels shoved Sales aside, Coleman fired, according to historians and accounts from the time. Daniels was struck in the chest and killed instantly.

He collapsed face up just outside the store, still wearing his clerical collar and college ring.

As the others fled, Coleman fired again, cutting down Morrisroe, who was struck in the back and critically injured but survived.

After the murder trial, at which she testified, Sales eventually went back to college, then to graduate school at Princeton, and to divinity school in Massachusetts, telling no one what she had witnessed.

She tried to deal with her trauma, "tried to settle and ground myself, tried to learn to speak again without being a silent person," she said.

"I withdrew inside of myself," Sales said.

"I tried to figure out what did it mean to be young again...(while) I was still bone-weary from the war on the South."

Sales said she was raised in Columbus, Ga., where her father, a U.S. Army sergeant and combat veteran of the Korean War, was stationed at integrated Fort Benning. Her mother was a nurse.

One of five children, she had been a high school cheerleader and a student at the Tuskegee Institute, when she was inspired by teachers to join the civil rights struggle.

"I understood, intellectually, violence," she said. "But I had not come from a violent environment...I had never seen a gun in my life, to be perfectly honest. My parents didn't have weapons."

They were terrified that Sales might be hurt, or worse. Before the slaying, Sales's mother called her in distress and said she dreamed she saw Sales in a coffin with a pink dress on. "She was absolutely freaked out," Sales said.

Sales had joined the Student Non-violent Coordinating Committee and encountered Daniels during protests in Lowndes County, a place described by historian Taylor Branch as one of "feudal cruelty...(with) a filmy past of lynchings nearly unmatched."

Sales and Daniels developed a good relationship.

"He teased me because I was in the process of learning and I didn't know as much as he did about many different things," she said. "I was from the South. In many ways I was a peasant, and he came from the white elite."

"We were bridging two worlds," she said.

The day of the killing, as the group walked toward the general store, Daniels borrowed a dime from Sales, according to Branch's history of the civil rights movement.

When Coleman opened fire, Sales said, she fell down. "I thought I was also hit and dead," she said.

Bailey, meanwhile, sought cover near an abandoned car nearby, and it was not until Sales heard Bailey call her name that Sales realized she was alive.

"I crawled over on my knees and she and I ran across the street and came back over to where Father Morrisroe was lying, because he was crying for water in that hot sun," she said.

"And Tom Coleman by that time had come out of the doorway and was swinging his shotgun and telling us that if we didn't get away from Richard's body we would be also killed," she said. They fled.

She is certain that Daniels saved her life. "It was ingrained in everybody in the movement that we were each other's keepers," she said.

She praised him. "You have to understand the significance of Jonathan's witness," she said. He had graduated from the Virginia Military Institute. A doctor's son, he had studied at Harvard and at a traditionally white Episcopal divinity school.

"He walked away from the king's table," she said. "He could have had any benefit he wanted, because he was young, white, brilliant and male. "

Sales and Morrisroe are the only living survivors of the incident. Bailey died several years ago, Sales said.

Coleman died in 1997, at the age of 86. In a CBS television interview a year after the killings, Coleman said he had no regrets, according to a book about Daniels by Charles W. Eagles.

"I would shoot them both tomorrow," Coleman said.

Morrisroe, now 76, left the priesthood in 1972 and raised a family. He became a lawyer and now works as a city planner in East Chicago, Ind.

"I remember it every day," he said recently of the shooting. "I feel it in my leg every moment of every day."

He and Sales said they plan to attend Daniels's commemorations this week in Keene.

Fifty years after the slaying, Sales said, she is dismayed by the state of race relations in the country.

With all the achievements of the civil rights era, "I never imagined that there would be people working overtime to dismantle those changes," she said. "I never imagined that .?.?. once again black people would be fighting for our lives."

"I never thought that .?.?. politicians would be able to mobilize white resentment and turn that resentment against people of color," she said.

"And I never thought that at this stage of my life, as I face being close to the riverside, that now we have to walk back over territory that I thought we had fertilized forever," she said.

[Michael Ruane is a general assignment reporter who also covers Washington institutions and historical topics, at the Washington Post.]

Spread the word