Asked about his religious life by CNN's Chris Cuomo during the February 23 South Carolina town hall, Democratic presidential candidate Senator Bernie Sanders distinguished himself from his competition by declining to praise the God of Abraham. Instead, in his signature phlegmatic Brooklyn staccato, the senator discussed universal human solidarity, lifting his arms for emphasis: "We are in this togetha.

"That's not just words," he continued. "The truth is, at some level, when you hurt, when your children hurt, I hurt. I hurt. And when my kids hurt, you hurt. I believe that what human nature is about is that everybody in this room impacts everybody else in all kinds of ways that we can't even understand.

"It's beyond intellect," he concluded. "It's a spiritual, emotional thing."

Commentators who had previously criticized Sanders for downplaying his Judaism were underwhelmed by his mostly secular response. "Sanders may be focused on uniting Americans for a better future," argued the Jewish Telegraphic Agency newswire, "but some Jews would clearly like to hear him acknowledge his past."

Those Jews were eventually given voice through the unlikely agency of Anderson Cooper, who, during a March debate in Michigan, referred to Jewish leaders who were "disappointed" that Sanders keeps his Judaism "in the background." "Look, my father's family was wiped out by Hitler in the Holocaust," came Sanders's reply. "I am very proud of being Jewish, and that is an essential part of who I am as a human being." Finally, Sanders was giving commentators what they seemed to want to hear from a Jewish candidate - a reference to the Holocaust. Vox's Zack Beauchamp said the response "nearly brought me to tears."

We shouldn't be surprised by this insistence that Bernie invoke the Holocaust: Museums, school curricula, and the culture generally have so diligently cultivated the image of Jews as primarily survivors or victims of the Holocaust that we've learned to see this, and not all that solidarity talk, as properly Jewish. But Sanders carries on a Jewish tradition much longer, and more sacred, than merely paying lip service to the Holocaust. His every utterance about universal health care, economic inequality, and social justice relentlessly embraces Judaism; it's just a Judaism many people no longer recognize. Bernie Sanders is a Jew of a different era - the kind of Jew that Zionists would very much like us to forget.

The New York of Sanders's childhood was full of Yiddish socialists. Often, these were Jews of Sanders's sort, their spiritual practice less fixated on giving glory to God on high than fighting for emancipation here on earth. Although that interpretation of Judaism may seem profane, even blasphemous, at first blush, it has a firm basis in scripture.

The Torah repeatedly reminds Jews that, because we were strangers in Egypt, we are obligated in turn to welcome the stranger in the course of our lives. Scripture also tells us that our religious ceremonies are not ends unto themselves but a means through which to fortify our spirits for earthly liberation work: From Isaiah, we learn that our fasting on Yom Kippur, the day of atonement, is not for the purpose of "mak your voice to be heard on high," but rather "to loose the bonds of wickedness, to undo the heavy burdens, and to let the oppressed go free, and break every yoke."

The centuries of racial oppression and marginalization Jews have endured should reinforce these commandments, not weaken them. It is essential that we publicly enact this aspect of our Jewish identity - and choose wisely the political and social agendas we mobilize our Jewishness to advance. As Warsaw Ghetto uprising leader Marek Edelman said, "To be a Jew means always being with the oppressed and never the oppressors."

The simultaneous Jewishness and irreligiosity of Edelman's definition is itself traditional. In 1958, Isaac Deutscher, the great biographer of Trotsky and Stalin and himself a secular Jew, identified the lineage of the "non-Jewish Jew" as spiritually descended from a heretic, Elisha ben Abiyuh, nicknamed Akher ("the Stranger"). In the Midrash, an essential rabbinical exegesis on the Torah, it is written that this heretic provided theological tutelage to the revered Rabbi Meir, to whose words Jews still turn for insight: One Sabbath, Rabbi Meir and Akher were traveling and arguing, as was their custom, the heretic riding a donkey and Meir, forbidden from riding on the Sabbath, walking beside him. Meir listened to his tutor's heretical wisdom with such intensity that he didn't notice when they had reached the ritual boundary beyond which doctrine prohibited Jews from venturing on the Sabbath. Akher announced, "Look, we have reached the boundary - we must part now: You must not accompany me any farther - go back!" Meir returned to the Jewish community while the heretic, despite the respect he'd shown for his pupil's orthodoxy, rode on - "beyond the boundaries of Jewry."

This scene puzzled a young Deutscher, an Orthodox student, who wondered why Meir had listened so intently to the stranger. "My heart, it seems, was with the heretic," Deutscher writes. "He appeared to be in Jewry and yet out of it...disregarding canon and ritual, rode beyond the boundaries."

This within-and-without position is essential to Sanders's relationship not only with Judaism but with politics, too. He is a longtime Independent member of Congress who caucused with Democrats. He is running for the Democratic nomination, but with the endorsement of further-left organizations such as the Working Families Party and the Democratic Socialists of America. Throughout his career, Sanders has related to the Democratic establishment but never joined it. He is an essential fixture of Vermont politics but, as a transplant from Brooklyn, lacks even a hint of pastoral New England-ness. He titled his own political biography Outsider in the White House.

When pundits complain that Sanders is not being publicly Jewish enough, what they are really complaining about is his refusal to fall in line with the philosophy that has come to define Jewish life in America. They are disappointed that Sanders has not aligned himself with Zionism.

'Good and Bad Jews'

Last fall, news from Mediterranean Europe, dramatized by a photo of a dead toddler facedown on a Turkish beach, thrust our country into a heated debate over the ongoing refugee crisis. To counter rising right-wing xenophobia, humane people took to social media to remind us that Americans indulged a similar impulse when we rejected Jewish refugees on the eve of World War II. In both cases, though, the racist reflex contained a political component as well. Just as Islamophobia today is intimately connected to a political fear of Shariah, wartime anti-Semitism was intensified by fear of a foreign specter that would contaminate democracy: bolshevism.

Under the influence of Mein Kampf, radio priest Father Coughlin, Donald Trump's forebear in hateful demagoguery, warned of the "Judeo-Bolshevik threat": a conspiracy between Lenin, Stalin, and the rest of the Soviet leadership (all Jewish, according to Coughlin) and Jewish bankers (communist capitalists, evidently) to destroy Christianity. His counterpart across the Atlantic was no less than Sir Winston Churchill. That revered leader at least had the discernment to draw a contrast between "Good and Bad Jews," the latter of whom, he wrote, formed a "world-wide conspiracy for the overthrow of civilisation."

Opposite the "Bad Jews" of Churchill's paranoid fantasy stood Zionists, who he said would "vindicate the honour of the Jewish name." (Incidentally, Churchill couldn't help but notice, the Zionist project "would be especially in harmony with the truest interests of the British Empire.") So when the State of Israel was partitioned to life, anti-communist politicians and business interests in the West, especially the U.S., set out to destroy the left, a thriving core of Jewish life, and reorient Jewish American thought toward an increasingly reactionary Zionism.

In 1947, the Taft-Hartley Act banished communists from labor, historically a hotbed of American Jewish activism. Senator Joe McCarthy's Subcommittee on Investigations and the House Un-American Activities Committee convened witch trials that exploited the strength of the Smith and McCarran acts, which criminalized communism. McCarthy espoused the same brand of wild-eyed condemnation and suspicion that had marginalized Jews for centuries, and the implications of his prominently targeting Hollywood and labor unions, homes to both communism and Judaism, were not lost on the Christian public.

Although this crusade made Zionism look appealing by comparison, many Jews still veered left: Thousands joined the civil rights movement, appalled by the treatment of black people in the South, building on the legacy of the Jewish CIO organizers who had helped lay early groundwork for the sit-ins and freedom rides. Despite being limited in number in American society, Jews were overrepresented in activist circles: It is not a coincidence that a rabbi, Abraham Heschel, walked alongside Dr. Martin Luther King, or that two of the most prominent murder victims of the movement, Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner, were Jewish. A young Bernie Sanders was among them, too, committing civil disobedience in protest of housing discrimination in Chicago.

Many American Jews, however, took a stand on the wrong side of those struggles. In a single generation, formerly working-class Jews who'd been concentrated in the Lower East Side, Grand Concourse, and Flatbush had spread out to Great Neck, Scarsdale, and New Jersey, becoming suburban homeowners and "professionals," assimilated into that American Dream of upwardly mobile whiteness. The "there goes the neighborhood" attitude that attended white flight boiled over during the 1968 NYC teachers' strike, which pitted mainly suburban Jews against the black communities that had replaced them in what was now the "inner city." At the same time, but thousands of miles away, Israel undertook an aggressive expansion and occupation in Palestine, making manifest the country's ideological shift toward right-wing Zionism. That Zionism found voice in this country as well, becoming the most salient and powerful political philosophy for American Jews.

The magnitude of this change is difficult to overstate. The internationalism of the pre-war American Jewry was supplanted by nationalism. Our egalitarian commitment was replaced by exceptionalism. Our agitation against war was undermined by ceaseless colonialism in Palestine. Jews have been instructed that the cluster bombs and night patrols blanketing the Holy Land are necessary to preserve our heritage. We have to wonder: Has the shift to militant nationalism robbed us of a Jewish heritage worth preserving?

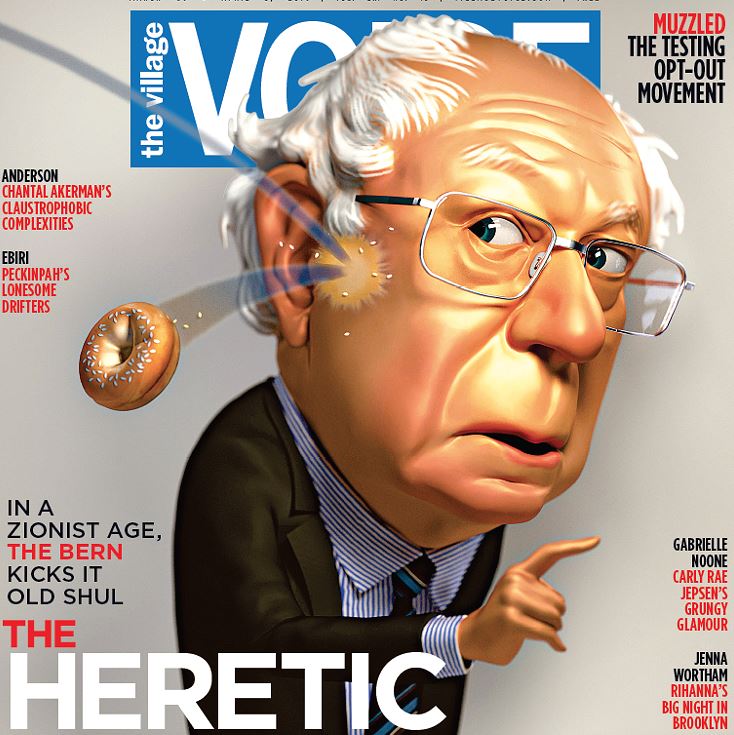

Village Voice cover (March 30 - April 5)

Drawing by Wesley Bedrosian

The Shambolic Evangelist

Zionism has given us a Judaism that bestows placards, awards, and honorary doctorates on the unrepentantly racist - lawyer and businessman Donald Sterling, for example, or the far-right political funder Sheldon Adelson. Theirs is a Judaism that, far from obligating us to oppose all atrocities everywhere, tells us that our long history of victimization actually entitles us to commit our own. The sieges and land-grabs and imprisonment sprees in the land of Canaan are undertaken to protect this Judaism, not the Judaism of Akher or the Yiddish socialists or those civil rights workers.

And yet it is the non-Zionist Sanders who is criticized for insufficient faith, even as wealthy right-wing Zionists ostentatiously parade their donations to Holocaust Museums and prestigious congregations. These gestures are supposed to fulfill the sort of public obligation Judaism imposes, but next to Bernie Sanders's dogged agitation for universal equality and justice, decade in and decade out, Zionist chest-thumping looks like a cheap substitute.

This contrast was at its starkest when Sanders declined the opportunity to join every other presidential candidate in addressing Zionism's most exalted assembly: the annual convention of the American Israel Public Affairs Committee (AIPAC). Instead, he addressed the question of Israel at a high school in Salt Lake City, Utah, in a speech that included such taboo-breaking observations as "There is too much suffering in Gaza to be ignored."

Such heresy reminds us of an earlier Judaism. When Sanders says, "We are living in a world which worships not love of brothers and sisters, not love of the poor and the sick, but worships the acquisition of money," he is not hiding his religion, but espousing it. He is evangelizing. And if his gospel is going to catch, it will most likely be among the young people who have flocked to his campaign.

My generation is already primed to abandon Zionism. For one thing, it is harder to convince people who grew up on the World Wide Web to commit to a nationalist program. For another, we have come into political consciousness seeing Israel as a violent occupying force, and responded accordingly: The number of anti-occupation, non-Zionist, and anti-Zionist Jewish youth initiatives gives a glimpse of what Jews without Israel might look like, driven not by fear of the Other but by an embrace of the Strangers of our times.

It is long overdue. Already in the 1950s Deutscher could see that Zionism was outdated. Jews "did not benefit from the advantages of the nation-state in those centuries when it was a medium of mankind's advance," he wrote. "They have taken possession of it only after it had become a factor of disunity and social disintegration." Perhaps, at long last, my generation is evincing Deutscher's hope that Jews will abandon the nation-state and return to "the moral and political heritage that the genius of the Jews who have gone beyond Jewry has left us - the message of universal human emancipation."

It will not be easy to undo the work of the past seventy years. Even now, we find fearmongering that invokes the old perils of Jewish bolshevism. But in our rejection of Zionism and our revival of socialism, young Jews are reclaiming our birthright - the right to belong to a Jewry worthy of our heritage. A heritage carried forward in the sacred heresy and grumbly evangelism of the 74-year-old Brooklyn Jew improbably running for president.

Spread the word