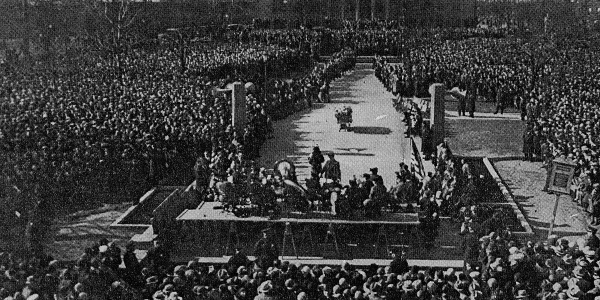

On Sunday afternoon, March 9, 1930, the city of Philadelphia witnessed what the Public Ledger called “one of the most amazing demonstrations of all trade union history,” when 22-year-old Carl Mackley was eulogized as a martyr for labor’s cause. Mackley, a knitter in the full-fashioned hosiery industry, had been gunned down three days earlier by armed strikebreakers hired by the owners of the Aberle Hosiery Mill, where a strike was in progress. The memorial for Mackley drew somewhere between 35,000 and 70,000 (depending on the source) union supporters and neighborhood residents, jamming into McPherson Square, in the heart of Philadelphia’s Kensington neighborhood, and overflowing into nearby streets. At the climax of the eulogy the assembled throng raised their right hands and took an oath to “continue the struggle against low wages, poverty and oppression,” even if it meant that they would also have to lay down their lives. This remarkable manifestation was organized by the American Federation of Full-Fashioned Hosiery Workers (AFHW), a left-wing-Socialist-led textile union that had its genesis and headquarters in the neighborhood.

Thousands gather at McPherson Square in the Kensington section of Philadelphia on March 9, 1930, for the funeral of slain striker. American Federation of Hosiery Workers Records, Wisconsin Historical Society, Madison, Wisconsin.

Later this month Philadelphia will host a spectacle of a different nature when the 2016 Democratic Convention gathers in the city. At that convention close to half the delegates, not to mention many of the protestors in the streets, will be doing something unthinkable even a few years ago: supporting a self-described socialist, Bernie Sanders, for the party’s presidential nomination. Though Sanders has now thrown his support behind the presumptive nominee, the groundswell that brought him within a few votes of the nomination remains no less remarkable. This surge in interest in “socialism” among Americans extends beyond the Sanders campaign and is evident from the many articles by pundits trying to figure out what is happening, with headlines like “‘Socialism’ the most looked-up word of 2015 on Merriam-Webster” and “Why are there suddenly millions of socialists in America?”

Of course, there aren’t “suddenly” millions of socialists in the U.S. Apparently unknown to most commentators is the rich history of the socialists, communists, anarchists, and other radicals who shaped American history in important ways. But the fact that this convention will take place in Philadelphia is particularly fitting, for there is, in fact, a long socialist history connected with the city. One little known part of that history (even to most Philadelphians), and one of the most remarkable examples of a socialist-led crusade for the rights of all working peoples, took place in the working-class community of Kensington in the 1920s and 1930s, led by the AFHW. The hosiery workers’ movement spread through the city and beyond, having a major impact on regional and national achievements of the New Deal era. They did so by building an internationalist, class-based youth movement that projected “labor” as a cause for human rights. A look at the movement they built can give some insights into what an actual socialist-led movement looked like in an American working-class community.

5,000 workers clash with police during strike at the Opal Hosiery Mills, August 2, 1935. Courtesy of Special Collections Research Center. Temple University Libraries, Philadelphia, PA.

Carl Mackley was only 22 years old when he lost his life, and many of the people who took the pledge at his memorial were equally young, for the movement the hosiery workers built was, at its core, a youth movement. In the 1920s, when many Americans were lamenting the “problem” of the younger generation, and much of the labor movement was in decline, hosiery workers forged a vision for social change aimed at achieving a better world. Many of their young workers, with the union’s young women in the forefront, internalized this vision, and they were willing to fight for it.

Silk stockings were the iconic product of the Jazz Age “flapper,” and the youth who worked in the industry not only made the product, but also participated in that culture. Although the overarching goal of union activists was to create a class-conscious movement that could bring about social change, they understood that to do so, they would need to engage the youth culture on its own terms, while honoring the historical traditions and labor culture of the organization. In the process they built a community-based movement that encompassed parties, “black bottom” dances, and sports leagues, but also a strong emphasis on grassroots, progressive, education.

Philadelphia’s Socialists of the 1920s and 1930s, in this period led by the hosiery workers, also participated in electoral campaigns. They used their campaigns to promote an egalitarian vision of rights, through a platform that called for, among other things, an end to discrimination based on race and gender, equal pay for women, universal access to birth control, universal and free healthcare and education, and pensions for elders. Although they did not win any seats in the city, in nearby Reading, home of the largest and most anti-union hosiery mill in the country, the Socialist campaign launched by hosiery workers won a landslide victory in 1927 that swept the mayor’s office, much of the town council, and even several seats on the school board.

Carl Mackley Houses showing swimming pool, with row houses and factory smokestacks in background. Courtesy of Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia Housing Projects Photographs, 1934-1940, Philadelphia Record Photograph Morgue.

But the electoral element was not the only, or even the most important part of the movement. What was of primary importance was the vision that they built–that a better world was possible through the actions of “ordinary” people. The support that Bernie Sanders has garnered among young people, in particular, is an expression of such a vision. The hosiery workers built a movement that sought to unite people across the differences of race, gender, age, and ethnicity, to build a society predicated upon justice and equal rights, political and economic, for all. One in which people took precedence over capital. They expressed this vision through addressing the rights and concerns of all members of the community for food, shelter, and a decent life; through militant strikes for fair wages and the right to representation by a union of their choice; sit-downs and lie-downs that incorporated Gandhian tactics of non-violent resistance and occupation of space; and demonstrations fighting back against the often brutal tactics of the manufacturers and labor police. Through such actions hosiery workers helped to build a broader movement, locally and nationally, that was able to push the New Deal administration of Franklin Roosevelt to address at least some of the real concerns of laboring people.

They were able to do so not by relying solely on elected officials, but by forcing change through a people’s movement and direct-action tactics. When the delegates come to Philadelphia this month they will probably not be visiting the now de-industrialized old working-class district of Kensington (except maybe the part that gentrification has claimed), but in the 1920s and 1930s that community witnessed a real example of the power that a united working class can wield. Among the accomplishments of the hosiery workers were the first workers’ housing project under the New Deal. Named after the young martyr Carl Mackley, it was built with the first loan under the Public Works Administration. Pushed by the union’s labor feminists, it opened in 1935 with a child care center for the children of working mothers, and set a precedent for later housing initiatives. Hosiery workers were instrumental in pushing through the Social Security Act and important labor legislation. Following the passage of the National Industrial Recovery Act (NIRA) in 1933, hosiery workers were the first in the nation to walk out in the ensuing strike wave, resulting in the negotiation of the Reading Formula, the primary resolution mechanism for strike settlement under the NIRA. Although inadequate, it set the stage for the later improvements of the Wagner Act. And one of their most important sit-down strikes, against the city’s Apex Hosiery Company, resulted in the 1940 Supreme Court case that removed labor from the purview of the Sherman Anti-Trust Act, thus helping to legalize labor strikes.

Crowds outside Apex Hosiery Mill tie up traffic as strikers took possession of mill, May 6, 1937. Courtesy of Special Collections Research Center. Temple University Libraries, Philadelphia, PA.

When Bernie Sanders talks about a political revolution larger than himself, it is important to understand that it must also be larger than electoral movements. Although the working class has changed from the halcyon days of yesteryear, with many jobs in service industries and precarious employment, and both manufacturing and service jobs dispersed around the world, it is still the class at the heart of the contradictions of capital, and it is time to take back its true meaning. When people come to Philadelphia this month, thinking about where the political revolution goes from here, one question that may arise is “Who will lead it?” Looking at the history of a successful, socialist-led labor movement, on the ground in an actual American city, may help give some insights into what a transformed labor movement could achieve.

____________________

Spread the word