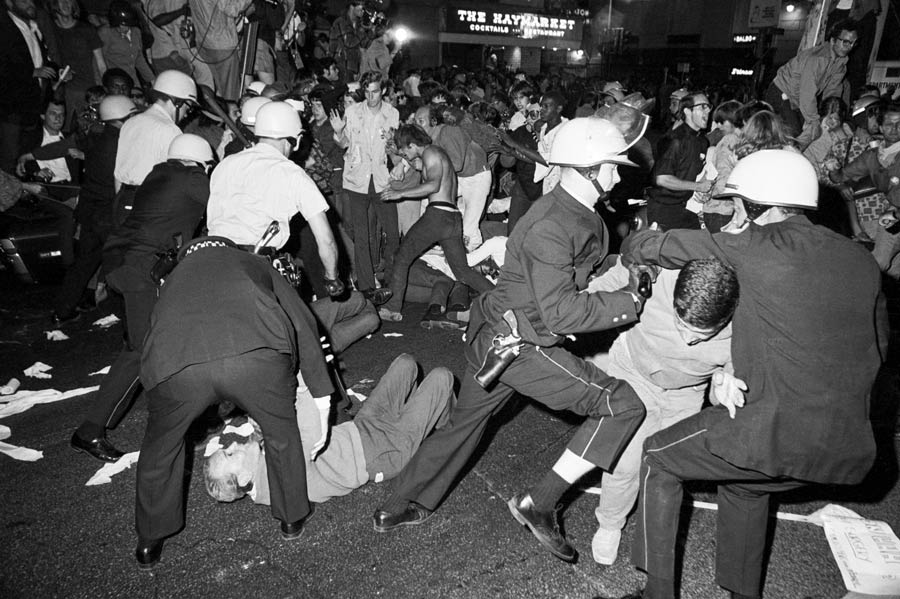

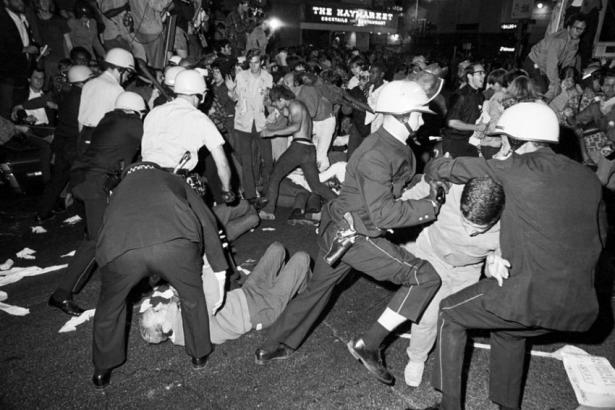

In the wake of the April 4 assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., Black communities rose up in more than 100 cities and towns. Opposition to the Vietnam War, which would ultimately claim millions of lives in Southeast Asia, grew, as did U.S. casualties. Of the more than 58,000 Americans who died from 1956 to 1975, more than 14,000 were killed in 1968. In April of that year, police savagely attacked anti-war protesters in Berkeley, Calif., and Chicago, giving the country a preview of what was to come August 26–29, when the Democratic Party held its national convention in Chicago.

The convention attracted more than 10,000 demonstrators from across the country who came to protest the Democratic establishment that had led the country into war. They were welcomed by thousands of members of the Chicago Police Department who met them with tear gas, mace and billy clubs.

Unlike the civil rights movement’s nonviolent protests, in which police attacked Black citizens engaging in civil disobedience, the optics of the Chicago demonstrations were very different.

Some of the Chicago demonstrators arrived expecting a confrontation. Todd Gitlin, writing in the San Francisco Express Times, presciently advised those coming to Chicago: “Wear some armor in your hair,” a play on the popular lyrics “If you’re going to San Francisco, be sure to wear some flowers in your hair.” Gitlin was castigated by others in the anti-war movement for depressing turnout at the Chicago demonstrations by warning that they would turn violent, but he was prophetic.

In a later interview, George McGovern put it this way:

It was a sickening thing to see. There is no question that some of the protesters got out of line. But one can’t argue that the Chicago police didn’t get out of line. They did. There was brutality. There was overkill on the part of the police, and that’s probably where we lost the 1968 . The clash between those two Americas that you could see on the street, young policemen on one hand, young protesters on the other. They were from two different worlds and that became clear to the country and that division went right through the Democratic Party.

In These Times has regularly marked the anniversary of what a government report described as a “police riot.” On the 10th anniversary, in our Aug. 30, 1978, issue, amid the malaise of the Carter presidency, David Moberg wrote:

Reporting at the time and reminiscences now, however, have been so dominated by the issue of police brutality (or demonstrator provocation) that the real point of the demonstration—opposition to the war in Vietnam—was lost to most people. … The police attack at the convention contributed to the preoccupation of many on the Left with “fighting the pigs.” pushed the New Left away from issues that could have galvanized majority backing and toward an adventurism that helped to isolate and ultimately to weaken it. … any rejected not only the Democrats, but also all electoral politics, even from the Left. Also, the overwhelming antagonism to Pig Amerika—remember the vocabulary so many of us used?—often neglected the formulation of a real alternative.

Should the convention protesters, some of whom threw stones and human excrement, have been so militant in their tactics? By appearing aggressive, did they drive “law and order” voters to Richard Nixon? By making Hubert Humphrey the enemy, did they depress Democratic turnout?

What lessons does the battle of Chicago have for us today, when there’s anger at the Democratic establishment but also the purported danger of driving voters into the arms of Republicans, the forces of Donald Trump? On June 19, as rage mounted over immigration authorities tearing children away from their parents, Homeland Security Secretary Kirstjen M. Nielsen was hounded out of a restaurant by Democratic Socialists of America activists, one of whom yelled, “In a Mexican restaurant of all places? The fucking gall. Shame on you, fascist pig.” Critics of the action warned that this and similar breeches of much-invoked “civility” would all play into Trump’s hands.

Who reaps the most benefit from such protests? We asked three veterans of 1968 and one historian of the period to revisit this 50-year-old debate.

Joel Bleifuss is editor and publisher of In These Times.

Blame the Democrats, Not the Protesters

By Marilyn Katz

Conventional wisdom and a variety of academics, such as David Farber, author of Chicago ’68, hold that the lawlessness of the youth in Chicago’s streets drove voters to Richard Nixon, “the law and order candidate,” and helped usher in decades of Republican rule. They blame the uncouth demonstrators for the demise of the Democratic Party and the Left.

It is time to challenge those historical assumptions, not simply to set the record straight, but because our understanding of the past influences our strategies for a progressive future.

The reality is that it was racism—not cultural politics or demonstrations in the street—that caused a majority of white voters to abandon the Democratic Party. And it was the Democratic establishment’s inability to embrace new political realities that resulted in the squandering of the progressive vote that might have spelled victory and a different history.

We think of 1968 as the watershed year when Richard Nixon’s “Southern strategy” made the South a permanent fixture in the Republican Party camp, but the shift began earlier. In 1960, Democratic presidential candidate John F. Kennedy praised the lunch-counter sit-ins challenging segregation. “The American spirit is coming alive again,” he said. The Democrat-lauded March on Washington was in August 1963, one year before the Civil Rights Act made employment, residential and other discrimination a crime.

In 1964, Lyndon Johnson won the presidency with a larger margin of victory than John Kennedy, but he lost the Deep South, turning Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia and South Carolina into Republican strongholds, a position they maintain today. Then came the Voting Rights Act of 1965 and the ensuing white backlash, and the 1967 Loving Supreme Court case, which legalized mixed-race marriages.

In 1968, Hubert Humphrey lost to Nixon, 42.7 percent to 43.4 percent, with 13.5 percent of voters choosing segregationist George Wallace.

It is ironic—and explains much about the advent of President Donald Trump—that while the media and Democratic strategists were blaming the lawlessness of the demonstrators for Nixon’s victory and counseling that we should all be “better behaved” if we wish to win in the future, only Republican political strategist Kevin Phillips recognized the more important underlying dynamic. He wrote:

From now on, the Republicans are never going to get more than 10 to 20 percent of the Negro vote and they don’t need any more than that. … The more Negroes who register as Democrats in the South, the sooner the Negrophobe whites will quit the Democrats and become Republicans. That’s where the votes are.

The lack of understanding of racial politics is compounded by a tendency to blame Humphrey’s loss on those who weren’t willing to compromise. Pundits like my friend Todd Gitlin too often castigate the young, the anti-war forces, women and blacks for not holding their noses and voting for Humphrey.

I disagree. The mistake was not ours, but that of Chicago Mayor Richard Daley, the Democratic National Committee (DNC) and Democratic elected officials. With his brutal, senseless suppression of demonstrations, Daley managed to make the Democratic Party and the Chicago police the focal point of ire, rather than the war that people had come to protest. As for the DNC, had it chosen to embrace an anti-war, pro-choice, anti-poverty agenda— the agenda being fought for in the streets—we would have voted and Humphrey might have won. Our protests were not a diversion from the politics of the moment: We were the politics of the moment.

Why bring up this 50-year-old history now? Because the racism that underlies Trump’s rhetoric, actions and base is starkly similar to the racial politics that Phillips described nearly 50 years ago. So, too, is the challenge that the Democratic Party faces today, as evidenced in the 2016 election and the subsequent DNC leadership fight: Whether the party should to continue to search for and win that elusive white male moderate voter (a la Hillary’s campaign) or fully embrace the progressive and racially diverse politics of the newly energized constituencies of women, radical labor, LGBTQ activists, Latinos, African Americans, youth and socialists (in all their intersections).

If the Democratic Party hopes to win, it must represent us—all of us—and boldly.

Marilyn Katz is a public policy communications strategist, writer and political activist. She was called to action by the civil rights movement and the war in Vietnam while a student at Northwestern. In 1968, as an organizer with JOIN Community Union, she organized Chicago high school students—an activity that led her to be head of the “marshalls” in the April and August demonstrations.

Bettman/Getty Images // In These Times

Our Hands Aren't Clean

By Todd Gitlin

What galvanized the decades-long Republican swerve into the arms of white supremacists and the vilest of America Firsters? Marilyn Katz is right that too much can be made of the inflammatory impact of the 1968 demonstrations themselves, for, as she writes, racist hatred of civil rights was the prime culprit, along with Lyndon Johnson’s commitment to the monstrous and stupid Vietnam War. Still, I can’t agree that the mistake that caused Hubert Humphrey’s loss in 1968 “was not ours, but that of Chicago Mayor Richard Daley, the Democratic National Committee (DNC) and Democratic elected officials.” Of course, Daley’s police wielded the violence, but the movement made it too easy for them. The street-fighting approach to politics had been mounting throughout 1967 and ’68. Police aggression in the Bay Area, Chicago and New York left little space for nonviolence. Streetfighting, however, regardless of who was primarily responsible, worked to the Republicans’ advantage.

Richard Nixon was poised to make the Chicago violence work for him with a “law and order” appeal, piggybacking on Daley’s view—endorsed by most Americans—that the demonstrators were to blame. Some of the organizers—provocative, desperate and indifferent to the costs of boiling polarization—played into their hands. When Daley denied overnight permits in Chicago parks, the demonstrators’ move into the streets made them look like aggressors in the eyes of many. Tom Hayden, a key organizer, urged demonstrators to “turn this overheated military machine against itself” and “make sure that if our blood flows, it flows all over the city.”

Government provocateurs played their parts in heating up confrontations that played better for police, once televised, than for the demonstrators. (For details on some known provocations, see John Schultz’s masterful No One Was Killed.)

All the major players made crushing mistakes, and no one’s hands were clean. Sen. Gene McCarthy (D-Minn.) partly walked away from his own campaign after Robert Kennedy’s murder. McCarthy, had he been willing to play political hardball, might have tried to broker a deal with Humphrey, offering to campaign for him in exchange for backing away from the war. In late October, Johnson and Humphrey declined to go public with their knowledge that Nixon was committing treason by interfering in the Paris peace talks to sabotage a deal that would have worked to Humphrey’s benefit.

Had a few hundred thousand anti-war Democrats held their noses and voted for Humphrey, he could have corralled enough votes to throw the presidential race into the House of Representatives, where the Democratic majority would have put him over the top.

Defeat has many masters, and history is paved with unknowables, both known and unknown. There’s a special chamber in purgatory, maybe an airlock, reserved for those who can never stomach a vote for the lesser evil. I’ll join my friend Marilyn there, not having voted in 1968. After Bobby Kennedy’s assassination, in fact, I advocated a write-in vote for Kennedy and Martin Luther King Jr.—a naive notion that would have been nothing more than an empty gesture. In the wretchedness of history, purgatory is an even vaster territory than the hotter place, where Ralph Nader and Jill Stein later carved out their sanctums.

The lesson I had barely begun to learn in 1968 is this: When the leading institutions and the top players act monstrously, the opposition is not morally free to stop thinking. It has to judge the consequences of its actions. The powers that be are not omnipotent. The powerless, as former Czech President Vaclav Havel wrote, have some powers. “My hands are clean,” “the enemy is loathsome”—such defenses are abdications of moral choice. When al-Qaeda and ISIS massacre civilians, when the Khmer Rouge commits genocide in the name of anti-imperialism, when the Weather Underground plans to bomb a dance at Fort Dix, purity of principle is no alibi. Virtuous ends do not justify counterproductive means—period.

Todd Gitlin was the third president of Students for a Democratic Society. In 1968, he wrote for underground papers, including a daily published by Ramparts magazine in Chicago. He teaches journalism, sociology and American studies at Columbia University, and wrote about the Democratic convention in The Sixties: Years of Hope, Days of Rage.

Bettman/Getty Images // In These Times

It's Complicated

By Don Rose

F. Scott Fitzgerald once wrote, “The test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposed ideas in the mind at the same time and still retain the ability to function.” Which is another way of saying that the legacy of the 1968 convention demonstrations—which I helped organize from the gitgo—is mixed. Opposing analyses of that legacy each have value: It’s not “either-or” but “both-and.”

I don’t see how anyone can deny that the reaction to the police riots was a major contributing force to Richard Nixon’s 301–191 electoral vote margin of victory. All national polling following the event showed substantial majorities of the public favoring Chicago Mayor Richard Daley’s bludgeoning cops and opposing those shit-throwing radicals. Yes, Daley won the propaganda war and it certainly had an electoral effect 69 days later.

But remember, similar majorities opposed sit-ins, freedom rides and even Martin Luther King Jr. and nonviolent civil rights demonstrations. Racism was clearly a driving force in the 1968 election—witness the substantial vote George Wallace got even outside of deep Dixie (though Hubert Humphrey carried Texas and West Virginia). On the other hand, racism indirectly helped Humphrey: The Wallace vote drained enough from Nixon in states like Connecticut and Pennsylvania to enable Humphrey to carry them, much as the Ralph Nader vote defeated Al Gore in New Hampshire and Florida. One can argue that, while racism was the dominant force, reaction against our side probably tipped it to Nixon, who of course exploited racism himself.

But no traditional electoral analysis supports the idea that Humphrey lost because of write-ins and left-party votes.

To be sure, there is no way of counting those who simply did not vote out of left-wing protest. One might argue that, had Humphrey broken with Johnson on the war a month earlier, the positive reaction might have gathered enough momentum to win. Might.

Elections are complex. Rarely can a single matter prove the decisive factor. Did Hillary Clinton lose because of James Comey? Sexism? Emails? Stupid statements and a lousy campaign? Russian interference? Take your pick.

On the other hand, there is a positive legacy to ’68. Nationally, the Democrats gave us the McGovern-Fraser reforms, developed by a committee headed by the then-senator and 1972 presidential candidate. These largely took candidate selection away from the party bosses by requiring primaries or caucuses in every state, and instituted racially- and gender-balanced delegations to the convention. Although they made up a minority of voters, many onlookers were sympathetic to our side of the Chicago clashes and joined the peace movement. It was a link on a chain leading, however tardily, to Congress voting to cripple the war by blocking funding in 1974.

Here in Chicago, disgust with Daley and his police actions helped build an independent Democratic political movement, largely centered on the north lakefront (hence the archaic legend of the “lakefront liberal”). In 1969, the white North Side elected an independent alderman and later a swarm of independent delegates to the Illinois Constitutional Convention of 1970, which became one of the strongest of any state on civil liberties—even if it doesn’t permit a graduated state income tax.

Hold those opposing thoughts in your head as we journey forward.

Don Rose is a Chicago political consultant and writer and has been active in social movements for more than 60 years. He was Martin Luther King Jr.’s local press secretary during his Chicago campaign (1965-67) and was an organizer and press spokesman for the National Mobilization Committee to End the War in Vietnam in 1968, and later a cofounder of Chicagoans Against the War in Iraq.

If Nixon had Lost

By Rick Perlstein

The most important thing about the 1968 DNC demonstrations was that a majority of the Americans who watched them on television sided with the cops. Their tribunes, Richard Nixon and George Wallace, got 57 percent of the presidential vote that November, in part by tapping into the grievances revealed by angry reactions to the protests.

Then, history played a cunning trick. The reactionaries just got angrier, and angrier, and angrier—even as what they said they were reacting against grew milder with each passing year. The object of their wrath was not a movement bent on fucking in the streets (the mock-demand of the Yippie-aligned White Panther Party), or assaulting the citadel of the Democratic Party, or crippling the American war machine, but—well, read Hillary Clinton’s 2016 platform. It wasn’t bad, but it certainly wasn’t revolutionary. Only, that is, if you don’t watch Fox News, where milquetoast Democrats come off worse than Pol Pot.

None of this history is reasonable. None of it makes for neat, 50-years-on “lessons.” Less still should it provide an occasion for 50-year-old score-settling about who should have done what and when.

Was the Republican reaction driven by racism? Of course it was. But that doesn’t erase what happened in Chicago from the historical ledger. For, as the historian Frank Kusch explains in the most revelatory and finely observed book on the Chicago convention, Battleground Chicago: The Police and the 1968 Democratic National Convention, a lot of what the cops were up to that week in Chicago was a sort of wildcat strike against their employers, who did not let them knock in enough heads in the April 1968 West Side riots after Martin Luther King’s assassination. If the broader public, after its fashion, liked what they saw, this was because of an easy conflation: It was just as satisfying to bash the head of a hippie as it was an uppity black; any offender against the cult of the bourgeois enclave would do. This conflation was not incidental to right-wing reaction in the 1960s and the years since, but, rather, defined it. “Law and order,” as the Republicans used to say. (And, oh, wait: They still do.)

Should the protesters have been demonstrating? Well, not many did. Only 10,000 showed up in Chicago, when organizers dreamed of hundreds of thousands. Should Hubert Humphrey have, early and aggressively, come out for ending the war? Of course. For one thing, if he had, he probably would have won. But maybe not. For it was not only history that was cunning. Richard Nixon was, too. Many of the people who voted for Nixon did so not only because they thought he’d give it to the hippies but because they thought they had heard him promise to end the Vietnam War. Never forget: One reason reactionaries often prevail over liberals—and lefties—is that they are so much more willing to lie.

There was another reason Nixon won: He promised, in every speech, to make America quiet again. Because, in 1968, everywhere Democrats went, anarchy seemed to follow. During one speech for Humphrey during the convention, a woman marched toward the speaker, naked, with the head of a pig on a platter. Then, during the general election, Humphrey was heckled by anti-war protesters at nearly every speech—that is, when they were not throwing things at him or (in one instance) pouring blood into a fountain next to which he was speaking.

Todd Gitlin is right: They should have been holding their noses and voting for him. Had Humphrey won, maybe he would have done what he later did, as a senator, which was to team with Rep. Augustus Hawkins (D-Calif.) of Watts to propose a full-employment bill that would have required the government to provide a job, at prevailing wages, for every American who wanted one if the unemployment rate rose above 3 percent. Or the bill he wrote with Sen. Jacob Javits of New York—a Republican!—to set up a national system of industrial planning. In other words, had Humphrey won, he might have worked to turn the United States into a democratic socialist society. And yet, this is the man who the New Left decided was merely a monstrous reactionary. Had he won, the Democrats might not have become Bill and Hillary Clinton’s party.

Rick Perlstein, an In These Times contributing editor, is the author of Nixonland: The Rise of a President and the Fracturing of America.

Reprinted with permission from In These Times. All rights reserved. Portside is proud to feature content from In These Times, a publication dedicated to covering progressive politics, labor and activism. To get more news and provocative analysis from In These Times, sign up for a free weekly e-newsletter or subscribe to the magazine at a special low rate.

Never has independent journalism mattered more. Help hold power to account: Subscribe to In These Times magazine, or make a tax-deductible donation to fund this reporting.

Spread the word