An interview with Jody A. Forrester, author of Guns Under the Bed: Memories of a Young Revolutionary, published on September 1, 2020, by Odyssey Books (AU)

In the late 1960’s, Jody Forrester transitioned from love child to peaceful Vietnam War protester to membership in one of that era's new revolutionary organizations. The Revolutionary Union (RU) - forerunner of today's Revolutionary Communist Party - based itself on Marxism-Leninism-Mao-Zedong Thought, believing that violence would be necessary to rid the U.S. of its capitalist ruling class. In keeping with that perspective, Jody slept with guns under her bed to stay ready for confrontations with the police and right wingers, and eventually the anticipated uprising.

Silent about her three-years in the RU for many decades, Jody decided only recently to share her experience with family, friends and the general public. The result is her memoir, Guns Under the Bed: Memories of a Young Revolutionary, The question that she seeks to answer in the volume is based on the activities of a single night when she and her comrades armed themselves in her living room, guns pointed at the front door, expecting a police raid. That didn’t happen but it made her question: Would she have pulled the trigger? I spoke with Jody about those times, about what led her to such a singular path, and where she went from there.

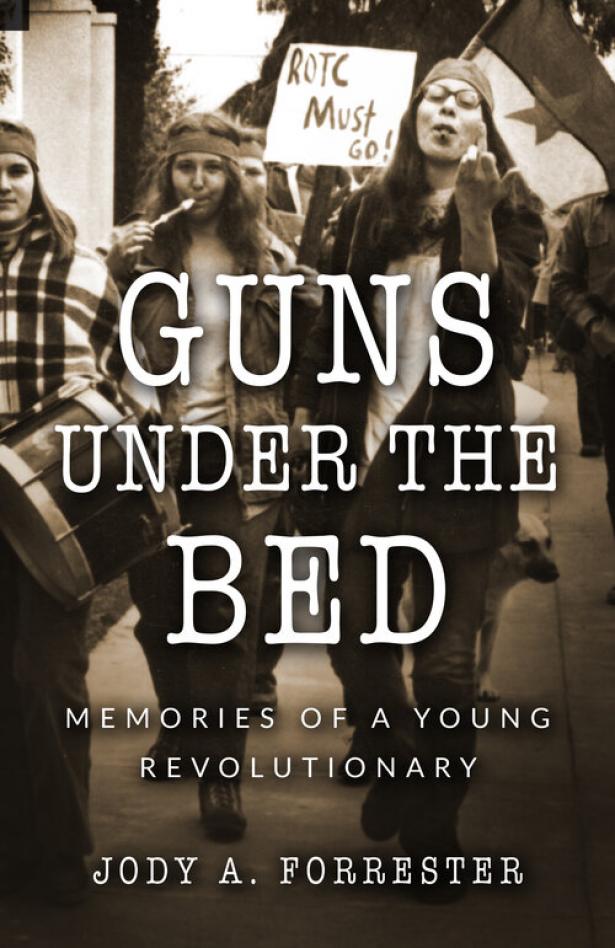

ME: People shopping for books will often pick up or reject a book based on its cover. Guns Under the Bed features a sepia-toned photograph of you leading a march, holding a sign that declares “ROTC OFF CAMPUS,” a kazoo in your mouth, and the middle finger of your left finger pointing up. It intrigues. Do you remember that day?

JF: In truth, I don’t really recall that particular day because there were so many protests that I participated in against the ROTC. They came often to San Jose State University to recruit students into their ranks. To us they represented the military imperialists who were vanquishing Vietnam. We felt they had no right on campus.

ME: Then there’s the title: Guns Under the Bed: Memories of a Young Revolutionary. Were there really guns under your bed? How did you feel about that?

JF: When my boyfriend at the time moved in with me, he stashed two rifles under our bed – a 30-00-6 and a M1. They were there in readiness for the anticipated uprising against the ruling class. I wasn’t at all comfortable with them in our bedroom. I tried to talk him into moving them but he insisted they remain. I really didn’t have it in me at the time to overrule his desires. Hierarchically he was above me in the RU so I had no clout. But I never forgot they were there.

ME You were an active Vietnam War protester while still in High School in Los Angeles. Once a freshman at San Jose State University, you were drawn to the Revolutionary Union. What attracted you? What were your expectations?

JF: Early in the first semester I went to an anti-war rally on campus, hoping to find like-minded people who I hoped to make friends with. A series of speakers ranted against the war but had nothing to say about what could be done. Then Joe, a member of the Revolutionary Union, came up on the stage. His speech was controlled and eloquent, saying “Our (Revolutionary Union) organization has tactics and strategies toward the day when all that is wrong will be set right.” If not said exactly, that’s what I heard. Wrongs will be set right.

Listening to Joe, I comprehended that rather than amorphous and multiple enemies too many to take on, there were only the twinned swords of capitalism and imperialism. By then, I was beginning to understand that love might not be enough of an answer to the many disparities in the world, not when we were dealing with a government that cared only for protecting the rich and entitled. As I learned more about the Revolutionary Union, and its possibilities for the future, the more attractive it was.

I was inspired, confident that the devil that could be named could be defeated. If Joe was right, if those swords were crushed, then one day we would live in peace, one day nobody would be hungry, wealth would be shared, and all would live a better life. Fueled by his enthusiasm, his words gave me hope when I truly needed it.

ME: What led you to leave the RU? What was life like immediately afterwards?

JF: I was a member for three and a half years. During that time, nothing was more important to me than achieving our goals of a working class led revolution, but in many ways I just couldn’t commit fully. My basic nature is to be inclusive, to listen, and to validate people’s feelings, which doesn’t fit the recommended personality of a good communist. The goal of any Maoist is to recruit new members to the cause. Personal connections are discouraged. The only conversation one should have is about the theories and practices of Mao Tse-Tung but I just wasn’t good at it. Looking back, I understand that I didn’t have the confidence of my convictions. That isn’t actually why I quit but after three years I was beginning to question whether the path I was on was the right one for me personally.

At the end, I was jumped and beat-up by three young Chicanos who thought I was a gay male. To my shock, the organization’s response was that as lumpenproletariat’s (the unorganized and apolitical lower orders of society who are not interested in revolutionary advancement), I shouldn’t expect them to be tolerant. Outraged by his betrayal, I quit in a temper of rage.

But leaving the security and protection of the RU was one of the hardest times of my life. For more than a year, I floundered, neither here nor there. Having lost the vocabulary to form personal relationships, it took a long time to let people get close to me again. Almost 21, I had missed the rites of passage of that age, so had to catch up and reinvent myself at a time of great vulnerability. It was tough.

ME: Your memoir must to have been challenging to write. What motivated you to explore that time of your life?

JF: A year after leaving the RU, a congressional committee published a government document called Radicals and Revolutionary of the California Bay Area. My name and picture was listed along with my many comrades. They confronted my parents, they confronted my supervisor at the semiconductor plant that I worked at, and followed me to the places that I interviewed with and sabotaged those possible jobs. Unable to find work, I left San Jose and moved to Vancouver. The first people that I met there were completely apolitical, and in what conversation could I share that I had once been a communist? Without conscious thought, I sequestered that time in my life, speaking of it to nobody. There were two reasons for that: shame that I had gone so far out there and guilt for not being able to stick it out. The silence became habitual and moving on from there I never spoke of it until I met my husband in 1980.

Still, the secret festered until a conversation with a writing instructor ferreted it out, telling me that that was the story that I needed to tell. By then I was a short fiction writer, and at first attempted to write it as such, but found it impossible to maintain a fictive point of view about events that had really happened. Thus, a memoir about the ignored and unexplored time in an otherwise well-explored life.

Like anyone writing about their life, there were many roadblocks of memory and I had to dig deep but I trudged through, each draft deeper and more honest than the last. Yes, it was challenging.

ME: Now long past that time, looking back, what was right, what was wrong?

JF: I have long forgiven myself for throwing myself so full-heartedly into an organization that promoted violence. I was young, angry, and an idealist, searching for a way to make the world a better place. While no longer believing in the ideology, I still have the same ideals. I still believe that imperialism and capitalism are the scourges of democracy.

ME: There's a whole new wave of protest and radicalization like the late 1960s underway now. Any thoughts on what your experience means in this new context?

JF: I believe that my experience, especially as a female, is both timely and relevant as an account of the struggles against the ruling class. From the sidelines, I have been cheering those on the streets for Black Lives Matter and against police brutality. We laid the groundwork; it’s important for protesters today to know the narrative of the activist movement in the sixties and seventies—after all, it is their history. Our demonstrations effectively put an end the Vietnam War but how did we accomplish that? By forming coalitions, marches, boycotts, et al. Witnessing the Millennial’s on the streets, (which to my pride include my younger daughter and her friends), their response sans the leadership of a paternalistic and hierarchical organization may well be our salvation.

Max Elbaum is the author of Revolution in the Air: Sixties Radicals Turn to Lenin, Mao and Che, a history of the late 1960s-1980s "New Communist Movement" in which the Revolutionary Union that Jody Forrester joined played a pioneering role.

Spread the word