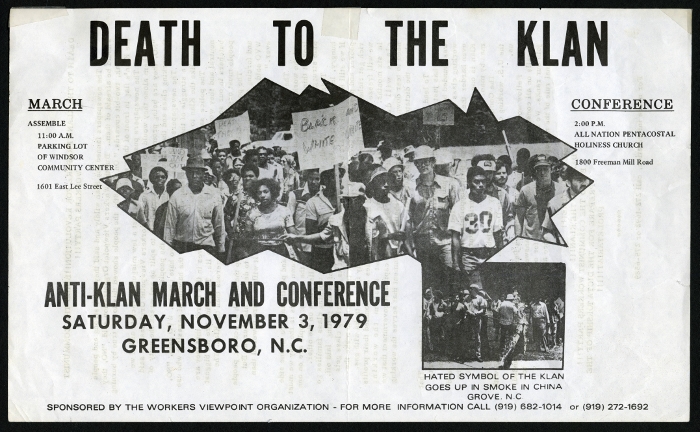

"Death to the Klan!” On Saturday, November 3, 1979, that chant swept over Morningside Homes, a mostly black housing project in Greensboro, North Carolina, as dozens of protesters—some donning blue hard hats for protection—hammered placards onto signposts and danced in the morning sun.

The American left had largely given up on communism by then, but these demonstrators were full-on Maoists. Their ranks included professionals with degrees from places like Harvard and Duke. And they were descending on Greensboro, a city where sit-ins helped launch the civil rights movement in 1960, to ignite another revolution. They danced to a guitar player singing, “Woke up this morning with my mind set to build the Party.” Their children dressed in tan military shirts and red berets. They even brought an effigy of a Klansman, dressed in a white sheet and hood, which kids from the neighborhood joined in punching.

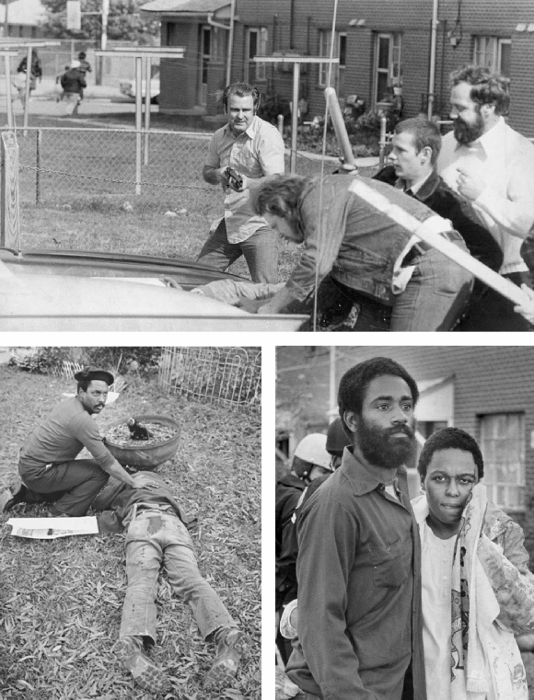

The communists planned to begin their march at noon, moving from the housing project to a local shopping center. But just after 11:20, a caravan filled with real Klansmen and Nazis surprised them, snaking through the neighborhood’s narrow byways. As the protesters stood their ground, a man in a white T-shirt leaned out the passenger window of a canary-yellow pickup truck, and yelled, “You asked for the Klan. Now you got ‘em!” The station wagon behind him carried four Nazis. Seven more vehicles followed, carrying nearly 30 more men, including an Imperial Wizard of the Klan.

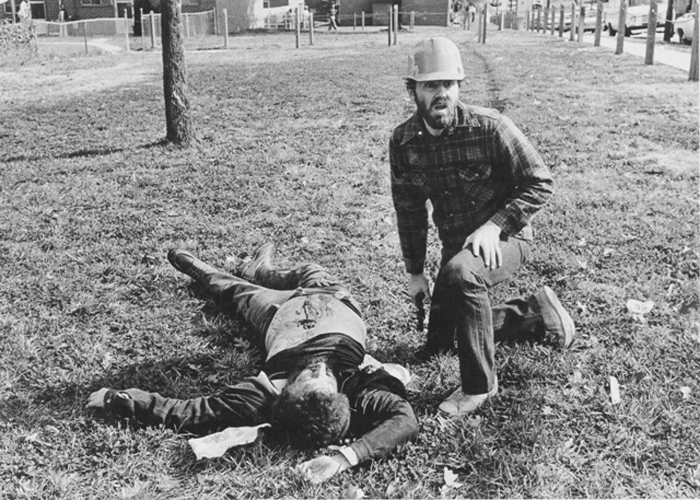

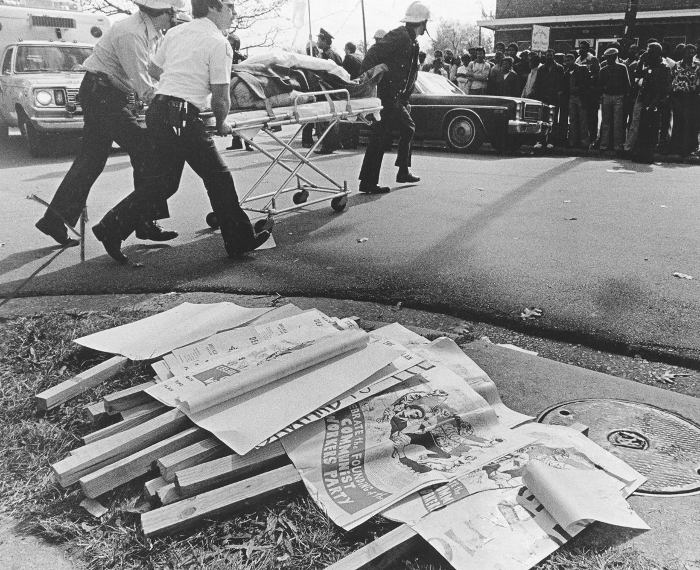

What happened next took just 88 seconds, but still reverberates 40 years later. In a confrontation where white supremacists began firing pistols, rifles and shotguns, and with television cameras rolling but police nowhere to be found, five communists were shot dead in broad daylight. Ten others were injured, some left to lie bleeding in the streets.

Greensboro News & Record // Politico

But that November morning became momentous for more than the grotesque video footage that still lives on the Internet: The Greensboro Massacre, as it became known, was the coming-out bloodbath for the white nationalist movement that is upending our politics today.

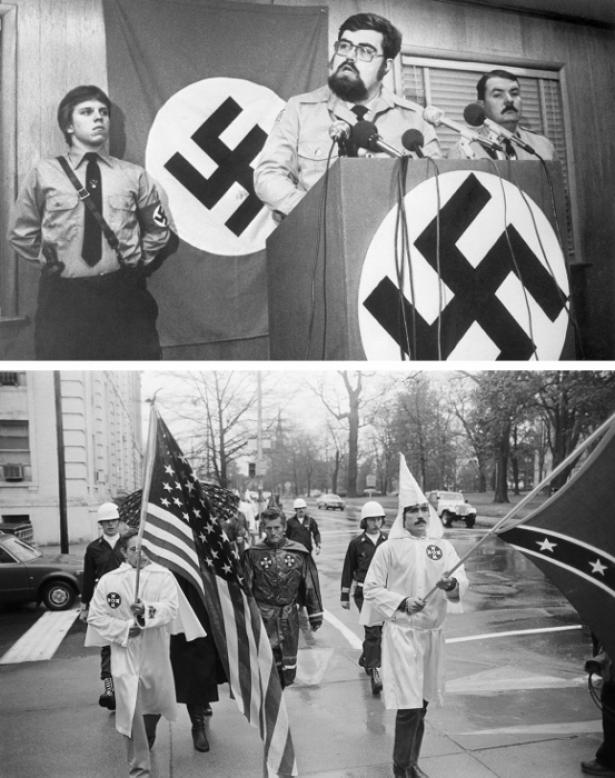

Before Greensboro, America’s most lurid extremists largely operated in separate, mutually distrustful spheres. Greensboro was the place where the farthest-right groups of white supremacy learned to kill together. After November 3, 1979, it was suddenly possible to imagine Confederate flags flying alongside swastikas in Charlottesville. Or a teenager like Dylann Roof hoarding Nazi drawings as well as a Klan hood in his bedroom while he plotted mass murder.

Today, white nationalism is closer to the mainstream of American politics than ever before. The far right’s fears about “replacement” of the white race and outsider “invasions” have become standard tropes at conservative media outlets, and its anger is routinely stoked by the president of the United States. At the same time, right-wing violence is on the rise: Far-right terrorists accounted for the overwhelming majority of extremist murders in the U.S. last year, according to a January report by the Anti-Defamation League.

The seeds for this iteration of white supremacy were planted 40 years ago in Greensboro, when the white wedding of Klansmen and Nazis launched a new, pan-right extremism—a toxic brew of virulent racism, anti-government rhetoric, apocalyptic fearmongering and paramilitary tactics. And this extremism has proven more durable than anyone then could imagine.

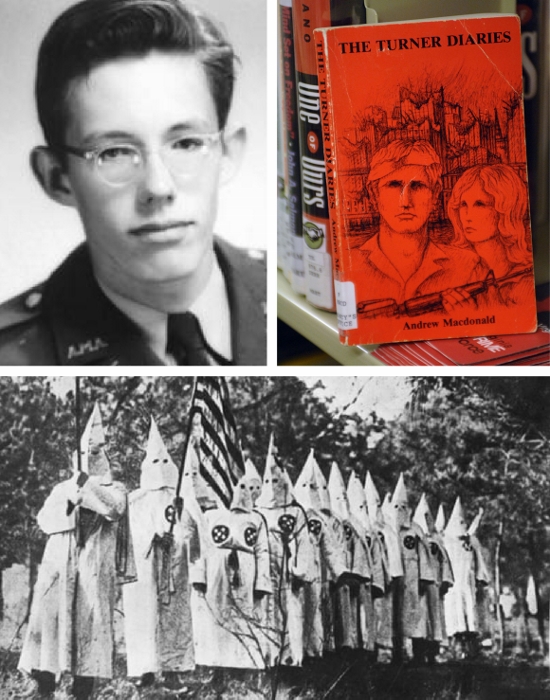

Segregationists of the Greatest Generation, who fought German soldiers on the battlefields of World War II, would have thought it beyond preposterous for the Klan and Nazis to make common cause. Adolf Hitler drew inspiration from Jim Crow, but American southerners strongly supported going to war against Nazi Germany. In 1946, a list of American Nazi Party members, obtained by the U.S. Army, showed that just two percent lived in the South. Nazis were dedicated to the violent overthrow of the government, as part of their program of genocidal fascism. Through the 1950s, most neo-Confederates considered themselves patriotic Americans and had faith in the U.S. political system, even as they believed in and practiced white supremacy.

But many southern traditionalists experienced the upheavals of the next two decades as a series of betrayals. By the mid-1970s, federal courts had embraced civil rights, and civic and business leaders were dismantling legal segregation. Manufacturing, textile and tobacco jobs were vanishing. Politicians on the cosmopolitan left and corporate right were abandoning blue-collar voters. Vietnam veterans were coming home unappreciated and embittered. In addition, the FBI, after years of pursuing black nationalists, began infiltrating and undermining local Ku Klux Klans through a program, largely forgotten today, called COINTELPRO-White Hate. To be sure, only a small fraction of angry southerners turned to terror groups. But the Klan’s membership grew in the ’70s, and so did its public support. Gallup reported in 1979 that 11 percent of white Americans viewed the KKK favorably, up from just six percent in 1965. And with that rebound came something more: Those who were susceptible to recruitment were far more likely than their parents or grandparents to see the U.S. government itself as an alien force bent on destroying the white way of life.

Wikimedia Commons; AP Photo; Getty Images // Politico

Meanwhile, American Nazis were expanding their public presence. Some younger would-be fuhrers began trading armbands for sport coats and toning down their rhetoric in media appearances in order to seem more palatable. Other Nazi leaders, like William Pierce, head of the white separatist National Alliance, started looking for partners and muscle, hoping to turn far-right fanatics from vigilantes to insurrectionists. In 1978, Pierce published The Turner Diaries, a futurist fantasy-cum-blueprint for all-out race war. In Pierce’s novel, oppressed whites join forces to create an underground organization that bombs New York and murders thousands of black and Jewish people, among many other horrific acts; the book’s protagonist ultimately flies a nuclear warhead into the Pentagon. The Turner Diaries was a huge hit with the far right, and has influenced a wide spectrum of racists—and inspired notorious hate crimes—ever since.

It wasn’t just avowed racists who gravitated to new extremes. In the weird, unusually rootless time between Watergate and the election of Ronald Reagan in 1980, America’s faith in public institutions collapsed, cynicism soared and belief in a wide range of conspiracy theories and cults, from UFOs to the Unification Church, sprouted in popularity. But those rooted in racial resentment took hold in especially bitter soil. White supremacists of all stripes came to believe they faced annihilation, and they prepared to fight it on the home front. The country, in other words, was primed for a fusion of the ultra-right.

***

The story of the Greensboro Massacre really begins with an episode that occurred in the summer of 1979, in a tiny, working-class city 60 miles to the southwest, called China Grove.

Klan leaders in North Carolina had spent the first half of the year stepping up their recruitment efforts by appealing to the heritage of white supremacy. The Federated Knights of the Ku Klux Klan, for example, staged a historical exhibit at the Forsyth County Library—and in an early sign of what was to come, a group of Nazis showed up to ogle the items on view, surprising the media.

On July 8, the same North Carolina Klan faction tried to screen The Birth of a Nation, the 1915 racist epic that depicts heroic figures in white hoods trying to beat back the scourge of Reconstruction at the turn of the century, at the China Grove Community Center. But before they could show the movie, more than a hundred protesters, led by communists from Durham and Greensboro, marched on the building, chanting “Death to the Klan!” and “Decease the rotten beast.” Many carried pipes and chains.

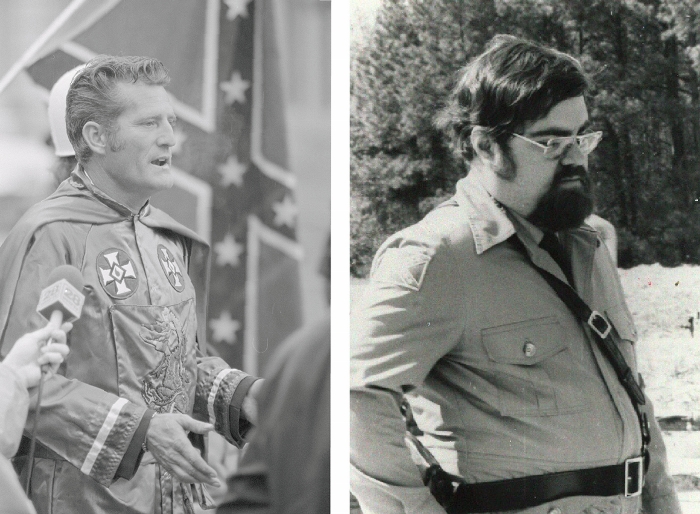

The Grand Dragon of the Federated Knights, a pot-bellied mason named Joe Grady, stood on the porch outside the building with some 20 men in robes and white-power t-shirts, rifles drawn, while members of the China Grove police force struggled to create a human buffer. Grady’s men were eager to fire on the crowd, but a policeman who walked up to him whispered that if they did, the officers trying to keep the peace were the ones who would get hurt. Grady reluctantly agreed to move into the musty bingo hall, where women and children who had been watching the approaching crowd were hiding. Once the Klansmen retreated, a cheer rose up from the protesters, who burned a pair of Confederate flags.

Afterwards, once the crowd was gone and the screening cancelled, Grady re-emerged to face the news cameras. Grabbing a shred of burned flag, he vowed, “There will be revenge for this.” But while Grady put on a brave face for the remaining television cameras, in the eyes of his hooded peers, he had committed a cardinal sin. He had allowed himself to look weak.

By that point, the Klan’s resurgence was already triggering confrontations around the country. In Decatur, Alabama, in May 1979, more than a hundred armed Klansmen blocked a civil rights march. Later, that August, rock-throwing protesters pelted Klansmen at an anti-immigration meeting in Castro Valley, California. None of those episodes led to lethal retaliatory violence, however. China Grove was different because it got the attention of a young Nazi named Harold Covington.Born about 20 miles east of Greensboro, Covington had attended an integrated high school in Chapel Hill, where he proudly called himself the “school fascist.” Jowly and glib, Covington traveled to South Africa where he built a minor reputation as a soldier-for-hire who’d taken up arms to defend apartheid. By the time he resettled in North Carolina and launched a losing but surprisingly well-run campaign for Raleigh city council, Covington had become an articulate, publicity-seeking ideologue, with a sideline writing campy novels—a kind of L. Ron Hubbard of the racist resistance.

Getty; Courtesy of SPLC // Politico

With a sense of himself as a global figure, Covington regarded most Klansmen he met as boorish. The backlash to China Grove convinced him they were also in disarray. And Covington saw no one in the back-country klaverns of North Carolina capable of stepping into the void. Long before he would become a YouTube provocateur by posting white-power videos online, Covington decided to herd them into a single white-power army himself.

In a preview of 8Chan, the message-board website that would become a haven for white nationalists in the 2010s, he began bringing together various strains of supremacists, or as he put it, “normalizing relations.” His early attempts didn’t go well. The few Klan members he was able to woo were largely fabulists who made up stories to make themselves seem more violent than they really were. Deciding he needed to get a better cut, Covington organized a racist retreat on September 22 at a borrowed farm outside Louisburg, about 30 miles northeast of Raleigh, and sent word through the bars, garages and diners where “his people” hung out that they were all invited.

With the media dutifully attending what promised to be a freakshow, no detail was too small for Covington to stage-manage. Kids milled around a barbecue pit where a whole hog roasted, while parents doused a huge cross in kerosene. Nazis wore uniforms budgeted at $25 for tailored pants, $10 for boots and $2 for arm bands. The sound system alternated bluegrass tunes and “The Ride of the Valkyries.” A cute blonde in a “White Power” t-shirt sauntered with a Doberman and a rifle for photographers. In a crib, a baby wore a small shirt that read “Future Klansman.” For extra inspiration, a noose hung from a tree.

Late in the afternoon, a caravan of 20 Klansmen pulled into the farm led by a gaunt mechanic with a plunging jawline named Virgil Griffin. Griffin carried the title of Imperial Wizard of a backwoods klavern known as the Invisible Empire in Mount Holly, close to the South Carolina border. But he was also something of a joke on the national stage. His rallies, unlike Covington’s barbecue, were often threadbare affairs that dissolved into chaos. At one event, he’d been shouted down by protesters singing the theme song from “The Mickey Mouse Club,” according to an account from a community journalist, Elizabeth Wheaton, who covered radical politics around Greensboro.

If Covington looked in the mirror and saw a worldwide revolutionary, Griffin viewed himself as a backwoods patriot. After the China Grove debacle, he concluded that local Klans needed better leadership and more action, and believed he could provide both. Covington was only too happy to help feed such ambitions, elaborately making the Imperial Wizard feel like an honored guest among the other extremists—who also included the Klansmen who had peeled off from the Grady’s Federated Knights after China Grove, and a Nazi-curious crew from Winston-Salem.

“You take a man who fought in the Second World War, it’s hard for him to sit down in a room full of swastikas,” a Klansman told the Associated Press. ... “But people realize time is running out. We’re going to have to get together.”

The extremists nattered about where to buy guns and how to deal with the summer heat—Klan robes were sweatier than Nazi uniforms. And they found common ground.

“You take a man who fought in the Second World War, it’s hard for him to sit down in a room full of swastikas,” a Klansman told the Associated Press, which published a report about the event called “North Carolina United Racist Front Forms.” Then he added: “But people realize time is running out. We’re going to have to get together.”

***

What Virgil Griffin didn’t know was that one of his closest allies was keeping the cops informed about this new alliance.

Unlike the years after 9/11 when American law enforcement took its focus off white nationalism to fight Islamist terror, the 1960s and ’70s were a period of robust intelligence-gathering in the supremacist underground. One of North Carolina’s most charismatic Klansmen, a car salesman named Bob Jones who recruited 12,000 members to his state chapter, was undone by an aide whose information led to him being dragged before Congress and held in contempt. In the case of Griffin, law enforcement’s material came from a chain-smoking handyman named Eddie Dawson.

Born in New Jersey, Dawson cut an odd figure for a Southern Klansman. He spoke with a twitchy northern accent and had an uncanny resemblance to the Hollywood actor William Holden. Having drifted down to Greensboro in the early ’60s—a time when black activists were staging sit-ins at segregated lunch counters—he managed to get invited to a meeting of the Klan, and quickly established himself as an enthusiastic recruit. In one career-building episode, he took an armed joy ride through a poor black neighborhood that he peppered with rifle fire.

Dawson, however, blamed the KKK for letting him get sentenced to nine months in jail after he was convicted of assault with intent to kill for the joy ride. He was still bitter when an FBI agent approached him at a coffee shop after he got out in 1969, and offered to pay him $25 every time he told the Bureau about a Klan meeting. Dawson shook hands on the deal.

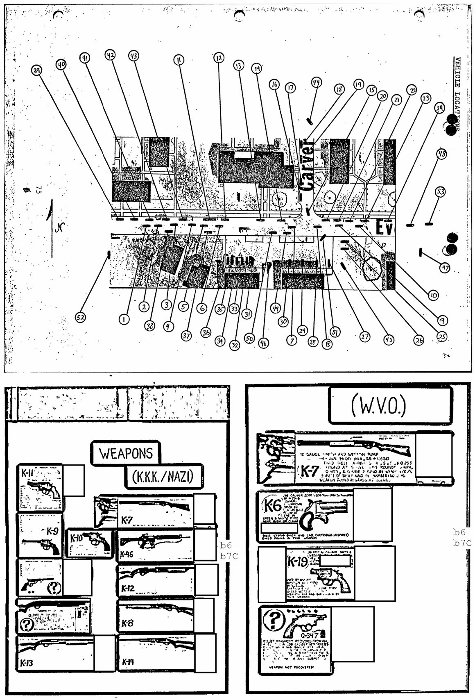

His time with the FBI ended the way most of his relationships did—unhappily. But Dawson resumed his double life a few weeks after Covington’s barbecue, when leaflets began appearing around Greensboro that announced a “Death to the Klan” march. The posters were the work of a group called the Workers Viewpoint Organization (WVO), which was filled with professionals who had elite-school degrees, identified as Maoists, and used revolutionary rhetoric to match. They had attempted to organize local textile workers, then tried direct action by taking part in the anti-KKK protest at China Grove. Now, they were itching for another, more visible confrontation with the Klan.

Greensboro History Museum // Politico

The leftists had plausible reasons for choosing to organize and demonstrate in North Carolina. At the end of the ’70s, the state ranked 49th in the U.S. in blue-collar wages and dead last in the percentage of workers who were unionized. But neither Duke educations nor medical training nor Maoist ideology prepared them to comprehend the culture of electricians, loggers or sheet-metal workers—jobs held by some of the men who would ride the caravan into Greensboro—beyond seeing them as either recruitable proletarians or irredeemable racists. The communists used language even more incendiary than the words on their flyers. On October 11, for instance, they issued a press release saying the KKK “must be physically beaten back, eradicated, exterminated, wiped off the face of the earth.” And they took exactly the wrong message from China Grove: that the Klan would be too cowardly to mount any resistance to them.

Instead, WVO’s leaflet lit a flame under Griffin and the Klan. It also alarmed the police in Greensboro. Soon, a detective who knew Dawson’s FBI past was talking with him about disrupting local meetings of communists, which made perfect sense. After all, the KKK rated communists about the same as black people. But Dawson had another angle, too: He could help the police investigate the Klan. With a highly-developed sense of grievance that often left him feeling under-appreciated and under-used, he saw a chance to become the one who was pulling the strings—both as an informant and as an instigator—as confrontations heated up.

On Saturday, October 20, when Griffin marched his Invisible Empire through the fairgrounds in Lincoln County, about 100 miles southwest of Greensboro, and told a crowd of 150 that if they cared about their children, they would “kill a hundred niggers and leave them dead in the street.” At a members-only meeting afterward, he introduced Dawson to talk about the planned WVO march. Towering over the 5-foot-6 Griffin, Dawson started out by warning that the communists were recruiting busloads of black college students to flood into Greensboro. Asked whether it would be a good idea to bring guns, he demurred. “I’m not your father,” he replied. “But if you carry a gun, you better have damned bond money.”

The vote among those in the audience was unanimous: They’d go to Greensboro to make their presence felt. The following weekend, as word spread, white supremacist groups met in at least three different locations around North Carolina and agreed to head there, too.

Dawson earned $50 by telling the Greensboro PD about the October 20 meeting. And he let them know Griffin was planning to come to town and looking for allies. But Dawson neglected to mention his own starring role, or the fact he subsequently drove around Morningside Homes in his Cadillac late at night, pasting leaflets over the “Death to the Klan!” posters. His replacements featured a dark figure hanging from a noose and the phrase, “It’s time for some old-fashioned American Justice.”

The Nazi camp, meanwhile, was getting just as frothy. At a November 1 event that Covington staged for the media in the garage of a sheet-metal worker named Roland Wayne Wood, a dozen of his recruits mugged through a made-for-TV roast of the disgraced China Grove wizard, Joe Grady.

Once the cameras departed, the united racists got down to the business of how they planned to crash the communists’ party in Greensboro. One suggested throwing eggs. Another went further, saying he had a pipe bomb that would be effective if thrown into a crowd. At 11:00 p.m., the group gathered around a television to watch themselves on the local news, only to become infuriated when a press conference held by the WVO’s members got more airtime. As the screen showed one of the march leaders calling the KKK “scum,” Jerry Paul Smith, the Klansman with the pipe bomb, took his gun and pointed it at the TV.

Police reports would later quote Wood as saying that he heard Smith mutter, “Kill the communist.”

***

On the morning of November 3, Dawson called his Greensboro Police contact to say that three dozen supremacists from around the state, including Virgil Griffin, were assembling at a house owned by one of Dawson’s Klan pals, a few miles from the Morningside Homes march site.

A little later, Dawson called again to warn that the place was chock full of firearms. But that information never made its way to the shift commander, who wrapped up a daily briefing at about 10:30 that morning by reminding his men the parade permit listed a start time of noon. The officers could get breakfast, he said, so long as they were on the route by 11:30.

Greensboro News and Record // Politico

As the Klansmen and Nazis made their way along Interstate 85 into Greensboro, a Greensboro Police detective spotted the caravan and called in to ask if tactical units were in place. His supervisor, showing no special concern, replied that there was still “another fourteen minutes by my watch” for breakfast.

The leftists planned to line up their crew at 11:00, then begin marching at noon. But at 11:22, a frightening transmission came over a CB radio: Klansmen were talking about closing in. Before the protesters could react, cars with Confederate-flag license plates began approaching. There were no cops in sight.

Dawson, who was leading the convoy, would later tell police and reporters that he merely wanted to put a scare into the Maoists before driving on to the spot at the shopping center where the march would end. It was Dawson who yelled, “You asked for the Klan. Now you got ’em!”

But then Griffin’s white LTD screeched and swerved, nearly hitting a marcher. The caravan came to a stop. The communists went from singing to swinging, banging their placards on the cars. Members of the convoy poured out, punching through the melee, grabbing weapons. Dawson told his driver to get the hell out of there—and since they were in the first car of the caravan, they were able to split.

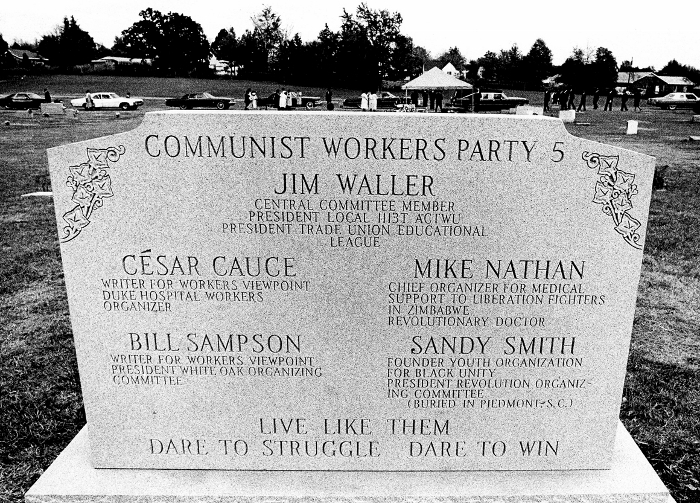

The WVO had packed a few weapons, but were seriously outgunned. One of the WVO leaders, a physician named Jim Waller, lunged for a 12-gauge shotgun he’d stashed in a car, but a Klansman flew toward him before he could fire. The two rolled in the grass, fighting nose-to-nose over the weapon until others started piling on top of them and the pump mechanism snapped. Waller screamed as the pump-action crushed the bones in his shooting hand.

Greensboro News and Record // Politico

Amidst the chaos, other white supremacists lined up their shots. A Nazi named Jack Fowler opened the trunk of a blue Ford Fairlane and, with a cigarette hanging from his mouth, handed out rifles and shotguns. David Matthews, from Griffin’s Klan, stood behind the door of a van and nailed his first target, a bookish pediatrician named Mike Nathan. Then Matthews took down an organizer named Jim Wrenn, who was crawling on his belly. Bill Sampson, a former Harvard Divinity student, tried to give Wrenn rifle cover but took two fatal shots in the heart.

Roland Wayne Wood observed Waller writhing from his crushed hand. Coolly aiming his shotgun, the Nazi delivered a blast into the physician’s right side. Matthews, the Klan member, finished the job with another blast into Waller’s back.

The convoy sped away, with Matthews’ van the last to leave the scene. Climbing aboard, Matthews let the rest of squad know: “I got three of ’em.” Moments later, police intercepted the van, but didn’t get to Morningside Homes until the shooting was over.

***

Eighty-eight seconds of gunfire in Greensboro marked the worst violence in the South since the 1960s. And for the men who shot their enemies dead, November 3, 1979, was just the beginning of a new era of notoriety and collaboration. The botched trials and political response that followed ensured that white nationalism would grow to become more dangerous than ever today.

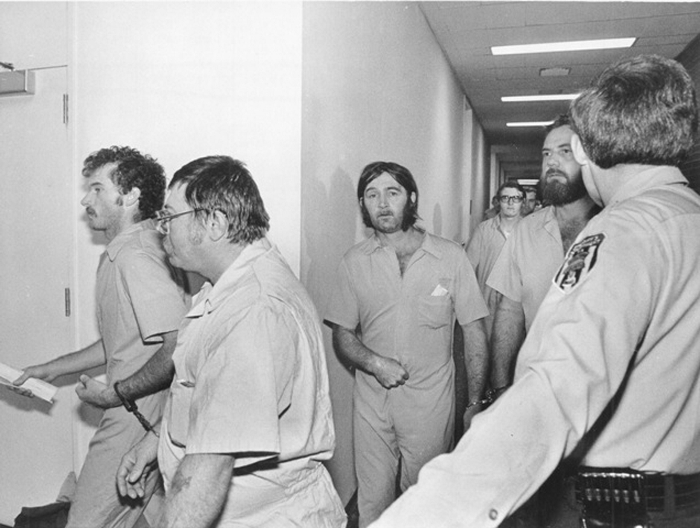

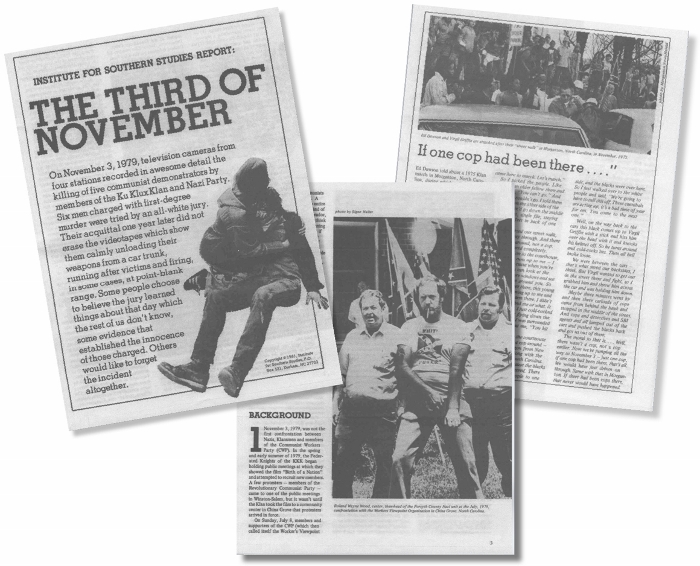

The legal system took three whacks at the Greensboro conspirators. First, police rounded up 14 Klansmen and Nazis, and the state of North Carolina charged most of them with first-degree murder and felony riot. Prosecutors lined up eyewitnesses, videotapes, weapons and FBI ballistics analysis. But they couldn’t convince the surviving revolutionaries—who were stubbornly convinced the cops had conspired to leave them unprotected—to cooperate.

Greensboro News and Record // Politico

At trial, the Klansmen and Nazis wrapped themselves in the American flag and argued self-defense. “They acted like men to aid someone in distress,” Wood’s lawyer claimed. “They would not have been worthy of anyone’s respect if they had done otherwise.” He added that his client just wanted to sing, “My country ’tis of thee, sweet land of liberty, from every mountainside, let freedom ring.”

On November 17, 1980, an all-white jury found the Klansmen and Nazis not guilty. “Anytime you defeat communism,” said Jerry Pridmore, one of the men acquitted, “it’s a victory for America.”

The U.S. Justice Department then charged nine Klansmen and Nazis, this time including Griffin and Dawson, with conspiracy to violate the civil rights of the Greensboro victims. In April 1984, the federal jury, also all-white, refused to conclude the defendants had violated the law by acting out of racial rather than political hatred. It too delivered not-guilty verdicts across the board.

Clippings from the 1981 Institute for Southern Studies Report // Politico

Finally, the victims filed a $48-million lawsuit against 87 defendants, including the city of Greensboro, the state of North Carolina, the Justice Department and the FBI. Wood, now on trial for the third time, felt confident enough to give a Nazi salute when sworn to testify.

In June 1985, the civil jury delivered a landmark yet twisted verdict: They found eight defendants liable for wrongful death: Dawson, five Klan and Nazi shooters, the Greensboro police detective who received advance word about the attack from Dawson and the lieutenant who was the GPD event commander at the massacre. But the jury applied that decision only in the case of Michael Nathan, the one murder victim who wasn’t a WVO member at the time of the shootings. To avoid appeals, the city of Greensboro settled for $351,000, sending a check to Nathan’s widow, who split it among the survivors.

Strike three.

The supremacists who emerged from the Greensboro trials understood they were free. Free not just to stay out of prison, or to keep burning rags and kvetching about the price of jackboots. Free to work together to stockpile weapons, terrorize neighborhoods and commit violence up to and including murder—so long as their opponents were communists.

courtesy of authors // Politico

“The Klan and Nazis felt emboldened,” says Patricia Clark, a veteran Klan watcher who served on the Greensboro Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which local citizens set up in the mid-2000s to investigate the massacre. “They thought they won the fight.”

By 1980, membership in Klan-Nazi fusion groups began to outnumber that of old-school Klans. And as horizons of hate broadened and merged, alliances deepened around the country. As just one example, four months after Greensboro, the California Knights of the Ku Klux Klan rallied in the city of Oceanside and beat counter-protesters with baseball bats. The marchers brayed a version of “Sixteen Tons,” the old coal-mining song. Their rewritten lyrics celebrated the Greensboro killings and ended, “If the Nazis don’t get you, a Klansman will.”

The increasing unity of far-right factions was more than tactical. By transfusing “blood and soil” into American racism, it led to what historian John Drabble called in a 2007 study “the Nazification of the Ku Klux Klan.” That was bad news for hustlers like Eddie Dawson. Dawson managed to dodge Klan retribution for informing. But he soon found it much harder to profit from playing different extremists against one another. Greensboro turned Dawson into a relic—and the hardening ideology of right-wing terror networks that followed made them harder for the FBI to penetrate.

Meanwhile, new doors swung wide open for fanatics like Frazier Glenn Miller, a Covington acolyte and former Green Beret who rode in the Greensboro caravan. Miller founded the Carolina Knights of the Ku Klux Klan in 1980. And by merging Klan and Nazi symbolism while instilling paramilitary discipline in his followers, he quickly built the strongest white-power group in the state.

As an emboldened white-power movement spread, Miller connected its dots. The Greensboro veteran held public marches, harassed local black residents and amassed huge caches of explosives. In 1987, he issued a revolutionary “Declaration of War” filled with calls for assassinations. He coordinated with The Order, a violent extremist group inspired by The Turner Diaries. And he sought allies through voluminous racist literature and eventually on the Internet, where he extolled the mass shooting by Anders Behring Breivik in Norway. Miller returned to racist murder in 2014, when he targeted a Jewish community center in Overland Park, Kansas, and killed three people. That landed him on death row, where he sits today.

Greensboro’s aftershocks held their most important lessons for mainstream opportunists. By the end of the 1970s, southern nationalists had spent more than a decade trying to re-code their racism to make it more palatable. As master political consultant Lee Atwater put it: “You start out in 1954 by saying, ‘Nigger, nigger, nigger.’ By 1968, you can’t say ‘nigger’—that hurts you, backfires. So you say stuff like forced busing, states’ rights.”

Republican politicians soon realized they could go even farther. After Greensboro, it became clear that, as historian Kathleen Belew has written, extremists “increasingly used anticommunism as an alibi for racial violence.” And by targeting the far right’s dual paranoias—federal authority and socialism—GOP operatives were able to harness its nativism while hanging onto the votes of establishment conservatives.

Over the next 30 years, Republicans racked up spectacular gains in state legislative seats, governorships and U.S. Senate elections across the South by hammering cultural issues that the far right recognized as approving winks. A decade after Greensboro, establishment candidates were already posing in front of rebel flags and openly courting “white heritage” groups like the United Daughters of the Confederacy. The GOP advanced most in counties where the Klan had been active in the ’60s, according to a 2014 study by political scientists from Notre Dame, Brandeis and Yale.

During the administration of President Barack Obama, the new generation of conservative politicians had the extremists’ backs. In 2009, the Department of Homeland Security issued a report forecasting a rise in racist violence. Republicans objected so vociferously that DHS rescinded the projection and silenced its domestic terrorism unit. Mike Pompeo, then a congressman from Kansas, said it was “dangerous” to track homegrown violence.

By that point it was hard to tell who was co-opting whom on the right. Republicans were playing to the fringe without worrying where their most incitable elements might channel their anger.

Greensboro News and Record // Politico

And you know what happened next: Jonah turned the whale inside out. Donald Trump’s bald invocations of racial and working-class grievances made him a hero to the ultras; “MAGA” is the most common word in Twitter user profiles among members of the alt-right, according to a study by J.M Berger of the research network VOX-Pol. From Charlottesville to Pittsburgh to El Paso, right-wing attacks have surged. The latest evidence: The FBI made almost 100 arrests related to domestic terrorism by July of this year, more than in all of 2018, according to agency director Christopher Wray, who told Congress the majority of cases involved “white supremacist violence.”

In Greensboro, private citizens tried to find a way forward by empaneling a Truth & Reconciliation Commission—the first in U.S. history. But today’s political landscape, where the language and resentments of white nationalism have taken deeper root than ever, raises the question: What happens when there is no reconciliation in truth?

Twenty-six years after the massacre, Virgil Griffin surprised everyone at the Greensboro Commission by showing up and taking questions.

Asked why no Klansman was killed in the shootings, he answered: “Maybe God guided the bullets.”

[Shaun Assael is a New York Times-bestselling author. He can be seen in a documentary based on his latest book, The Murder of Sonny Liston, at 9 p.m. on Nov. 15 on Showtime.

Peter Keating is an investigative writer in Montclair, N.J.]

Spread the word