Philip C. Kolin has published extensively in Black history and literature, especially the surreal plays of Adrienne Kennedy (he published the first book on her canon) and Suzanne-Lori Parks that expose the horror of racism in America from the slave ships to Jim Crow discrimination. He has also published several collections of poetry dealing with racism in America, most notably Emmett Till in Different States and Delta Tears, both of which might well form a trilogy with his new and powerful book of resistance poems, White Terror, Black Trauma, published by Third World Press, the oldest independent press in America devoted to Black thought and the arts.

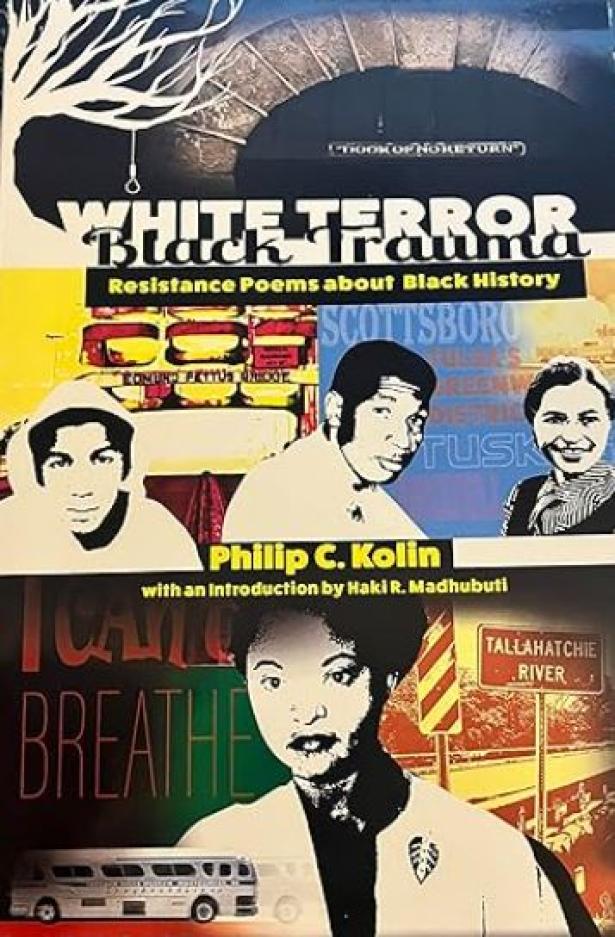

White Terror; Black Trauma: Resistance Poems about Black History

By Philip C. Kolin

Third World Press; 72 pages

October 28, 2023

Paperback: $19.95

ISBN-10 : 0883784270

ISBN-13 : 978-0883784273

The poems in this collection are arranged chronologically, from the arrival of the first enslaved Africans in "Jamestown, birthplace / of a nation, blackened by our moans," in the opening poem, "1619" (1), to the contemporary horrors that have befallen victims including George Floyd and Ahmaud Arbery, both of whom are also commemorated within this collection.

Kolin also honors the memories of those who fought against racism in America, such as the freedman Denmark Vesey, who led an 1822 slave rebellion "... against what his own white-given name / condemned him to-being owned by another..." (3). Each poem in the collection carries a helpful headnote identifying key individuals, places, and times. For instance, the preamble to "Denmark Vesey" clarifies that Vesey "was a member of the AME Mother Emanuel Church where Dylann Roof murdered so many parishioners in 2015" (3). In addition to providing context, this headnote reveals one of the recurring themes of the collection: the ways in which the scars caused by slavery and other forms of racial violence in America linger, influencing and echoing future events within a chronology of traumas. Similarly, "1619" allows its enslaved narrators to peer forward through time to decry the fact that their

...legacy hardly acknowledged

even when Queen Elizabeth II came

to celebrate the three hundred and fiftieth

anniversary of this settlement. (1)

In lines such as these, Kolin engages in one of the most valuable and necessary tasks of resistance poetry: to reveal the struggles of men and women whose voices have been overlooked or buried in some cases intentionally by history.

As Kolin moves through America's Civil War era, he focuses on examples of Black heroism. In poems such as "A Black Woman Called Moses" and "Ain't I a Woman," Kolin highlights the work of abolitionists Harriet Tubman and Sojourner Truth, and the poem "Dred is Still not Free" recounts the struggles of Dred Scott, who was declared "Once a slave, always a slave" by "Chief Injustice" Roger Taney. Kolin sees the story of Dred Scott as the preamble to a Civil War "that continued for over 150 years-/Jim Crow was a part of Dred's legacy" (8). In poems such as "Remember Fort Pillow," he paints in powerful and vivid verse the less- studied sacrifice of Black soldiers such as the Colored Light Infantry:

They wore Union blue, all 300 souls of the

Colored Light Infantry stationed at Fort Pillow on

a bluff that overlooks the Mississippi where it

snakes around a bend and flows down to

Memphis.

Ditches, trenches, bunkers and parapets could not protect them from

rebel snipers and artillerymen, Some 2,500

strong, who stormed the Fort in savage fury.

Bedford Forrest's marauders took no Black

prisoners.

They saw only slaves who had fled the Stars and Bars And massacred

them, even when they tried to surrender Or escape,

hiding in cuts and hollows, or running

Down to the river. Their blood turned the Mississippi red.

Eyes and bowels ripped open, brains scattered, their bodies

Burnt to embers, a warning to those who chose to wear Union

blue rather than chains. No comfort, no soldiers' rights. They

say their ghosts still haunt this section of the river

Wearing campaign medals bright shining as the sun.

(10)

From here, Kolin continues into the painful decades of Reconstruction and Jim Crow, a time of lynchings and bloodshed. Here, Kolin exemplifies the important role resistance poetry plays in revealing the trauma wrought by injustice. "L is for Louisiana" and "Knots" describe, respectively, an 1886 lynching in Shreveport, Louisiana, and a 1902 lynching in Bolivar County, Mississippi. "Triple Lynched" tells the tragic story of Mary Turner, who

...was only 20, a baby in her womb for 8 months, when a crazed white

mob from Lowndes County taught

her a lesson for defending her

husband on a false murder charge...

(17)

Kolin also explores a series of 1919 race riots, including the "Massacre at Elaine"; the 1921 destruction of Black Wall Street in Oklahoma ("Kristallnacht in Tulsa"); the destruction of the Black town of Rosewood, Florida in 1923 (“A Town Called Rosewood"); the 1931 sham trial of nine Black teenagers

in Alabama convicted by an all-white jury of raping two white women ("Scottsboro Justice"); and the Tuskegee syphilis experiment, which occurred over four decades from 1932 to 1972 ("Tuskegee's Bad Blood"). Of particular note here is the poem "America's Largest Black Morgue." In haunting verse, this poem pays homage to the countless Black bodies that have been consigned to rivers over the three centuries of America's history:

The river craves Black bodies- plunging them into liquid darkness.

While river ravens and cormorants

hunger to be pallbearers of the

air,

America's largest Black morgue is the river bottom.

Shifting mud an icon for flesh, Black bodies constantly

changing

even after death. Skeletons

amputated by foul tides and

paddlewheelers.

Fish flap inside and then outside

Klan-burned cars while gar glide in

and out of refrigerator coffins.

Tin roofs search for bombed houses.

Old Black men in muddy frockcoats and neckties made from

lynching rope

surface on moonless nights,

congregating on

dissolving

levees

proclaiming—

"There is no more deep to call.”

(29)

he last third of the collection reveals that stories of white terror and Black trauma remain all too common in the present day. Here, Kolin recounts numerous stories, almost all from the past two decades, of police violence against Black men and women. "The Hoodie" examines the killing of Trayvon Martin by George Zimmerman in 2012. Two years later, "I Can't Breathe" became a rallying cry after the killing of Eric Garner by police officer Daniel Pantaleo on Staten Island. "The Ferguson Riots" examines the yearlong protests following the shooting of Michael Brown by police officer Darren Wilson on August 9, 2014. "Palm Trees Didn't Grow that Year in Cleveland" tells the story of 12-year-old Tamir Rice, who was shot by a cop while holding a toy gun. The murder of Ahmaud Arbery is the subject of "2.23," and the brutal killing of George Floyd, which sparked off a summer of fiery protests in 2020, is the focus of "Golgotha Outside Cups." The final poem in the collection, "What Did I Do," captures the killing of Tyre Nichols, who was brutalized by a special unit of cops called the Scorpions. These stories reveal another important purpose of resistance poetry. When the institutions of the nation itself are complicit in the violence, the role of the resistance poet is to ensure that the crimes of the powerful do not remain hidden.

The penultimate poem in the collection, "Emmitt Till on America's Streets Today," revisits one of Kolin's frequent subjects, casting the fourteen-year-old Till, who was brutally murdered while visiting family in Mississippi, as a synecdochic representative of the countless Black Americans killed throughout our nation's bloody history:

Emmett is buried in so many

memories both living and deceased, all

devoted to enshrining his suffering in a

history that continues on American streets.

Mamie cradles her son weighed down by all that white lie

testimony given by

Sheriff Strider

and the deputized

fury

of Money,

Mississippi

still loose on America's streets.

Emmett has become

the patron saint

of all those Black bodies

shot apart

in routine traffic stops.

He sobs breathlessly

for all those driving while Black.

(70)

Though Till's brutal murder happened almost seventy years ago, it could be mistaken for another of the present-day stories of violent injustice recounted in the poems preceding and following it. Thus, again, Kolin reveals the uncomfortable ways in which the stories in America's chronology of Black trauma echo and, if allowed to be forgotten, repeat themselves.

While no poetry collection can fully catalog the entire history of wrongs levied against Black Americans, White Terror, Black Trauma offers a chilling and emotional exploration of that history's trajectory, from the first slaves to arrive in the Colonies to the most recent brutalities. In these resistance poems of witness, readers can see how their various subjects create a roadmap of the nation's racial scars, remnants of the harms done to Black Americans by a country that has too often made itself complicit in their suffering.

[Billy Middleton teaches first-year writing, fiction writing, and film studies at Stevens Institute of Technology in Hoboken, New Jersey. His scholarly and creative work has also appeared in CRAFT Literary, J Journal, and The Southern Quarterly, among other places.]

Spread the word