In September 1963, in Llansteffan, Wales, a stained-glass artist named John Petts was listening to the radio when he heard the news that four black girls had been murdered in a bombing while at Sunday school at the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama.

The news moved Petts, who was white and British, deeply. “Naturally, as a father, I was horrified by the death of the children,” said Petts, in a recording archived by London’s Imperial War Museum. “As a craftsman in a meticulous craft, I was horrified by the smashing of all those windows. And I thought to myself, my word, what can we do about this?”

Petts decided to employ his skills as an artist in an act of solidarity. “An idea doesn’t exist unless you do something about it,” he said. “Thought has no real living meaning unless it’s followed by action of some kind.”

With the help of the editor of Wales’s leading newspaper, the Western Mail, he launched an appeal for funds to replace the Alabama church’s stained-glass window. “I’m going to ask no one to give more than half a crown,” he told Petts. “We don’t want some rich man as a gesture paying for the whole window. We want it to be given by the people of Wales.”

Two years later, the church installed Petts’ window, flecked with shades of blue, featuring a black Christ, his head bowed and arms splayed above him as though on a crucifix, suspended over the words “You do it to me” (inspired by Matthew 25:40: “Truly, I say to you, as you did it to one of the least of these my brothers, you did it to me”).

Photograph: National Geographic Image Collection/Alamy Stock Photo // The Guardian

Europe’s identification with black America, particularly during times of crisis, resistance and trauma, has a long and complex history. It is fuelled in no small part by traditions of internationalism and anti-racism on the European left, where the likes of Paul Robeson, Richard Wright and Audre Lorde would find an ideological – and, at times, literal – home.

“From a very early age, my family had supported Martin Luther King and civil rights,” the Northern Irish Catholic author and screenwriter Ronan Bennett, who was wrongfully imprisoned by the British in the infamous Long Kesh prison in Northern Ireland in the early 70s, told me. “We had this instinctive sympathy with black Americans. A lot of the iconography, and even the anthems, like We Shall Overcome, were taken from black America. By about 71 or 72, I was more interested in Bobby Seale and Eldridge Cleaver [of the Black Panthers] than Martin Luther King.”

But this tradition of political identification with black America also leaves significant space for the European continent’s inferiority complex, as it seeks to shroud its relative military and economic weakness in relation to America with a moral confidence that conveniently ignores both its colonial past and its own racist present.

A public inquiry into the racist murder of British teenager Stephen Lawrence was taking place in 1998 when news reached Britain of the plight of James Byrd, a 49-year-old African American man, who was picked up by three men in Jasper, Texas. They assaulted him, urinated on him, chained him to their pickup truck by his ankles and dragged him more than a mile until his head came off. During an editorial meeting at the Guardian, where I was then working, one of my colleagues remarked of Byrd’s killing: “Well, at least we don’t do that here.”

In the years since then, the number of Europeans of colour – particularly in the cities of Britain, the Netherlands, France, Belgium, Portugal and Italy – has grown considerably. They are either the descendants of former colonies (“We are here because you were there”) or the more recent immigrants who may be asylum seekers, refugees or economic migrants. These communities, too, seek to pollinate their own, local struggles for racial justice with the more visible interventions taking place in the US.

“The American Negro has no conception of the hundreds of millions of other non-whites’ concern for him,” Malcolm X observed in his autobiography. “He has no conception of their feeling of brotherhood for and with him.”

Over the past week, huge crowds have gathered across Europe to express their solidarity with the rebellions against police brutality sparked by the murder of George Floyd. (Women’s plight is less likely to make it across the Atlantic. The name of Breonna Taylor, prominent in the US protests, is less in evidence here.) The air in central Paris was heavy with smoke and teargas as thousands of protesters took a knee and raised a fist. In Ghent, a statue of Leopold II, the Belgian king who pillaged and looted the Congo, was covered in a hood with the caption “I Can’t Breathe” and splashed with red paint. In Copenhagen, they chanted “no justice, no peace”. There were scuffles in Stockholm; Labour-controlled councils in municipalities across Britain were lit purple in solidarity; US embassies and consulates from Milan (where there was a flashmob) to Krakow (where they lit candles) were a focus of protest, while tens of thousands of marchers, from London’s Trafalgar Square to The Hague, from Dublin to Berlin’s Brandenburg Gate, violated social-distancing orders to make their voices heard.

Photograph: Mohammed Badra/EPA // The Guardian

While not new, these transnational protests have become more frequent now because of social media. Images and videos of police brutality and the mass demonstrations in response, distributed through diasporas and beyond, can energise and galvanise large numbers quickly. The pace at which these connections can be made and amplified has been boosted, just as the extent of their appeal has broadened. Trayvon Martin was a household name in Europe in a way that Emmett Till never has been.

Some of this is simply a reflection of American power. Political developments in the US have a significant impact on the rest of the world – economically, environmentally and militarily. Culturally, the US has a heft unlike any other nation’s, and that influence extends to African Americans. Well into my 30s, I was far more knowledgeable about the literature and history of black America than I was about that of black Britain, where I was born and raised, or indeed of the Caribbean, where my parents are from. Black America has a hegemonic authority in the black diaspora because, marginalised though it has been within the US, it has a reach that no other black minority can match.

And so, across Europe, we know the names of Trayvon Martin, Michael Brown and George Floyd. Whereas Jerry Masslo, who escaped apartheid South Africa only to be murdered by racists near Naples in 1989, prompting the first major law in Italy legalising the status of immigrants, is barely known outside that country. Likewise, the story of Benjamin Hermansen, the 15-year-old Norwegian-Ghanaian boy who was murdered by neo-Nazis in Oslo in 2001, setting off huge demonstrations and a national anti-racism prize, is rarely told beyond Norway. (Although, through a quirk of acquaintance, Michael Jackson dedicated his 2001 album Invincible to Benjamin, but I doubt even his most devoted fans would get the reference.)

The interest is not mutual. While the comparison between Stephen Lawrence and James Byrd in that Guardian conference was awkward, at least it was possible; it is unlikely that anyone in most American newsrooms would have heard of Lawrence. This is not the product of callous indifference, but the power of empire. The closer you are to the centre, the less you need know about the periphery, and vice versa.

From the vantage point of a continent that both resents and covets American power, and is in no position to do anything about it, African Americans represent to many Europeans a redemptive force: the living proof that the US is not all it claims to be, and that it could be so much greater than it is. That theme gives the lie to the lazy, conservative slur that the European left is fundamentally anti-American. The same liberals who reviled George W Bush went on to love Barack Obama; the same leftists who excoriated Richard Nixon embraced Muhammad Ali, Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr. Even as the French decried the “Coca-Colonisation” of cultural imperialism that began with the Marshall Plan, they welcomed James Baldwin and Richard Wright. In other words, the rejection of US foreign policy and power – at times reflexive and crude, but rarely completely unjustified – never entailed a wholescale repudiation of American culture or potential.

And in times when the US valued its soft power, it cared about how it was perceived elsewhere. “ issue of race relations deeply affects the conduct of our foreign policy relations,” said secretary of state Dean Rusk in 1963. “I am speaking of the problem of discrimination … Our voice is muted, our friends are embarrassed our enemies are gleeful … We are running this race with one of our legs in a cast.”

Now is not one of those times. George Floyd’s killing comes at a moment when the US’s standing in Europe has never been lower. With his bigotry, misogyny, xenophobia, ignorance, vanity, venality, bullishness and bluster, Donald Trump epitomises everything most Europeans loathe about the worst aspects of American power. The day after Trump’s inauguration, there were women’s marches in 84 countries; and today, his arrival in most European capitals provokes huge protests. By his behaviour at international meetings, and his resolve to pull out of the World Health Organization in the middle of a pandemic, he has made his contempt for the rest of the world clear. And, for the most part, it is warmly reciprocated.

Photograph: Emerson Utracik/REX/Shutterstock // The Guardian

Although police killings are a constant, gruesome feature of American life, to many Europeans this particular murder stands as confirmation of the injustices of this broader political period. It illustrates a resurgence of white, nativist violence blessed with the power of the state and emboldened from the highest office. It exemplifies a democracy in crisis, with security forces running amok and terrorising their own citizens. The killing of George Floyd stands not just as a murder, but as a metaphor.

Those pathologies did not come from nowhere. “No African came in freedom to the shores of the New World,” wrote the 19th-century French intellectual Alexis de Tocqueville. “The Negro transmits to his descendants at birth the external mark of his ignominy. The law can abolish servitude, but only God can obliterate its traces.” That “mark” serves as a ticket to a world that seeks to understand black America as from, but not entirely of, the US – simultaneously central to a version of its culture and absolved from consequences of its power.

This perception of black America was often patronising or infantilising. “If I were an elderly Negro,” wrote the fledgling Soviet Union’s most celebrated poet, Vladimir Mayakovsky, in his 1927 poem To Our Youth, “I would learn Russian, / without being despondent or lazy, just because Lenin spoke it.” (As for Lenin, his favourite book as a child was Uncle Tom’s Cabin.) Europe’s exoticisation of Josephine Baker in the Revue nègre was no one-off, even if Baker herself was unique. In the late 60s, the West German media described the activist Angela Davis as “the militant Madonna with the Afro-look” and “the black woman with the ‘bush hairdo’.” In East Germany, they referred to her as: “The beautiful, dark-skinned woman captured the attention of the Berliners with her wide, curly hairstyle in the Afrika-Look.”

But, for all that it was flawed, the admiration in the connection was nonetheless genuine. There has always been a strong internationalist current of anti-racism, alongside anti-fascism, in the European left tradition, which provided fertile ground for the struggles of African Americans. Back in the 1860s, Lancashire mill workers, despite being impoverished themselves by the blockade on Confederacy that caused the supply of cotton to dry up, resisted calls to end the boycott of Southern goods, though it cost them their livelihoods. In the early 1970s, the Free Angela Davis campaign told the New York Times that it had received 100,000 letters of support from East Germany alone – too many even to open.

If Europe has a proven talent for anti-racist solidarity with black America, one that has once again come to the fore with the uprisings in the US, it also has a history of exporting racism around the world. De Tocqueville was right to point out that “No African came in freedom to the shores of the New World,” but he neglected to make clear that it was primarily the “Old World” that brought those Africans there. Europe has every bit as vile a history of racism as the Americas – indeed, the histories are entwined. The most pertinent difference between Europe and the US in this regard is simply that Europe practised its most egregious forms of anti-black racism – slavery, colonialism, segregation – outside its borders. America internalised those things.

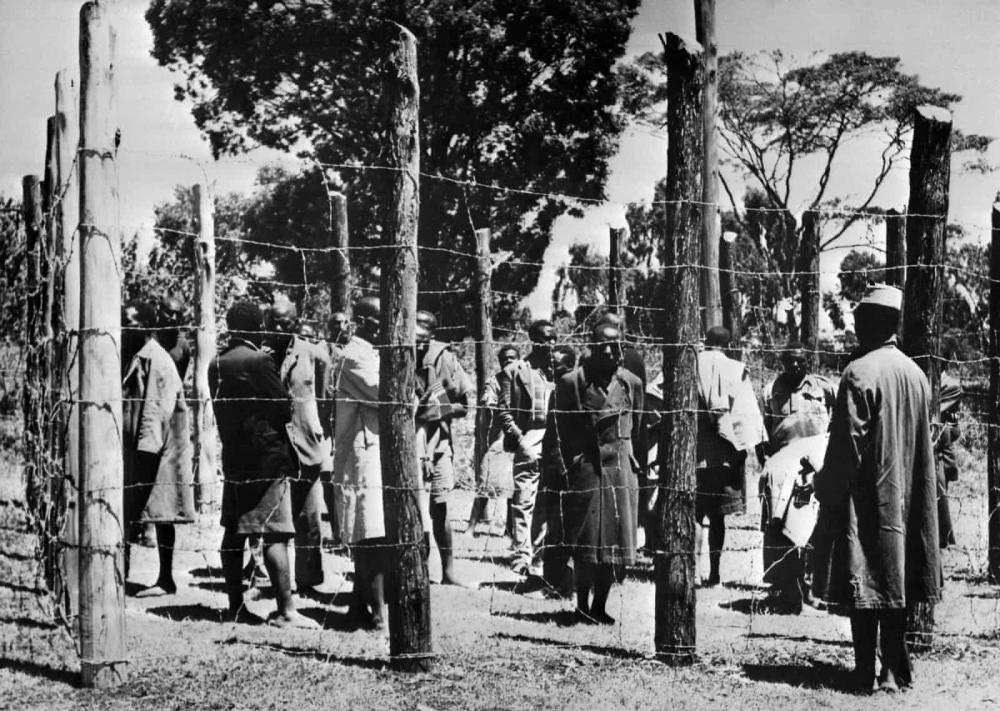

In the time that elapsed between Petts hearing about the Birmingham bombing and the stained-glass window being installed in Alabama, six African countries liberated themselves from British rule (and there would be more to come), while Portugal hung on to its foreign possessions for another nine years. If Petts had been in search of a heart-rending story thousands of miles from home in the previous years, he could have looked to Kenya, where his own government was torturing and murdering thousands in response to a revolt for freedom.

One of the central distinctions between the racial histories of Europe and the US is that, until relatively recently, the European repression and resistance took place primarily abroad. Our civil rights movement was in Jamaica, Ghana, India and so on. In the post-colonial era, this offshoring of responsibility has left significant room for denial, distortion, ignorance and sophistry when it comes to understanding that history.

“It is quite true that the English are hypocritical about their Empire,” wrote George Orwell in England Your England. “In the working class this hypocrisy takes the form of not knowing that the Empire exists.” In 1951, a decade after that essay was published, the UK government’s social survey revealed that nearly three-fifths of respondents could not name a single British colony.

Photograph: -/AFP/Getty Images // The Guardian

Such selective amnesia about their own imperial legacy leads ineluctably to a false sense of superiority around racism among many white Europeans toward the US. Worse is the toxic nostalgia that to this day taints their misunderstanding of that history. One in two Dutch people, one in three of Britons, one in four of the French and Belgians, and one in five Italians believe that their country’s former empire is something to be proud of, according to a YouGov poll from March of this year. Conversely, only one in 20 Dutch, one in seven French, one in five Britons, and one in four Belgians and Italians regard their former empires as something to be ashamed of. These are all nations that saw large demonstrations in solidarity with the George Floyd protests in the US.

Their indignation all too often bears insufficient self-awareness to see what most of the rest of the world has seen. They wonder, in all sincerity, how the US could have arrived at such a brutal place – with no recognition or regret that they have travelled a similar path themselves. The level of understanding about race and racism among white Europeans, even those who would consider themselves sympathetic, cultured and informed, is woefully low.

The late Maya Angelou recognised this gulf between what her own relationship to France was compared with France’s relationship to others who looked like her. That realisation was what made her decide, while on tour with Porgy and Bess in 1954, not to follow the familiar path of black artists and musicians who had settled there.

“Paris was not the place for me or my son,” she concluded in Singin’ and Swingin’ and Gettin’ Merry Like Christmas, the third volume of her autobiography. “The French could entertain the idea of me because they were not immersed in guilt about a mutual history – just as white Americans found it easier to accept Africans, Cubans or South American blacks than the blacks who had lived with them foot to neck for 200 years. I saw no benefit in exchanging one kind of prejudice for another.”

And that brings us to the other problem with Europe’s credibility on this score: namely, the prevalence of racism in Europe today. Fascism is once again a mainstream ideology on the continent, with openly racist parties a central feature of the landscape, framing policy and debate even when they are not in power. There are no viral videos of refugees in their last desperate moments, struggling for breath before plunging into the Mediterranean (possibly headed to a country, Italy, that levies fines on anyone who does rescue them). Only when, in 2015, a three-year-old Syrian boy, Alan Kurdi, was washed up dead on a Turkish beach, did we see in Europe an effect like that to the American videos of police shootings: painful proof of the inhumanity in which our political cultures are similarly complicit.

Levels of incarceration, unemployment, deprivation and poverty are all higher for black Europeans. Perhaps only because the continent is not blighted by the gun culture of the US, racism here is less lethal. But it is just as prevalent in other ways. Racial disparities in Covid-19 mortality in Britain, for example, are comparable to those in the US. Between 2005 and 2015, there were race-related riots or rebellions in Britain, Italy, Belgium, France and Bulgaria. The precariousness of black life in late capitalism is not unique to the US, even if it is most often and glaringly laid bare there. To that extent, Black Lives Matter exists as a floating signifier that can find a home in most European cities, and beyond.

So, given all of that, with what authority do Europeans get to challenge the US over racism? This is a question that black European activists constantly seek to triangulate, using the attention focused on the situation in the US to force a reckoning with the racism in their own countries. There is no reason, of course, why the existence of racism in one place should deny one the right to talk about racism in another place. (If that were the case, the anti-apartheid movement would never have got off the ground in the west.) But it does mean having to be mindful about how one does it. I have seen many instances of black activists here trying to turn Europe’s wider cultural obsession with the US’s bigger canvas to their advantage and educate their own political establishments about the racism on their doorstep. Answering the laments for George Floyd in the US this week, Parisians chanted the name of Adama Traoré, a citizen of Malian descent who died in police custody in 2016.

But it can be a thankless task. In my experience, drawing connections, continuities and contrasts between the racisms on either side of the Atlantic invites something between rebuke and confusion from many white European liberals. Few will deny the existence of racism in their own countries, but they insist on trying to force an admission that it "is better `here than there'" - as though we should be happy with the racism we have.

When I left the US in 2015, after 12 years as a correspondent living in Chicago and New York, I was constantly asked whether I was leaving because of the racism. "Racism operates differently in Britain and America," I'd reply. "If I was trying to escape racism, why would I go back to Hackney?" But racism is worse in America than here, they'd insist.

"Racism's bad everywhere," has always been my retort. "There really is no `better' kind."

But it can be a thankless task. In my experience, drawing connections, continuities and contrasts between the racisms on either side of the Atlantic invites something between rebuke and confusion from many white European liberals. Few will deny the existence of racism in their own countries, but they insist on trying to force an admission that it “is better ‘here than there’” – as though we should be happy with the racism we have.

When I left the US in 2015, after 12 years as a correspondent living in Chicago and New York, I was constantly asked whether I was leaving because of the racism. “Racism operates differently in Britain and America,” I’d reply. “If I was trying to escape racism, why would I go back to Hackney?” But racism is worse in America than here, they’d insist.

“Racism’s bad everywhere,” has always been my retort. “There really is no ‘better’ kind.”

[Gary Younge is a British author, journalist, and broadcaster. An editor-at-large for The Guardian and columnist for The Nation, he is also a professor of sociology at Manchester University. Among his five books are No Place Like Home: A Black Briton’s Journey Through the American South (2002), Stranger in a Strange Land: Encounters in the Disunited States (2006), and, most recently, Another Day in the Death of America: A Chronicle of Ten Short Lives (2016). (June 2020)

Follow Gary Younge on Twitter: @garyyounge.]

Spread the word