As Ashley Manning considered striking at the grocery store where she had worked for a decade, the dozens of moments that had pushed her to that point flooded back.

She vividly recalled the indignities she endured throughout the pandemic, starting with child care. When schools shut down, no one could watch her 12-year-old daughter. She wouldn’t allow her elderly grandmother, Ruby, to do it, fearing she would get sick. And her store, a Ralphs in San Pedro, California, where she is the manager of the floral department, refused to work with her schedule, she said.

No one can cover you, she said they told her. Your contract is for six days a week; we need you six days a week.

By then, Manning’s grandmother had started caring for her daughter – they were out of options, schools were still closed and Manning had no leave left to take. So when one of them got COVID-19 in summer 2021 – they still aren’t sure who got it first – Manning’s entire family got sick. Manning was hospitalized for two days, her mother for two weeks and her grandmother for three weeks. Her daughter got sick, too.

On Aug. 13, Manning’s grandmother died alone in the intensive care unit at a hospital in Los Angeles, two days before Manning’s birthday. No family or friends were able to see her before she passed.

“Until this day, it could be my fault that she’s not here,” Manning said. “I look at it that way because I was the one who was working at the grocery store.”

Manning still carried that wound with her when she considered striking against Kroger, Ralphs’ parent company. The stress of her grandmother’s death and everything that came before it led Manning to take short-term disability from work for five months. When she returned early this year, negotiations between the union that represents her and 47,000 workers at several other Kroger-owned grocery stores in Southern and Central California were beginning to deteriorate. Their contract was up and both parties were far apart in the negotiations, which included demands for raises to account for cost of living and inflation increases over the past three years.

Kroger’s first offer: A 60 cent hourly raise.

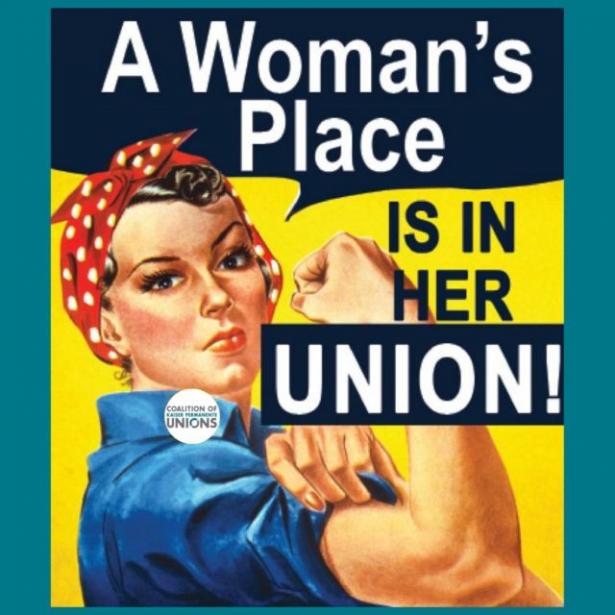

By late March, 95% of workers who voted agreed to authorize a strike, Manning among them. Most of those workers were women, many of them women of color or single mothers like Manning, who were entering into the fight with their employer fueled by two years of turmoil that hit them – and, critically, their families – the hardest.

Over the course of the pandemic, the vast majority of essential workers were women. The vast majority of those who lost their jobs in the pandemic were women. The vast majority of those who faced unstable care situations for their children and their loved ones were women.

And now the vast majority of those organizing their workplaces are women.

Kroger workers are part of a surge in organizing led by women, women of color and low-wage workers impelled by this once-in-a-century pandemic. Many said they feel the pandemic has unmasked the hypocrisy of some employers – they were “essential” workers until their employers stopped offering protections on the job, good pay and commensurate benefits.

Among them, a deep recalibration is happening, dredging up questions about why they work, for whom, and how that work serves them and their families. For many it’s the chance to define the future of work.

“Most women are carrying their families on their backs,” Manning said. “We feel disposable. Everybody is enraged.”

Moments of upheaval become opportunities

Over the past decade, about 60% of newly organizing workers have been women. Women now are also the faces of some of the largest labor movements in years, including the baristas who have unionized over a dozen Starbucks since late 2021, the bakery workers who recently went on strike for four months to secure their first union contract, the call center workers – mostly women of color – who went on strike in Mississippi, and the 17,000 Etsy sellers who went on strike last month to combat transaction fee increases.

All of those movements, most of them happening in companies and even industries for the first time, are ending a disparity that has long existed between men and women in union organization. In 2021, the gender gap in union representation reached its narrowest point since the data started being tracked in the early 1980s by the Bureau of Labor Statistics. About 10.6% of men are members of a union, compared to 9.9% of women; in 1983, the first year data was available, it was 24.7% of men and 14.6% of women. BLS does not collect data on nonbinary people.

For women, unions can be a pathway to equal pay. Studies have found that unionization tends to benefit women more than men, eliminating factors that fuel pay disparity such as secrecy around salaries and societal barriers that discourage women from negotiating pay and benefits.

While union membership has waned in recent decades and was slightly down in 2021 compared to 2020, moments of upheaval have in the past turned into opportunities for women to organize. Take the suffrage movement and the Triangle Shirtwaist fire that killed 146 largely young immigrant women in New York in 1911, the wave of women entering the workforce during and after World War II, and the women’s liberation movement in the late 1960s and ‘70s that helped women join the workforce en masse. Each of those moments changed the course of women’s involvement in the workforce, helping to pass the 19th Amendment, increase union membership and pass equal pay legislation.

The pandemic, which set off the first women’s recession, might be that next catalyst, said Jennifer Sherer, the senior state policy coordinator at the Economic Policy Institute, a progressive think tank.

“It feels like we are living through potentially another one of those moments, where the public and media are awake at a different level right now because of the activity in multiple sectors,” Sherer said.

The shift happening now comes along with a critical change in leadership at the nation’s major unions. After the death of former AFL-CIO president and prominent national union leader Richard Trumka in 2021, longtime labor leader Liz Shuler took over as president – marking the first time a woman took the helm of the largest and most powerful federation of labor unions in the country.

“As work is changing, as the workforce is changing, we are going to be changing with it,” Shuler told The 19th. “Coming out of COVID-19, work is looking differently. That’s why the labor movement is so sorely needed: to show workers that they have a voice and a place in that change.”

The pandemic was a conduit, she said: It allowed women workers to bring up issues that had long plagued them – caregiving, family, health – that had long been treated as niche topics.

“This has been building for a long time, and the pandemic really brought to the surface all of the issues that women have been fighting for and advocating for, for a long time,” Shuler said.

Mary Kay Henry, who in 2010 became the first woman to head the Service Employees International Union (SEIU) – the second-largest industry union after the Education Association of the United States – said this moment feels like a turning point. It gets at the very core of the role women play in communities, families and the workplace.

“Women leaders in the worksite and of organizations like mine are leading a fundamental reorganization of power that isn’t just about our workplace but is about our communities. And for us, it’s reflected in the demand to be respected, protected and paid,” said Henry, who still runs SEIU.

Taken in the broader context of the rise of the #MeToo movement, the dismantling of care and the ping ponging value of the essential workforce, the reasons for organizing are more gendered now, said Sarita Gupta, co-author of “The Future We Need: Organizing for Democracy in the Twenty-First Century.”

“In years past, issues like sexual harassment – that’s not in the bargaining agreement,” Gupta said. “How we think about these movements is not to the side of what a worker movement is, but actually integrated into the worker movement.”

Kathy Finn, the secretary-treasurer of the union representing the Kroger workers in California, has been organizing workers long enough to remember when they held what was then the longest grocery store strike in history, a four-and-a-half-month-long ordeal from 2003 to 2004. Then, a grocery store job used to be a career that could support a family, Finn said. Over the past several decades, those jobs have increasingly become part-time positions with lower pay and limited benefits, a result of cost-cutting measures driven by competition, automation and decreased union participation .

Now, many moms – particularly single moms – at grocery stores feel like their employers are actively working against their needs as parents. The majority of the union’s bargaining committee is women for the first time.

“It definitely feels very different right now,” Finn said.

This is partly because low-income workers, mostly women, have more power to speak up about the support they need from employers. When Manning was away from work after her grandmother’s death, the tenor of the phone calls she received from her bosses had changed from when she was sick last year, she said. They couldn’t find anyone qualified to fill her spot.

When are you coming back, she said they’d ask. We know your grandmother took care of your daughter, we can work with your schedule. We can make adjustments, they said.

Manning returned to Ralphs because she didn’t have the option not to, but something snapped into focus for her. Her value, she said, felt conditional.

As she voted to strike, Manning thought of her grandmother, who never once made her question her self-worth. When Manning tried to start her own floral business, it was her grandmother who encouraged her to pursue it, who got a shed built in her backyard to house Manning’s dream.

“I feel like she’s on board with me, this is where you need to be,” Manning said.

A couple weeks after the vote, Manning, who is on the bargaining committee, was able to help secure a historic agreement that increased hours for part-time employers, improved pension benefits and created health and safety councils at each store – most of the demands they had been seeking.

The wage increase won’t be cents. It’ll be $4.25 an hour.

Upswell in organizing had humble start

This reckoning was forged on the shop floor, through conversations between women in workplaces that once didn’t welcome them at all.

In the 1990s, when women’s labor force participation was peaking in the United States – it has stalled since – women were joining industries long dominated by men. Unionization for a lot of women meant organizing to secure basic rights. Sanchioni Butler, who at the time worked at a Ford plant in Carrollton, Texas, recalled the moment when the few women at the auto plant joined together to help improve the conditions of the women’s bathroom so they would have somewhere to sit during breaks or during their menstrual cycles.

“We got improvements by sticking together,” Butler said in “The Future We Need.” “…When we fought for a shower and couch in the women’s bathroom, that was our women’s movement.”

It seemed then like the only way to improve conditions in a vacuum of federal policy. The Paycheck Fairness Act, for example, which aims to close loopholes in pay discrimination laws, was first proposed around the time Butler was fighting for a couch in the women’s bathroom. It still has not passed.

“If we’re trying to strengthen and improve women’s position in the workforce, the idea of allowing and creating platforms for women to be able to negotiate their conditions, both through a union as well as through community-based, worker-led standards boards, for some of these essential sectors – that’s a start,” said Erica Smiley, co-author of “The Future We Need.”

That nascent start has blossomed into more. In 2011, The New York Times ran “Redefining the Union Boss,” a piece about the women, including SEIU’s Henry, who were heading up major unions and rekindling a hope that their leadership could drive a comeback in unionization after years of reduced membership.In the decade since, the number of women represented by a union started rising again, peaking in 2015. And the numbers don’t break out evenly across race. Union membership has been rising steadily for Latinas, the group with the largest gender pay gap in the country, while it’s leveled out or decreased for other groups. Since 2010, the number of Latinas represented by unions has risen by 31%. But by 2021, rates across the board were back near where they were in 2011.

Still, those numbers mask the amount of organization in 2021, which may not be reflected in statistics for several years. It often takes years to negotiate a union contract and get counted under those figures, and the upswell in organizing now is happening in workplaces that are at the very beginning of that process, workplaces that likely spent a part of 2021 disaggregated and diffuse.

“People are having to overcome a set of obstacles in their daily lives like never before. They’ve lost loved ones and haven’t been able to properly bury them or grieve them because of the COVID pandemic,” Henry said. “They are dealing with staffing shortages and lack of health and safety, but are persevering and organizing on a scale that I’ve never seen before.”

Those obstacles have led people to demand responses from companies that actually reach down to the lowest wage workers, not just talk about them, said Gupta, who is also the vice president of U.S. programs at the Ford Foundation.

“These strikes matter because they are just saying, ‘You can’t just talk about [diversity, equity and inclusion] in your corporate boardroom. What are the other ways you are going to support my ability to stay in the labor force?’” Gupta said.

Some employers are hearing that message, said Maria Colacurcio, the CEO of Syndio Systems, a platform that works with more than 200 companies, including 10% of the Fortune 200, to identify racial and gender pay gaps and improve pay bands and benefits for employees.

Those conversations have changed, she said. Three years ago “they were like, ‘I’m just here to reduce my risk of a pay equity class action.’ Now 99% of our customers are looking at some racial comparison. And I really do think it’s because of the pressure that’s come out of this movement from employees around: This isn’t a gender problem. This is workplace equity, without regard to gender, race, ethnicity, disability, age.”

High-profile union drives, like the one led by Starbucks workers, are forcing employers to think more proactively about what they can offer workers beyond higher pay.

“It’s not a flash in the pan – there are also things getting embedded that are going to force it to be long-term,” Colacurcio said. “It’s really difficult to undo once you’ve opened the windows.”

And yet, being a female leader in a movement that has rarely allowed women to lead has dredged up for many why this has taken so long.

Kim Cordova, the first woman president of the United Food and Commercial Workers Local 7 in Colorado, saw it first hand in January 2021 when she faced negotiators on behalf of Kroger, the parent company of 8,000 grocery store employees in Boulder, Parker and the Denver area her union represents. It was her fight in Colorado that set the stage for what the California workers were recently able to do.

But those negotiations were dripping with gendered vitriol.

She was that woman to them.

“It’s tough being a union president, but it’s tougher being a female president,” Cordova said. “You have to speak louder than everybody in the room, you have to earn your respect that way – you have to fight for it. I’m a double whammy: I’m Latina and I’m a female.”

The corporate negotiators went over her head, she said, reaching out to male lawyers instead of her during the negotiations.

“I am the chief spokesperson, I am the negotiator. I had to send a letter saying, ‘You need to send your questions to me,’” Cordova said.

The fight led to a 10-day strike in the January cold, after which workers secured hourly raises as high as $5.99 – unheard of, she said. “We’ve seen raises to the right of the decimal point, cents not dollars.” The new agreement also addressed the two-tier pay structure that led the men who dominated meat departments to earn more than the women in the lower-paid grocery jobs.

Cordova said the movement of the past three years has been “a career-defining moment” for her after 37 years with a union.

It feels fierce enough to last.

“This is our year, this is our time,” Cordova said. “I don’t think they are going anywhere backward.”

Leaning on other women

The Kroger strike in Colorado inspired the workers in California. Many of the problems are the same: stagnant wages, lax health and safety precautions, and people who feel like they have been pushed to the edge of what they can endure.

In Beverly Hills, Pavilions grocery store cashier Christie Sasaki remembers how hard the strikes in 2003 and 2004 were, but it felt last month like there was no option left. She is often doing the job of two or more people. Her wages have maxed out at $22.50 an hour after 32 years at Pavilions. She has nothing saved for retirement and three quarters of her paycheck goes to her rent, a two-bedroom apartment she shares with her teenage daughter and a roommate she took on to help offset the cost.

“I would like one day to have the American dream – to be able to retire,” said Sasaki, 54. “After almost 33 years, I don’t think I can. It brings a tear to my eye because I would like to be able to go on vacation, I would like to go out to eat.”

Her only opportunity, she said, is to get the best contract she can for herself and her colleagues. She spoke directly to Kroger’s representatives about those struggles in meetings earlier this year, surrounded for the first time by the women who have worked with her shoulder to shoulder.

“During the bargaining committee, my entire table,” she said, “is female.”

Spread the word