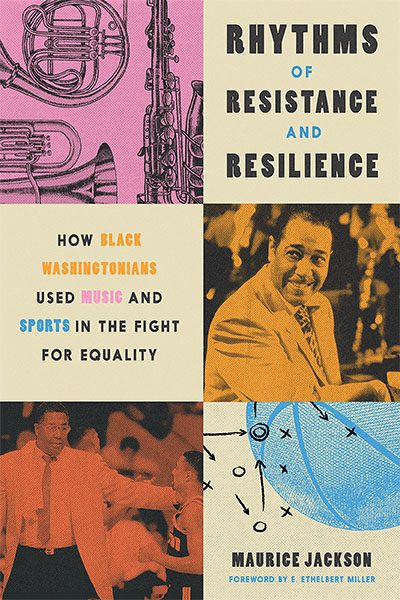

In today’s post, Dr. Robert Greene II, assistant professor of history at Claflin University and President of AAIHS, interviews historian Dr. Maurice Jackson, Associate Professor of History at Georgetown University. Professor Jackson teaches in the History and African American Studies Departments and is Affiliated Professor of Music (Jazz) at Georgetown University. Before coming to academe, he worked as a longshoreman, shipyard rigger, construction worker and community organizer. He is the author of Let This Voice Be Heard: Anthony Benezet, Father of Atlantic Abolitionism, co-editor of African-Americans and the Haitian Revolution, of Quakers and their Allies in the Abolitionist Cause,1754-1808 and DC Jazz: Stories of Jazz Music in Washington, DC. Jackson wrote the liner notes to the 2 jazz CDs by Charlie Haden and Hank Jones, Steal Away: Spirituals, Folks Songs and Hymns and Come Sunday. He has recently lectured in France, Turkey, Italy, Puerto Rico, and Qatar. He served on Georgetown University Slavery Working Group. A 2009 inductee into the Washington, D.C. Hall of Fame he was appointed by the Mayor and the DC Council as Inaugural Chair of the DC Commission on African American Affairs (2013-16) and presented “An Analysis: African American Employment, Population & Housing Trends in Washington, D.C.” to the Mayor and elected leaders of the D.C. government in 2017. His latest book is entitled Rhythms of Resistance and Resilience: How Black Washingtonians Used Music and Sports in the Fight for Equality (Georgetown University Press, 2025).

Robert Greene II (RG): Your new book, Rhythms of Resistance and Resilience, is all about Black Washingtonians. Before we get into the meat of the book, why is the broader history of Black Washington important to both Black American history and Black intellectual history? What is it about the Nation’s capital that has made it such an important city in these broader histories?

Maurice Jackson (MJ): Thank you for speaking with me. I am trained in the history of the Atlantic World of the 17th through 19th centuries. In many ways, the struggles and the strivings of Black people in Washington have been a reflection of the Black struggle in the nation and the world. This history reveals the same mix of structural oppression and inequality with compelling struggles against that oppression and inequality, as can be found in the rest of the United States. Historian Frederic Bancroft wrote in Slave-Trading in the Old South (1931) that “Washington became the center of the slave trade before 1835” and for almost “half a century, the slave-trade, although far from being the largest, was the most notorious.”At the same time, Washington was becoming a national showcase for the selling of Black people, it was also becoming a center of the fight against slavery, locally, nationally, and internationally. By that time, there were at least 130 local abolition societies across the nation, many with Washington connections and many Black and whites worked together. Today, the issue is how can Black people who have built this city be able to stay here in the midst of being priced out? And will a multi-racial coalition come together to halt to economically and racially forced outmigration? Today, Washington is as segregated as it was when President Harry Truman established the President’s Committee on Civil Rights in December 1946. The report entitled To Secure These Rights, ended “he must send his children to the inferior public schools set aside for the Negroes … he must endure the countless daily humiliations brought on by racism and segregation.” That is as true now as then.

RG: Why the use of sport and music? These are traditionally not fields touched on extensively in intellectual history, but your book builds on both of these to create a rich tapestry of life in Washington, D.C. How did sport and music alike provide new avenues for Black people to be activists, community builders, and thinkers?

MJ: Music and sports have come naturally to people of African heritage. Maybe it is so with all the world’s peoples. Yet being natural at something does not naturally make you good at it. You have to put in the time and effort. Take a great musician like John Coltrane. Yes, he was innovative. He could do all kinds of things with notes and phrasings. But he still had to read sheet music and learn the western cannons of music. He thought things out. Just look at his mathematical notations –same with Ornette Coleman or Geri Allen. Take Wynton Marsalis. He is equally adapt in the world of classical music as he is at jazz winning awards in both categories. Coltrane wrote “Alabama” about the 16th Street bombings in Birmingham. Billie Holiday sang “Strange Fruit” to protest lynchings. Charles Mingus wrote “Fables for Faubus.” Ellington wrote “Black, Brown and Beige ” in honor of Black people who fought at the Battle of Savannah and of Henri Christophe who served with the American forces. Black musicians like Washington’s Sweet Honey in the Rock have used their abilities and talents to fight for their people.

There are so many myths in life, in sports, and in music. For example, Black kids can’t shoot—Steph Curry, the Washington areas Kevin Durant have disproved that. So did Elgin Baylor and Dave Bing and who both when went to Spingarn High School. Black people can’t play Quarterback and can’t lead. Two Black quarterbacks led their teams in the Super Bowl. Black folks are only good with big balls like football and basketball and not small balls like golf and tennis but look at Serena and Venus Williams, Coco Gauff, Madison Keys and Naomi Osaka following the lead of Althea Gibson and DC’s own Margaret and Roumania Peters.

Few things have united Black and white people in DC. But, at times, music and sports have united residents. In 1939, contralto Marian Anderson was denied the right to perform at Constitution Hall owned by the Daughters of the American Revolution’s (DAR). The fight extended to the DC School Board when the Marian Anderson Citizens Committee (MACC) tried to reserve Central High School (later renamed Cardozo), which was all white. The New York Amsterdam News of April 8, 1939 denounced the board’s action as “Nazism in D.C.,” where “democracy and justice are flaunted so cruelly” in a city claiming to be the capital of democracy. Howard University professor Doxie Wilkerson of the National Negro Congress led the MACC to challenge the Board’s decision. With the support of First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, who resigned her DAR membership, Secretary of the Interior Harold Ickes arranged for Anderson to perform on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial. In short, Anderson could perform at a site controlled by the federal government, but not in Washington, D.C. On Easter Sunday, April 9, 1939, the concert was held with 75,000 in attendance, one of the largest truly multiracial actions in US history. Anderson sang “Nobody Knows the Trouble I’ve Seen,” and “Gospel Train,” arranged by her friend Harry Burleigh, “Ave Maria,” and “America.” Broadcast over NBC Radio millions, the world, heard it live, in rebroadcasts, in newsreels and movie houses. Ickes ordered the National Park Service to desegregate, including all government-owned parks. While the city would not desegregated its public facilities, the Anderson campaign made the city’s cause a national one and helped pave the way for the desegregation of the Washington in 1957.

RG: Your previous books, such as Let This Voice Be Heard: Anthony Benezet, Father of Atlantic Abolitionism and DC Jazz: Stories of Jazz Music in Washington, D.C. have dealt with different aspects of Black cultural and intellectual life over the last three centuries. How is your newest book situated in this larger narrative of the intersection of Black creativity and intellectual life?

MJ: Anthony Benezet was a schoolteacher—a French born Huguenot (Protestant) whose family was persecuted and exiled from Catholic France. He saw the oppression of enslaved Africans in Philadelphia through the eyes of his own oppression. He meant to do something and opened the African Free School where Robert Allen and Absalom Jones studied. Benezet studied the enlightenment thinkers especially the Scottish Moral Philosophers —George Wallace, Frances Hutcheson and later Adam Smith. He joined that with a profound study of Africa. So, I studied everything that Benezet studied and wrote Let This Voice be Heard. I coedited Quakers and Their Allies in the Abolitionist Cause, 1754-1808 with Susan Kozel. My own graduate school advisor Marcus Rediker later wrote a book and produced a play on the Quaker Benjamin Lay. I co-edited with Jacqueline Bacon African American and the Haitian Revolution. Since then Leslie Alexander and Brandon Byrd have published notable books on the topic.

From an intellectual history view, Black scholars and thinkers were always in the forefront, along with regular working people to fight for racial, social and economic equality in DC, the nation and the world, especially the Caribbean and Africa. Washington’s Mary Church Terrell proclaimed on February 18, 1898 before the National American Women’s Suffrage, “And so, lifting as we climb, onward and upward we go, struggling and striving, and hoping that the buds and blossoms of our desires will burst into glorious fruition ere long.” Anna Julia Cooper published Slavery and the French and Haitian Revolution and played leadership roles in W.E.B. Du Bois’ Pan-African movement. Nannie Helen Burroughs founded the National Training School for Women and Girls in 1909. Alain Locke the foundational thinker behind the “New Negro” concept was at Howard University. A Washington Renaissance, was proclaimed even before a Harlem Renaissance as expressed by Edward Christopher Williams in his When Washington Was in Vogue. Carter G . Woodson, “the father of Black History “was here founding the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History and the Journal of Negro History and Negro History Day, now Black History Month. In Washington, W. Alphaeus Hunton and Leo Hansberry researched and taught about Africa at Howard University. My wife Laura and I just visited the Elizabeth Catlett exhibit at the Brooklyn Museum. A 1934 graduate of DC prestigious Dunbar High School and later Howard University, her work helped inspire the Black Arts Movement that had its foundation in WDC going back to when my late friend Amira Barak was a student at Howard and studied with Sterling Brown. I could go on for days.

RG: Much of your scholarly work has intersected with public work on behalf of the D.C. government. How do you see your role as a scholar and writer in a city like Washington, D.C.? Do you see yourself as part of a longer lineage of Black scholars and concerned citizens in the nation’s capital?

MJ: Under President Woodrow Wilson, African-American federal employees saw an increasingly hostile and segregated atmosphere as they sought the same job and housing opportunities as whites. After World War I, the “Red Summer” riots saw white mobs kill more than 100 Blacks in 25 U.S. cities, including D.C. where at least three whites, including two policemen and four Black men were killed and hundreds injured. One hundred years later, we again see attacks on federal workers. Washington became the first major city in the U.S. with a Black majority population by 1957. Eleven years later, in 1968, the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. prompted widespread protest and rioting as underlying factors such as job and housing discrimination and police brutality contributed to a spontaneous display of frustration.

By 1970, the Black population was 70%. Today, Washington is undergoing a “renaissance” of redevelopment, with gleaming office buildings and expensive apartments, but the benefits have not gone equally to everyone.

The Mayor of Washington appointed me as the inaugural chair (2013 2017) of the DC Commission on African American Affairs to study the problem and offer ideas toward a solution. Today, housing costs, fewer job opportunities, crime, and poor inner-city schools have driven the Black population to below 45 percent. And with the loss of the Black population a lot of the city’s Black history and culture is in danger of being lost. My latest manuscript, which ought to be out within a year is titled Halfway to Freedom: The Struggles and Strivings of Black Folk in Washington, DC, 1780 to 2020. It tells the long social history of a people, a national and even global history through the eyes of Black people in the nation’s capital. I have put my heart and soul into the book just as I have put my heart and soul into this city.

RG: In conclusion, what was most surprising about what you discovered while researching your latest book?

MJ: A Russian thinker once wrote, “you can’t swim the same river twice.” It means you have to keep up with the currents—to adjust to the conditions; to keep moving; and to try to grow as best you can. I do not know if it is a surprise or a further affirmation of the boundless capacity of Black people to endure and to fight for equality; to learn along a continuing journey; to seek the truth; and to use that truth to better humanity. That is what Paul Robeson, Du Bois, Angela Davis and others have taught us. That is what Amiri Baraka taught as he studied the Turkish author Nazim Hikmet, the Haitian poet Jacques Romain, the Chilean Pablo Neruda, the Irishman Sean O’Casey. Of course, he knew the works of Georgia Douglass Johnson, Nikki Giovani, Sonia Sanchez and Gwendolyn Brooks, of Langston Hughes, James Baldwin, Chinua Achebe, Wole Soyinka and Nadine Gordimer. Black scholars have learned as Tony Morrison said of Dr.King: “to look beyond ourselves.” Blair Ruble and I enlisted top jazz scholars in the city to edit a volume DC Jazz: Stories of Jazz in Washington, DC. The pianist and composer Jason Moran wrote the forward. I wanted to look deeper and wrote Rhythms of Resistance. It reaffirmed my belief that music and sports teaches us —to seek to grow individual and collectively. “To look beyond ourselves.” Always.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.

Spread the word